반골의 기하학: 메리 헤일만

Geometry in Rebellion: Mary Heilmann

02

Text by 존 야우 John Yau

Translation by 박상미 Mimi Park

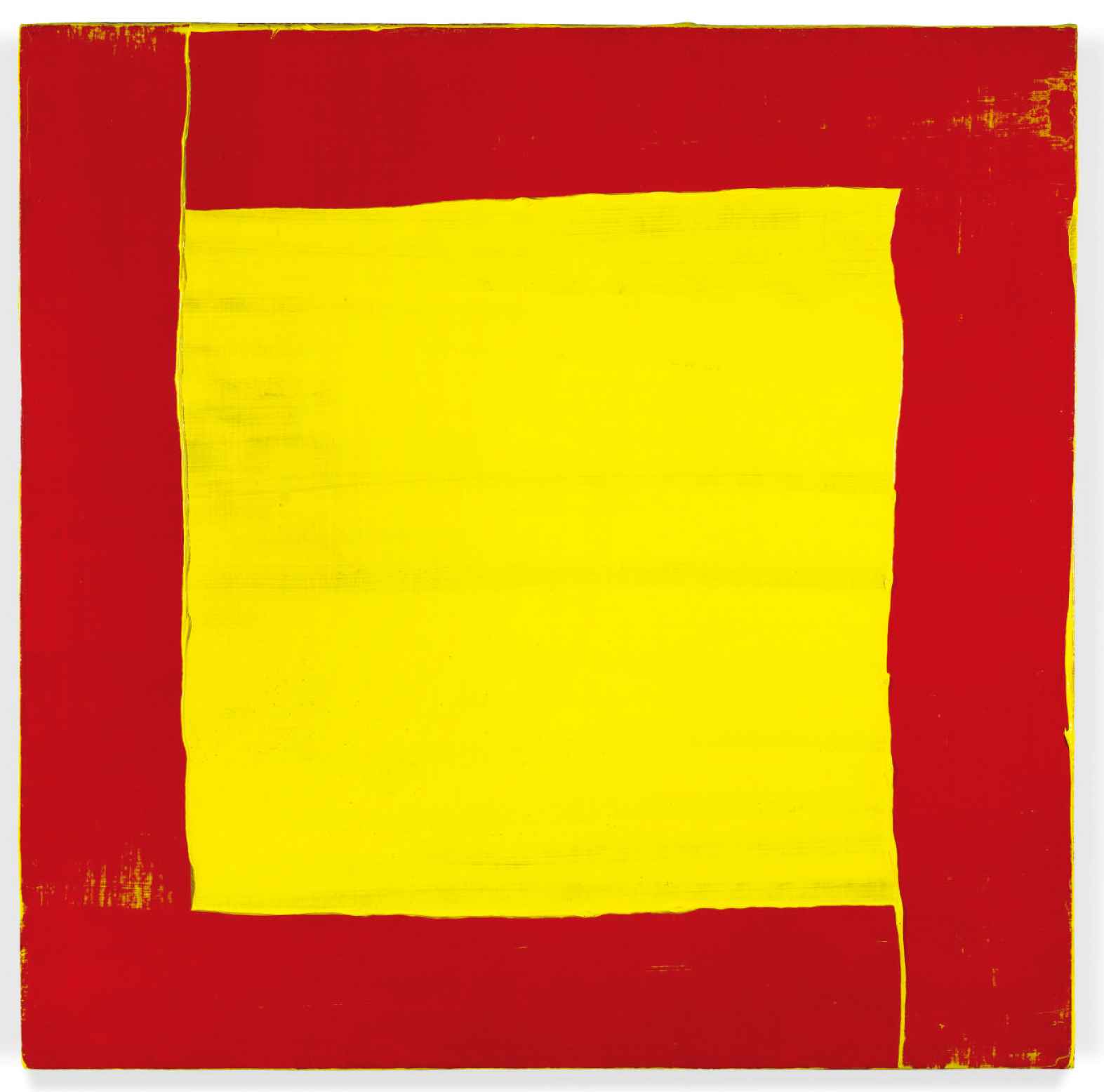

불규칙하게 생긴 빨강 사각형 띠는 중앙에 역시 불규칙한 노랑 사각형을 감싸고 있다. 잘 보면, 헤일만이 두 개의 색으로 세 개의 불규칙한 사각형을 그렸다는 사실을 알 수 있다. 이 그림에서 시도한 것들은 다음 그림에 영향을 준다. 이 그림들은 서툴고 투박한 데 그게 이들의 강점이다. 이들은 예의바르게 선 안에 머무르지 않는다. 그녀는 기하학의 융통성 없음과 순수함—적어도 케네스 놀란드와 프랭크 스텔라가 그들의 작업에서 보여준—을 허물고 그녀 자신과 다른 사람들이 꼭 그렇지 않아도 된다는 것을, 고분고분하지 않아도 된다는 가능성을 열어놓았다.

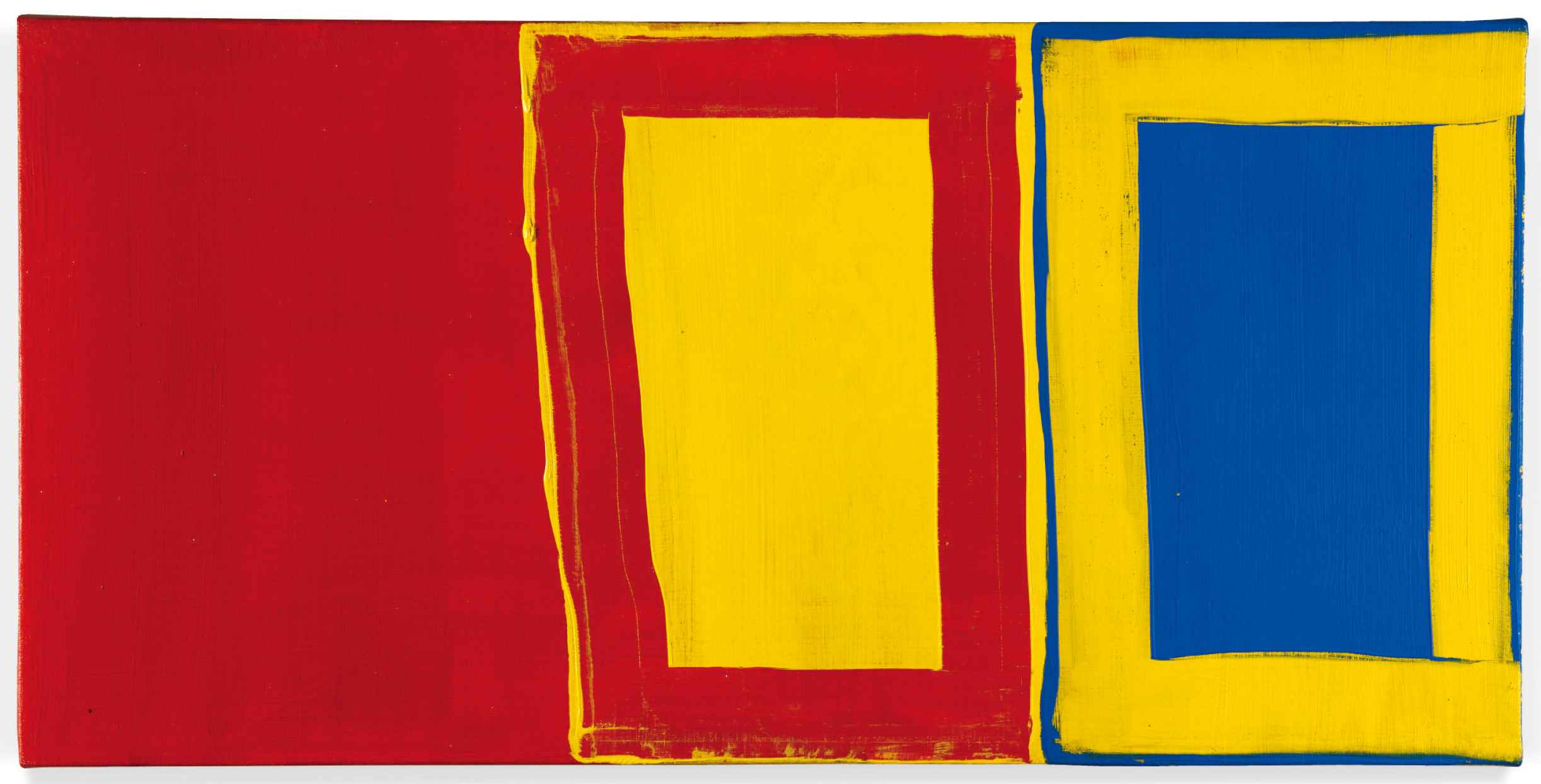

<두 개를 위한 첫번째 셋: 빨강, 노랑, 파랑(1975)>에서 헤일만은 두 개의 넙적한 사각형을, 아이들의 블럭쌓기처럼, 수직의 사각형 안에 아래 위로 쌓았다. 아래 사각형의 바탕색은 파랑색이고 위 절반은 노랑색이다. 헤일만은 스퀴지로 노랑 사각형 띠를 파랑색 바탕 위에 모서리까지 닿게 그려서 똑바르지 않은 노랑색 틀을 그려넣었다.

그녀는 위쪽의 노랑색 바탕에서 똑같은 과정을 반복하는데, 이번에는 빨강색 사각형 띠를 그린다. 바탕색을 바꾸면서, 그리고 짝수의 사각형을 홀수의 색으로 그려서 기하학 추상 회화에 깔린 하나의 가설—모든 것은 부드럽게 맞아 떨어져야 한다는—에 도전한다. 그보다 더한 가설인 이상적인 회화, 즉 완벽한 형태라는 게 있다는 것인데, 헤일만 그림에는 이 두 가설 모두 존재하지 않는다.

헤일만은 기하학의 경직성을 허무는 동시에, 개인적인 내용의 제목을 사용하면서 표현적인 가능성을 더했다. <소용돌이(노먼에게)(1977)> 에서 그녀는 넙적하고 구불거리는 빨강 띠를 그림의 네 모서리에 평행하게 그렸다. 노란 바탕색이 그 사이로 보인다. 작가의 손놀림이 명백하지만 붓자국은 보이지 않는다. 이 그림이 쉽게, 막 그린 것처럼 보일 수 있지만 실제로 그렇지 않다. 여기서 분명한 것은 인습에 대한 헤일만의 철저한 공격이다. 막 그린 것 같은 그녀의 방법론은 선배 작가들의 작업을 경직되어 보이게 한다. 그녀는 그림 속에 감정을 표현함으로써 그 전시대 추상작가들이 얼마나 깐깐했었는지를 보여준다.

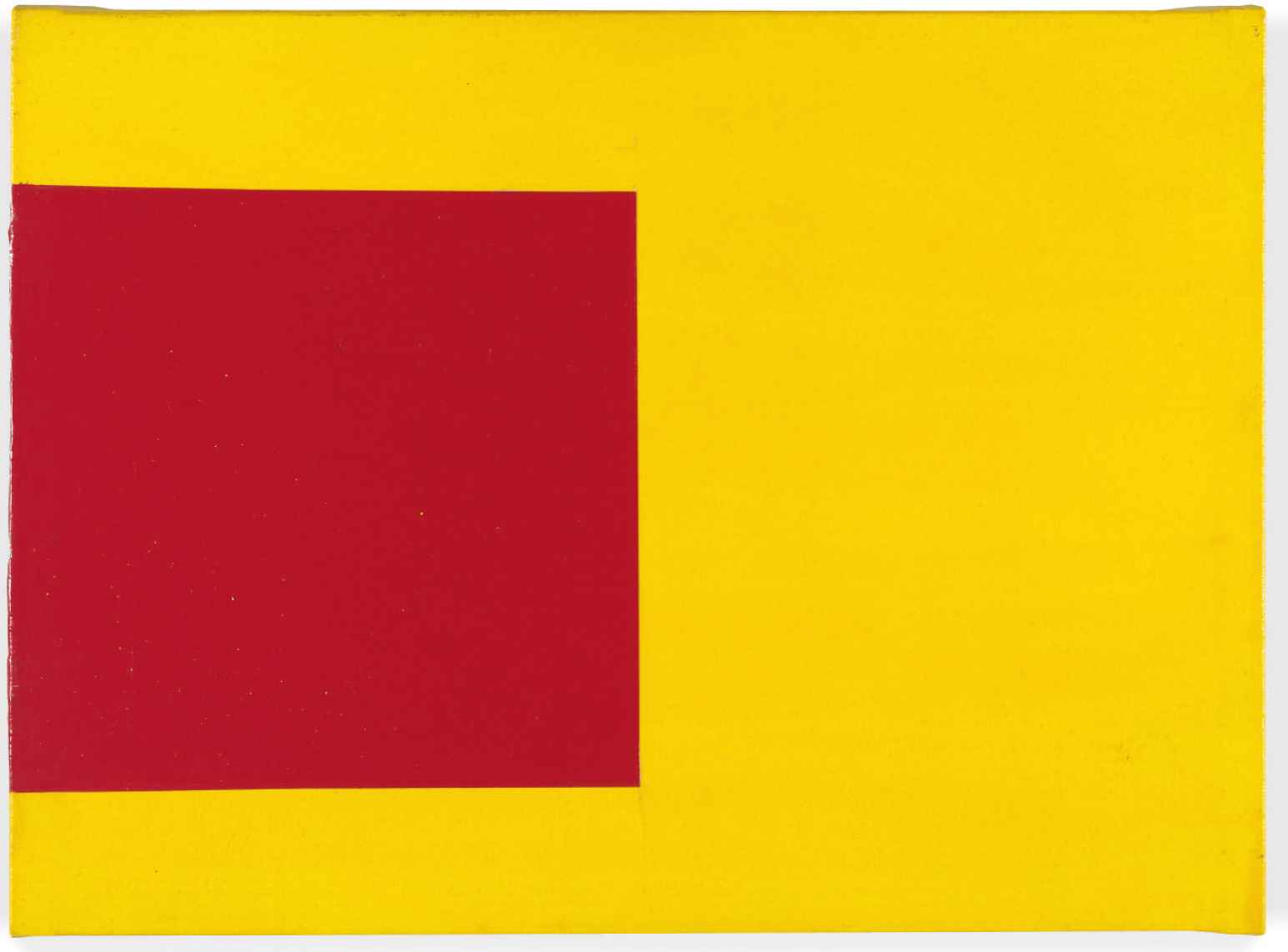

이 전시에는 포함되지 않은 <끝 (1978)>은 빨간색 정사각형이 수평으로 긴, 큰 사각형 위에 왼쪽 화면 끝까지 맞닿아 끝나는 그림이다. 빨간 정사각형을 왼쪽 끝으로 치우치게 하면서 사각형이 가지는 안정성을 약화시키고 동시에 형태와 내용 간에 긴장감을 유발한다. 노란 바탕 위에 떨어진 빨간색 물감은, 마치 정사각형의 순수함에서 새어나온 피나 눈물처럼, 기하학은 질서정연해야 한다는 고정관념에 저항한다. 이 그림의 제목은 무엇이 끝인지 구체적으로 말해주지 않지만 헤일만이 사각형의 안정성을 깨뜨리고 우연히 떨어진 빨간 물감을 그냥 둔 것은 무언가 끝났다는 것을 암시하고, 이는 다시 고립감을 준다. 마치 슬픔에 잠겼지만 나눌 수 없는 것처럼.

이 초기작들을 보면 헤일만이 이 평범한 형태들을 어떻게 사용하고 배치하는가에 따라, 또 색의 사용에 따라 어떤 감정들을 표현할 수 있는지 보려고 했던 것을 느낄 수 있다. 그녀는 차근차근 더 나아갔다. 이러한 회화적 지능이 그녀의 초기의 “반골 기질”을 발전시킬 수 있었다. 또는 크릴리가 레버토브에 대해서 말한 것처럼 그녀의 “열정적이고 재미난 마음이 완고한 의지가 되기로 한 것이다.”

역시 초기작이고 관련된 작품인 <사각형을 밀다 #1>에서는 그림 정면에는 떨어진 물감 자국이 없고 왼쪽 표면에만 있다. 이는 매우 다른 느낌을 낳는다. 한가지는 헤일만이 중앙이 아니라 왼쪽 끝에 칠한 빨간 사각형은 조세프 알버스에서 케네스 놀란드까지 중앙이 있는 형태(v자 형태, 과녘, 또는 정사각형)에 대한 논평 같이 느껴진다. 사각형을 왼쪽 끝에 위치시킨 것은 또한 움직임을 암시한다. 그림과 그 형태는 안정되지도, 안전하지도 않다. 이들은 변화가 불가피한 영역에 위치해있는 것이다. 커다란 빨간색 물감은 스퀴지를 사용한 과정의 산물이고, 작가가 지우지 않고 남겨둔 선택의 산물이다.

윌리엄 버틀러 예이츠가 “무너진다, 중심이 흔들린다. 무질서가 세상에 퍼졌다.”라며 역사 속 혼란의 순간을 날카롭게 통찰한 것처럼 헤일만의 그림도 그런 가능성을 전달하고 있다. 그녀의 그림은 그 상태를 그린다기 보다 그 가능성을 암시한다. 그녀의 초기작에서 절제와 표현은 서로를 붙잡고 있다. 또, 헤일만이 재료를 다루는 기술이 점점 원숙해지면서 완벽함에 저항하는 의지 또한 강해진다. 그녀의 기술적인 원숙함은 언제나 더 큰 목표를 위한 것이고, 그녀가 하는 모든 것은 필요에서 나온 것이다.

<유령 사각형(1976)>에서 그녀는 모든 것이 그림의 표면 위에 있어야 한다는 사실에 도전한다. 그녀는 노란색 바탕 위에 기울어진 파란 정사각형을 중앙에서 약간 비껴간 곳에 위치시키면서 이 일을 한다. 사각형의 오른쪽 절반을 차지하는, 동시에 파란 정사각형을 약간 가리는 조그맣고 반쯤 투명한 노란색 사각형을 그려넣어서 그림을 비대칭으로 반을 나눈다. 두번째 노란 사각형은 그림의 오른쪽 절반을 차지한다. 이 반투명의 노란색을 통해 밑에 깔려있는 파란 정사각형의 유령을 볼 수 있다. 동시에 이 두번째 사각형 위에 그녀는 꽉 찬 파란색 정사각형을 그려넣었다. 이 두 개의 사각형은 함께 겹이 있는 공간을 만들어낸다.

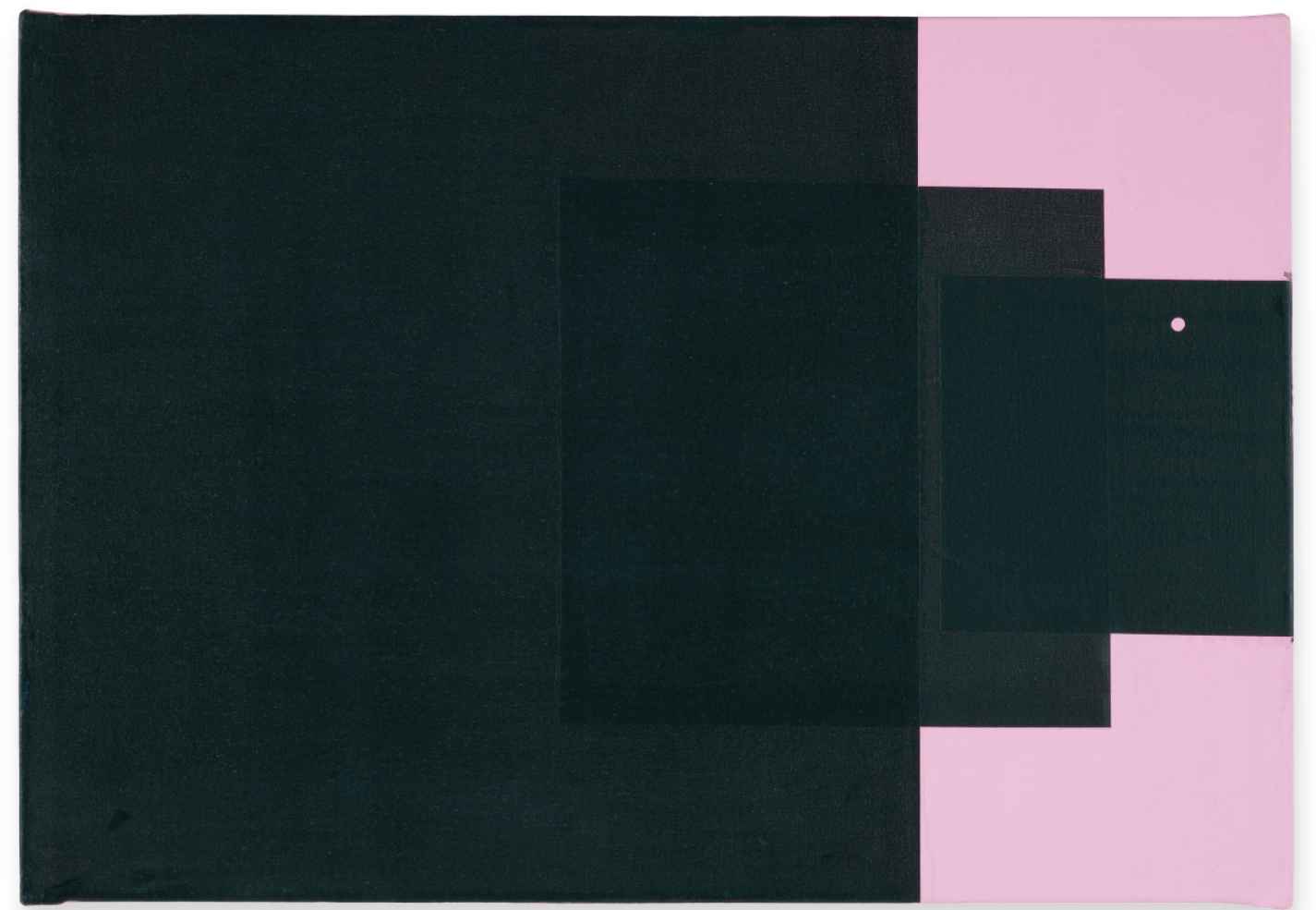

돌이켜보면 1974년과 1979년 사이 그녀가 그린 적, 황, 청색의 그림들이 기하학적 추상과 미니멀리즘과 연관된 형식적인 전통에 도전하고 있었던 것이 분명하다. 우리는 그녀가 대형 기하학적 추상 회화로 대표되는 경직된 남성성을 일견 캐주얼하게 보이는 여성성으로 맞섰다고 할 수 있을 것이다. 1979년에 와서는 그녀가 회화에 표현하던 감정을 <황홀감> <마지막 춤을 나와 함께>와 같은 작업을 통해 확장시킨다. 그녀는 여기서 사랑과 아픔의 노래들을 연상시키는 분홍과 검정색을 사용하기 시작한다. 그 이전 작품들이 증명하는 것은 그녀가 한 번 그림을 그리기 시작하면 하늘 아래 뭔가 새롭고 지속되는 것을 만들기 위한 그녀의 야망과 맹렬하게 씨름하고 있다는 것이다.

In The First Small Red, Yellow, Blue (1975), which is twice as long as it is tall, Heilman fills the painting with three uneven rectangles. In this painting, which anticipates her later use of multiple panels, the ground changes from red to yellow to blue. The first rectangle is a solid red, whose right edge is ragged, turning it into an awkward monochrome abutting a ragged yellow rectangle, demarcated by an imperfect red band made with four squeegee strokes.

The irregular red band, defining the middle of the painting, encloses most of an irregular yellow rectangle. The yellow extending beyond the red bands suggests that each of the three uneven rectangles is made of two colors, even if that is not immediately apparent. With the irregular red band, the vertical band on the left aligns with the red rectangle’s slanting, ragged right edge. Everything Heilman does in the painting effects what she does next. The paintings are gauche and blunt, which is their strength. They are not trying to be polite and stay within the lines. She has undone geometry’s inflexibility and purity – at least as Kenneth Noland and Frank Stella manifest them in their celebrated paintings – clearing a space for herself and others in which unruliness can manifest itself.

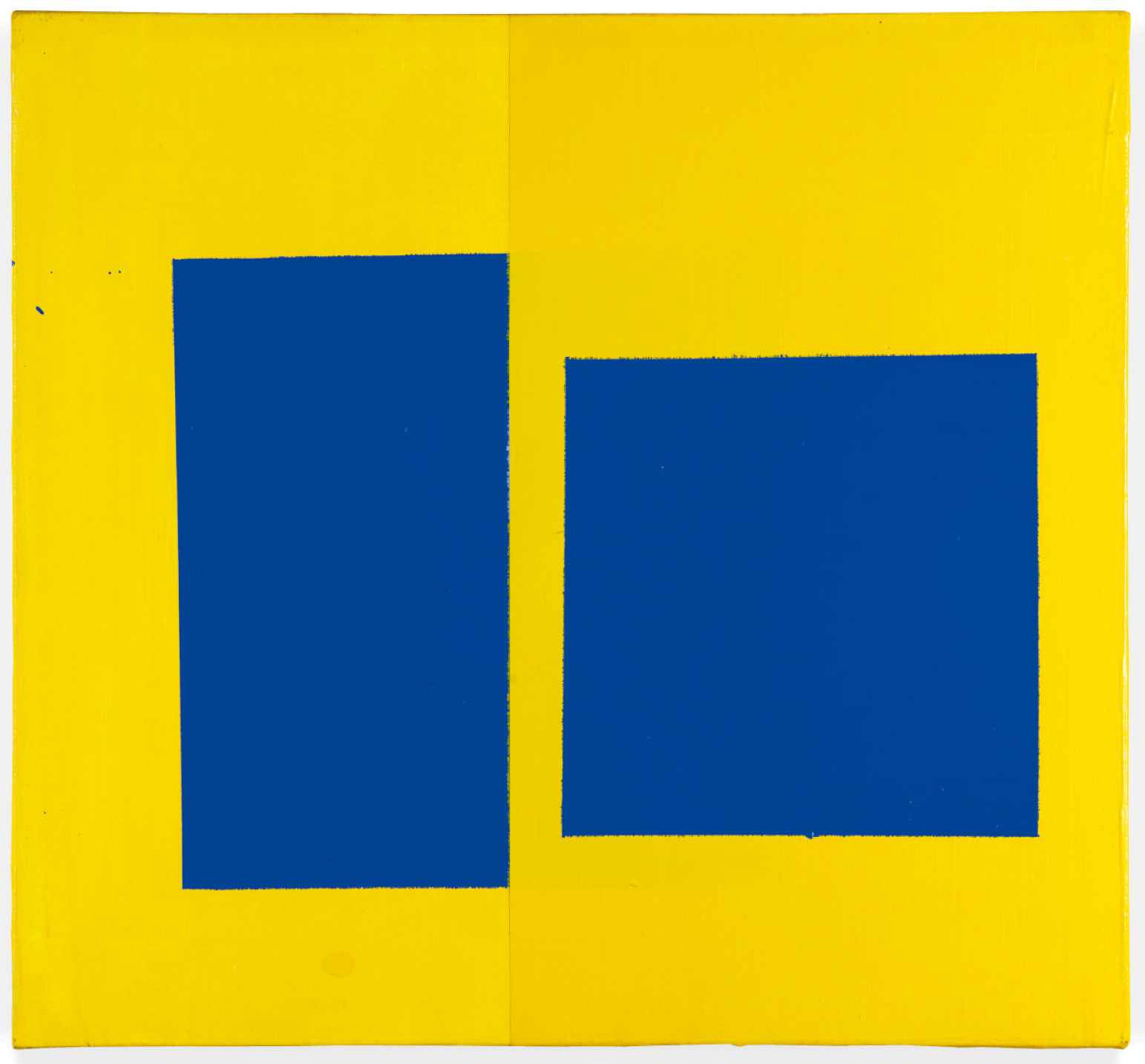

In 1st Three for Two: Red, Yellow, Blue (1975), Heilmann stacks two horizontal rectangles on top of each other, like children’s building blocks, within a vertical rectangle. The ground of the bottom half is blue, while the top half is yellow. The artist has used a squeegee to lay down a yellow band that conforms to the painting’s outer edges against the bottom blue ground, creating an uneven yellow frame within the blue rectangle.

She echoes the process on the upper yellow ground, but this time with a red band. By changing the ground, which peeks through the two colored bands, and by using an odd number of colors within an even number of rectangles, she exposes one of the assumptions behind much geometric abstraction: it is all supposed to fit smoothly together. The deeper assumption is that an ideal painting — a perfect form — is ultimately achievable. Heilmann is having none of this.

As she went about undoing geometry’s rigidity, she also began adding expressive content, at first in her use of personal titles. In The Spiral (for Norman) (1977), she makes the wide, wobbly, red band running parallel to the painting’s four edges out of two Ls, with the yellow ground visible in the space between them. The artist’s hand is evident, but it is not holding a brush. While the painting may come off as casual and even offhand – as do the others from this period – clearly this is not the case. Rather, what is evident is the thoroughness of Heilmann’s assault on dominant conventions. If anything, the apparent offhandedness of Heilmann’s approach makes the work of older painters look stiff. By exposing her feelings, as she begins to do in these paintings, she reveals how uptight the abstract artists of an earlier generation were.

In The End (1978), which is not in this exhibition, a large horizontal rectangle is commanded by a red square that terminates at the painting’s left edge. By placing the red square on the far left, she undermines the rectangle’s stability while activating the tension between form and container. Red drips on the yellow ground beneath the red square are defiant presences that disrupt geometry’s association with orderliness — blood or tears leaking from the purity of the square. Without ever specifying what, according to her title, has come to an end, Heilmann’s destabilization of the rectangle and aleatory use of red suggest the cessation of something, which in turn evokes a sense of isolation, as if you are in grief but cannot share it.

One senses in these early paintings Heilmann recognized that she wanted to see how much feeling she could inject into her painting through her use and placement of generic forms, and the colors she would make them. In order to move forward, she proceeded methodically. I think this aspect of her painterly intelligence is what informs her early “contrariness.” Or, as Creeley, speaking about Levertov said – and certainly this passage is especially applicable to Heilmann – her “passionate, whimsical heart committed to an adamantly determined mind.”

In an earlier, related painting, Sliding Square #1 (1978), there are no drips on the work’s face, but there is on the left side, resulting in a work with a very different feeling. For one thing, the red square, which Heilmann has painted on the far left instead of the center, becomes a commentary on the centered forms (chevron, target, or square) employed by many older artists, from Josef Albers to Kenneth Noland. The placement on the far left also suggests movement – that painting and its forms are neither stable nor secure; they constitute an arena where change is inevitable. The large red drips on the side are the residue of a process using a squeegee, which the artist chooses to leave, rather than remove or cover over.

Heilmann’s painting conveys the likelihood that, as William Butler Yeats astutely observed at another chaotic moment in history: “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.” Heilmann’s painting hints at that possibility, rather than trying to picture it. In this and other early paintings, restraint and expression hold each other together. At the same time, you see Heilmann’s growing mastery of her materials as well as her willingness to reject perfection. One thing about her growing mastery is that it is always at the service of a definable goal, that everything she does comes out of necessity.

In The Ghost Square (1976), she challenges the insistence that everything has to be on the painting’s surface. She does this making a yellow ground in which doesn’t quite center a lopsided blue square within the rectangle. Over the right half of the rectangle, and partially cover the blue square, she paints a smaller, semi-transparent yellow rectangle, essentially dividing the painting into two unequal halves. The second yellow rectangle covers the painting’s right half. Through its porous yellow ground you can see the ghost of the blue square embedded in the first layer. At the same time, within this second rectangle she has painted a solid blue square. Together, the two rectangles, one of which is partly semi-transparent, create a layered space.

In retrospect, it is clear that in the red, yellow, and blue paintings she did between 1974 and ’79, she was challenging formal conventions associated with geometric abstraction and minimalism. One could say that she confronted the rigid masculinity of large-scale geometric abstractions with a seemingly casual femininity. By 1979, she would expand upon these feelings in paintings such as Enchantment and Save the Last Dance for Me (both 1979), when she began using pink and black to conjure up proms and rock ‘n roll songs of love and heartbreak. What the paintings that preceded them prove is that once Heilmann took up painting, she was able to come to terms with the ferocity of her ambition to make something new and enduring under the sun.

RELATED POSTS