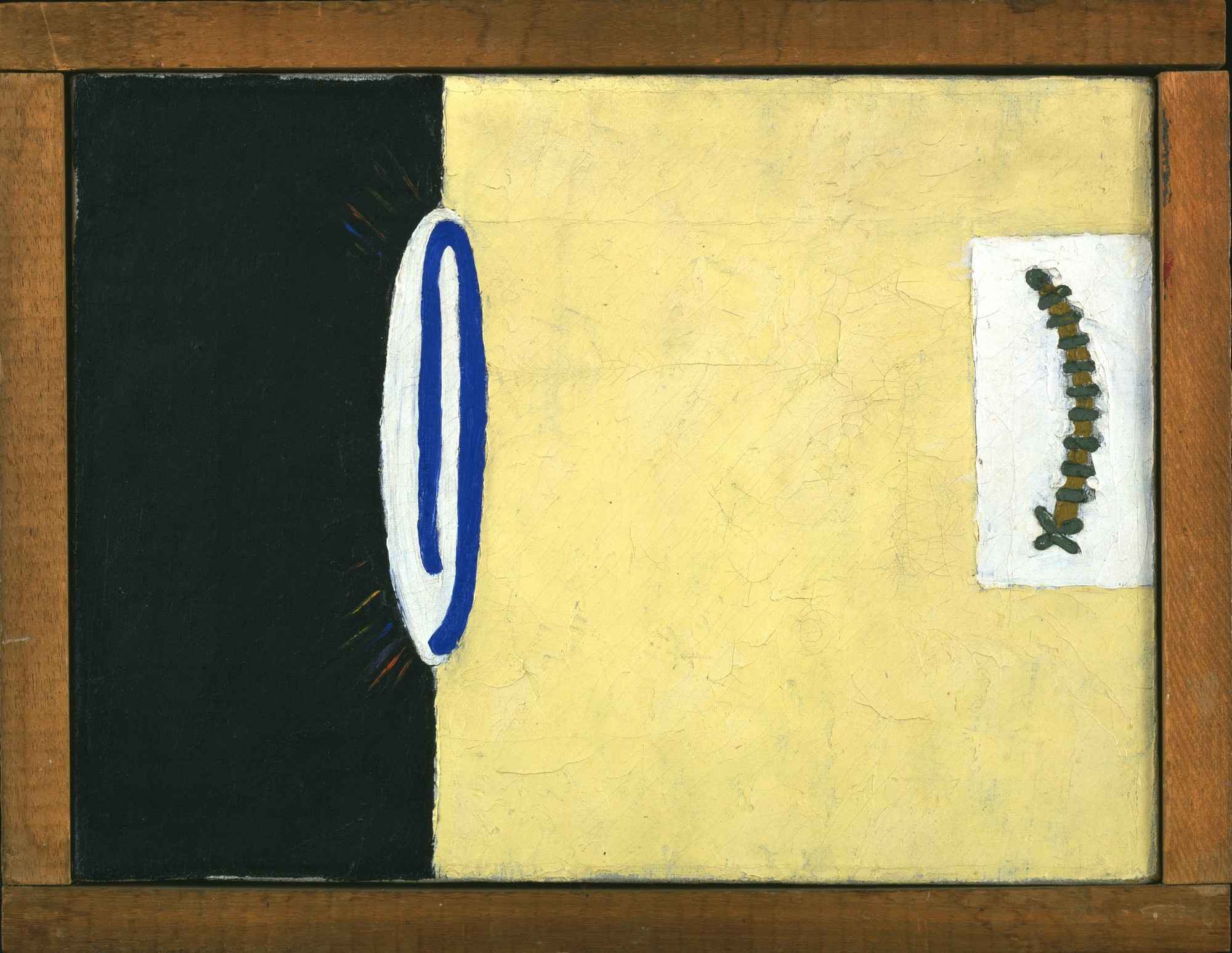

눈을 감고 보다: 포레스트 베스

In the Eye of the Solitariness: Forrest Bess

Text by 존 야우 John Yau

Translation by 박상미 Mimi Park

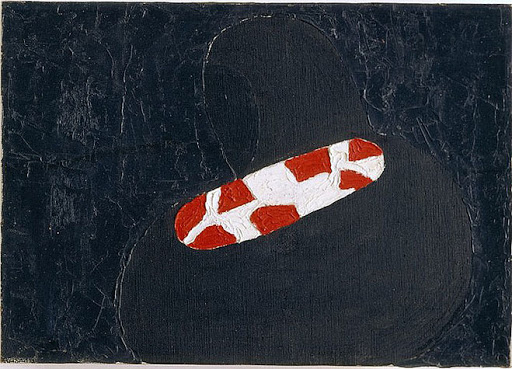

![MA-BESSF-00083-image-2 Forrest Bess, Untitled, ii. [purple], 1952](https://clumsy.site/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/MA-BESSF-00083-image-2.jpeg)

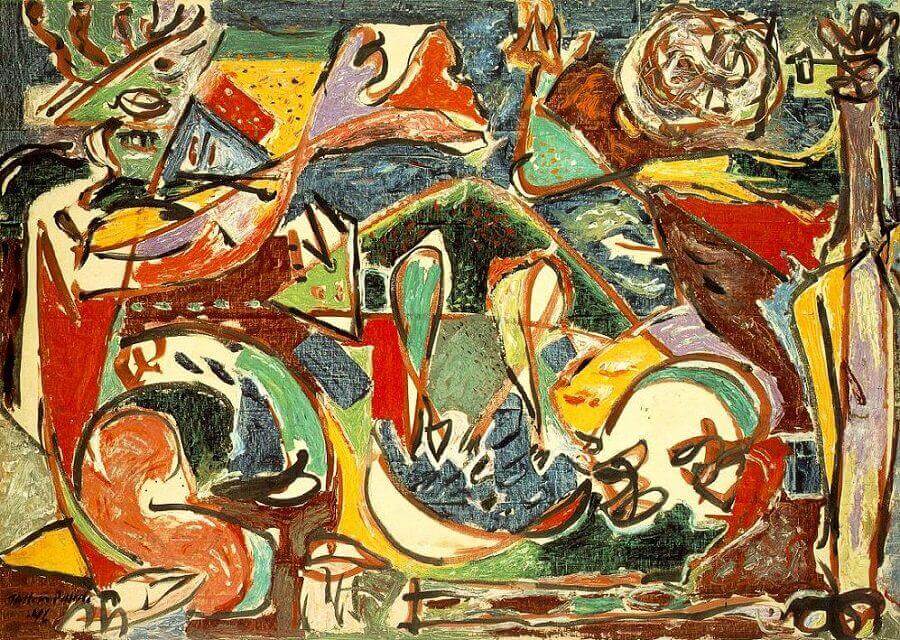

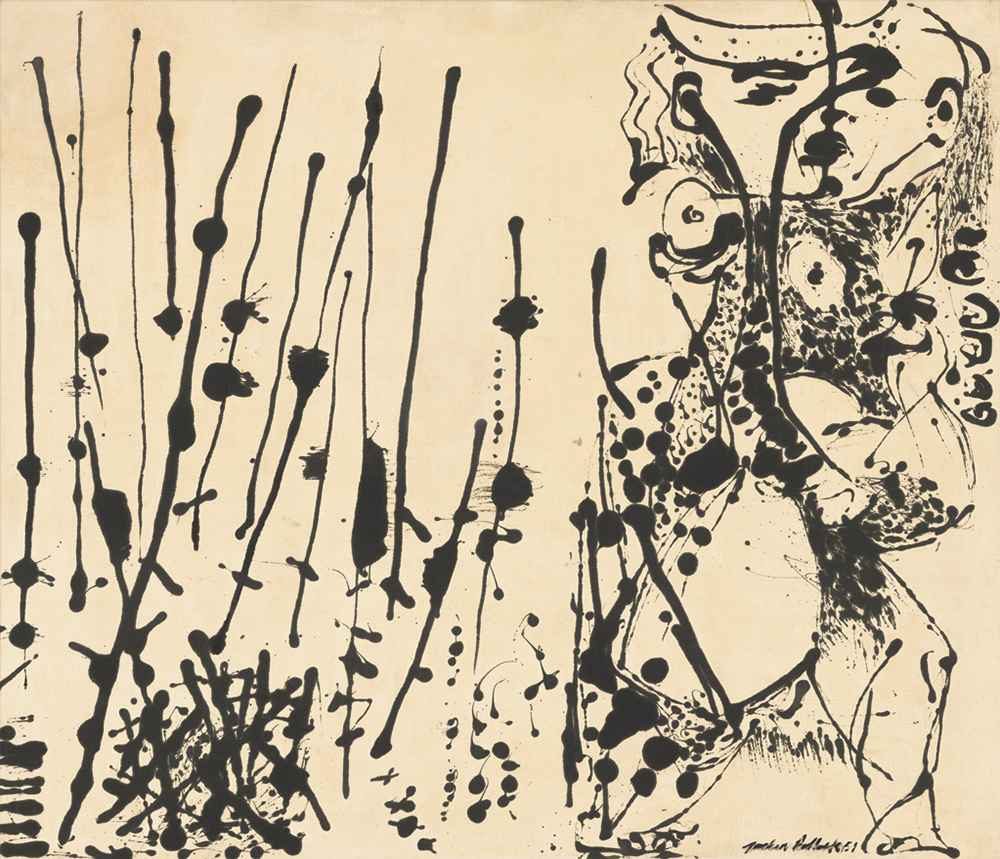

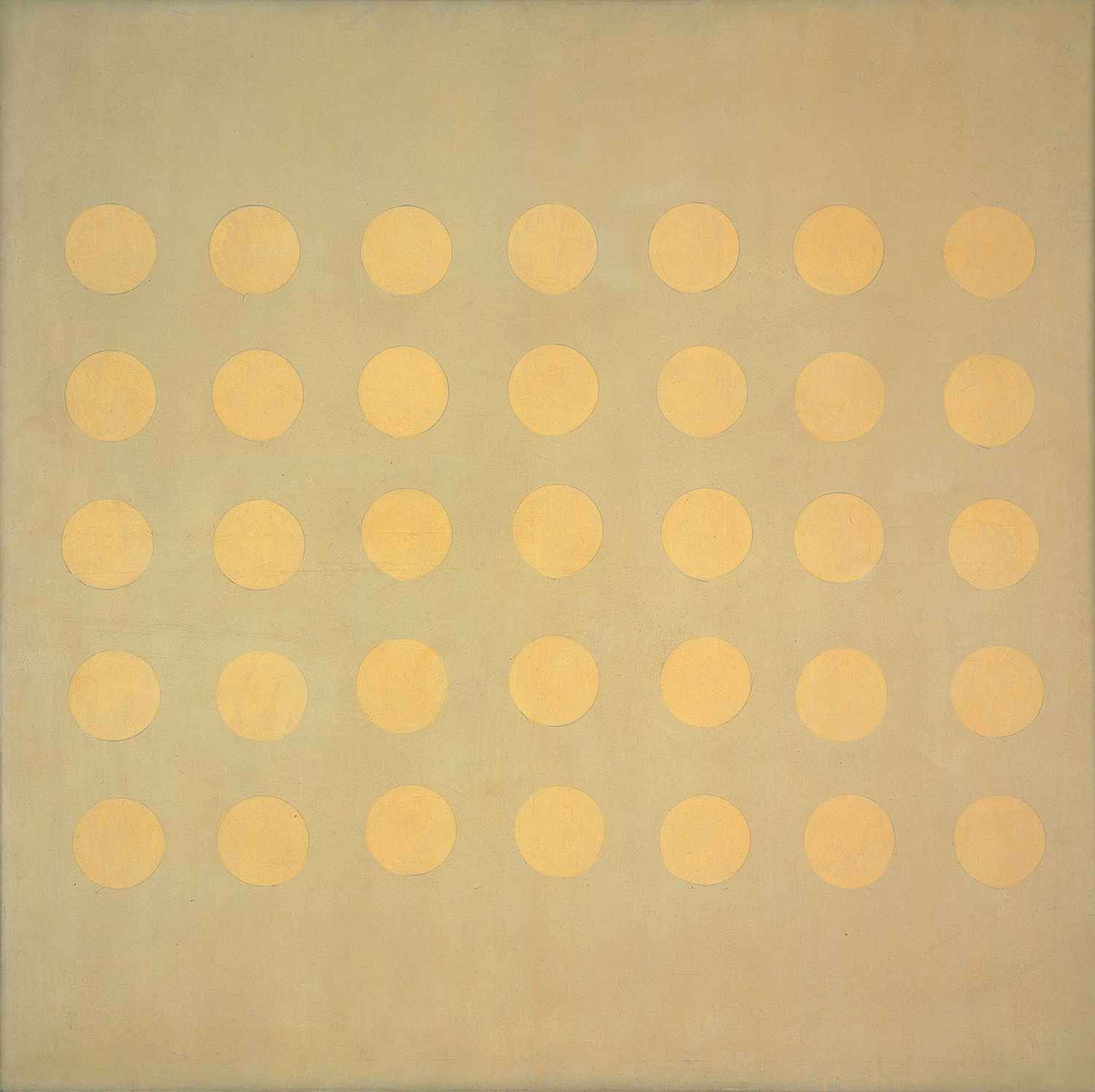

Bess, it should be noted, wasn’t the only one to go against the grain during the 1950s and ’60s. Charles Seliger (1926-2009), the youngest of the Abstract Expressionists, Myron Stout (1908-1987), and Mark Tobey (1890-1976) also worked on an intimate scale. By the mid-60s at the height of Pop Art and Minimalism – Bess’ work more or less dropped out of sight. He wasn’t mentioned in textbooks and one was not likely to see his work included in surveys of Abstract Expressionism because he wasn’t part of the group. He was, as should now be clear, a loner, an isolato, someone who felt best when he was cut off from society. In some sense, he turned his back to the world, but in some other way he did not. As his letters to Shapiro and others attest to, Bess was desperate to be understood and accepted.

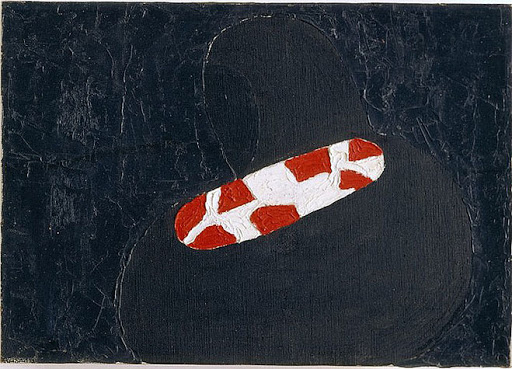

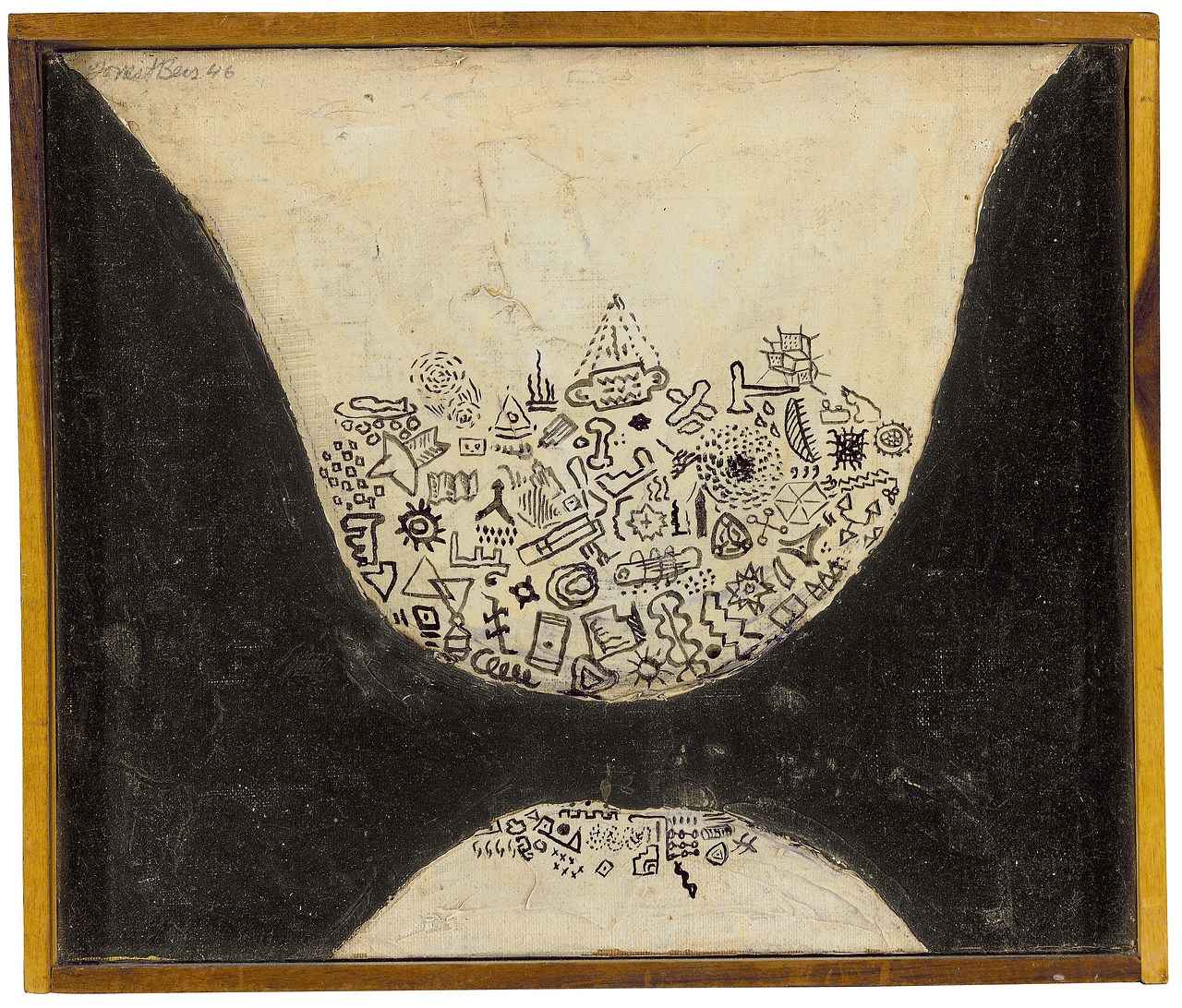

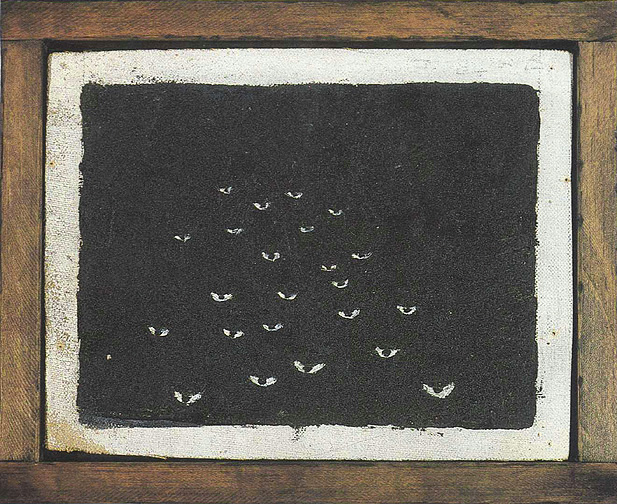

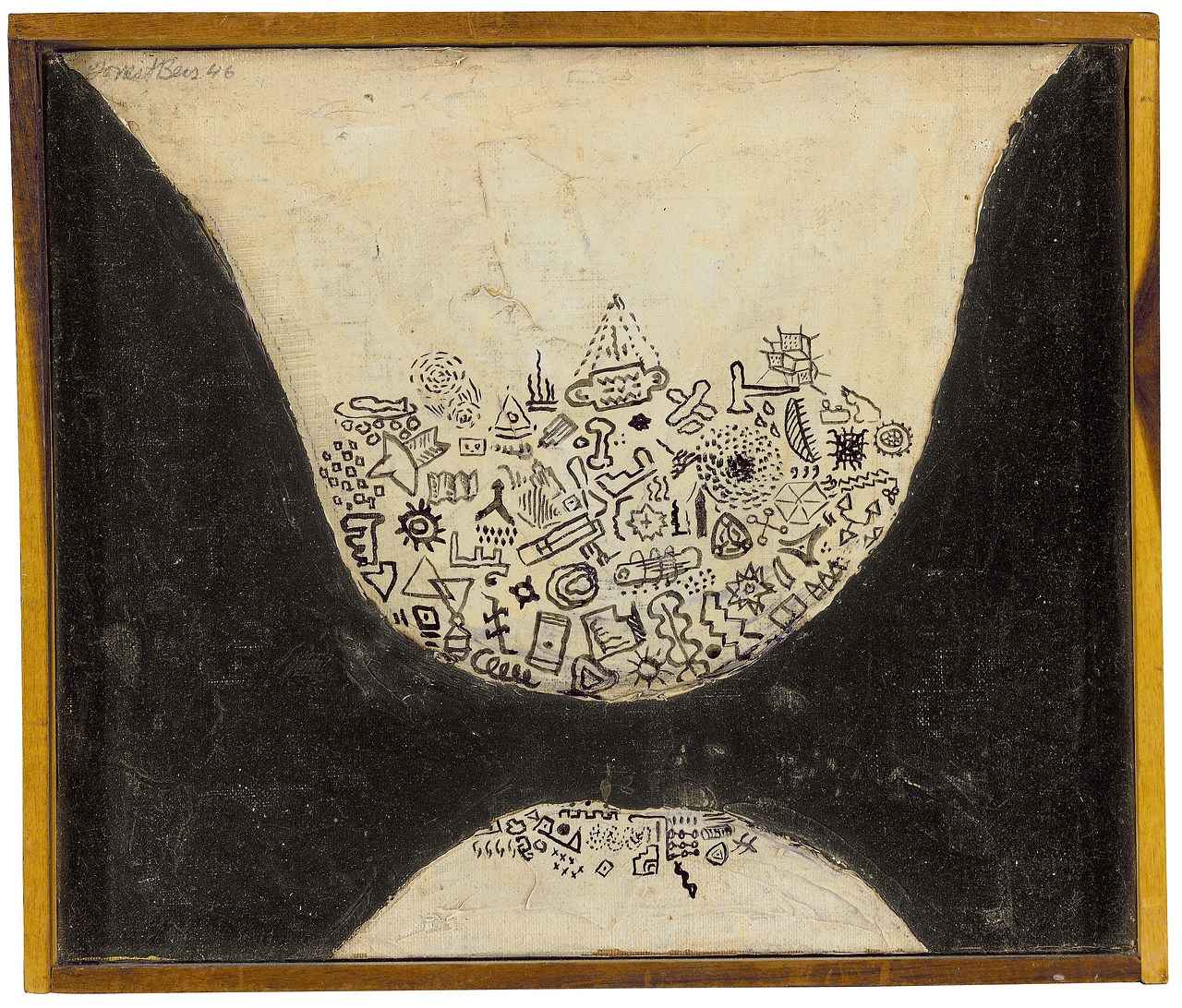

In 1981, Bess was reintroduced to the art world by way of a small one-person exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Barbara Haskell organized the show and there was a small pamphlet available for free. According to the pamphlet, the symbols in Bess’ work were based on “obscure sexual references” and there was something “lurid” about them.

Bess (1911-1977) has been dead for almost 34 and a half years. And so his inclusion in a show where the majority or the work was completed between 2010 and 2012 comprise a de facto institutional recognition of his influence on contemporary art (an influence that a generation or two of painters have already taken for granted).

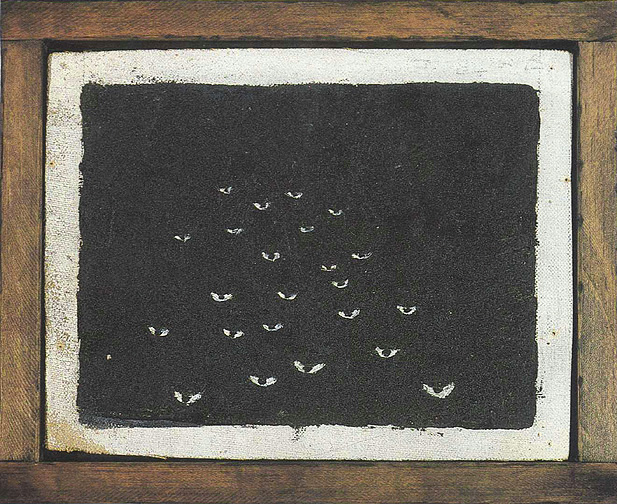

What comes through with exceptional clarity – and what saves Bess’s simple shapes and curious array of personal symbols from mere eccentricity-is the clammy-palmed necessity simmering just beneath each painting’s skin. Bess made art like his life depended on it, because it did. The same can be said for James Castle, Adolf Wölfli or Martin Ramirez. It’ what is outside about outsider art. Throughout the image conjured by Bess, Castle and the others, you can all but feel their frontal lobes throbbing, ready to explode.

RELATED POSTS