충격에 관하여

On Shock

Text by 김지호 Jiho Kim

Translation by 송효정 Irene Song

파쿠르는 달리기, 점프, 균형잡기, 매달리기, 올라가기, 기어가기 등 인간 고유의 움직임을 이용해 장애물을 극복하며 움직이는 이동예술(L’art du deplacement)이다. 1980년대 말 프랑스의 9명의 청소년들에 의해 시작되었다. 파쿠르(Parkour)라는 말은 ‘’길, 코스, 여정’이라는 의미를 지닌 불어 ‘parcours’에서 왔는데 한자로 표현하면 ‘道’와 같다.

2004년부터 꾸준히 파쿠르를 수련해온 나는 파쿠르가 현존하는 모든 스포츠 중 특이하게도 신체에 가해지는 충격을 일상적으로 받아들일 뿐 아니라, 충격을 스스로 추구한다는 점에서 이에 관한 생각들을 다각도에서 나누어보고 싶다. 국립국어원 표준국어대사전에 의하면 충격의 사전적 정의는 다음과 같다.

- 물체에 급격히 가해지는 힘.

- 슬픈 일이나 뜻밖의 사건 따위로 마음에 받은 심한 자극이나 영향.

- 사람의 마음에 심한 자극으로 흥분을 일으키는 일.

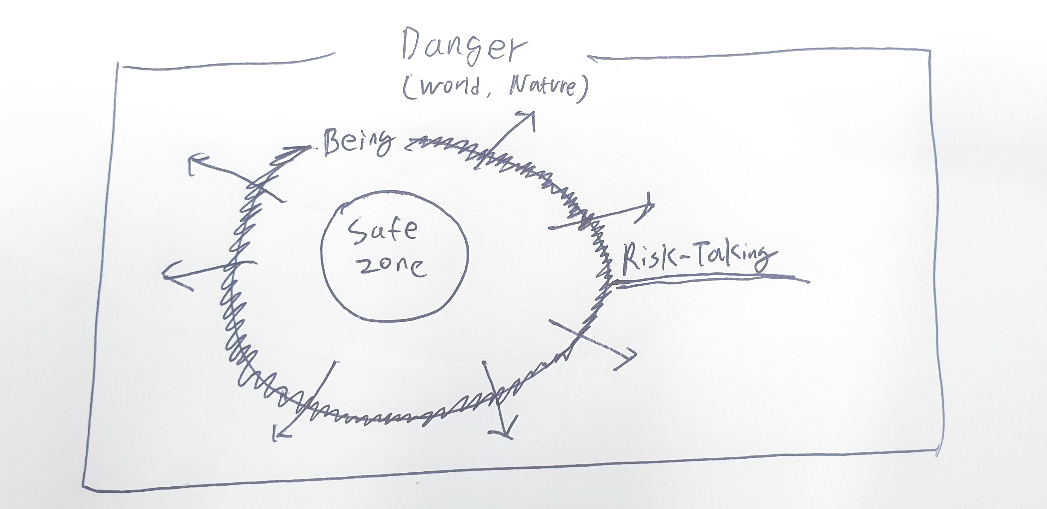

사전적으로 ‘충격’의 의미는 물리적인 측면과 함께 정신적, 심리적 차원까지 포함하고 있다. 충격은 시각, 청각, 촉지각(통각), 미각, 후각 등의 감각기관을 통해서 경험한다는 점에서 ‘충격’은 신체성을 띈 언어라 하겠다. 신체성을 띈다는 의미는 철학의 주요 논점 중 하나인 주체(존재)와 객체(세계) 사이의 관계에 대해 사유해 볼 수 있다는 뜻이다. 연속된 위험의 세계에 던져진 존재는 충격으로 말미암아 ‘고통’을 경험한다. 이러한 주체와 객체 사이의 관계를 다음과 같이 파악해 볼 수 있다.

헬렌 켈러는 ‘안전은 대개 미신이다’라고 했다. 객체(세계)는 근본적으로 위험(Danger)의 연속이다. 우리가 인지하고 있는 ‘안전’은 실재하지 않으며 오직 관념 속에 있을 뿐이다. 안전하지 안않은 상태, 즉 위험이라는 것은 크게 두가지로 나눌 수 있는데, 주체(존재)가 수용할 수 있는 위험(Risk)과 수용할 수 없는 위험(Danger)이 그것이다.

데인저(Danger)는 인간이 통제할 수 없는 천재지변, 통제가 불가능한 위험의 영역이다. 자연의 본질은 코로나처럼 인간이 예상할 수 없는 위험의 영역들, 그런 사건으로 이루어져 있다. 리스크(Risk)는 반대로 인간이 통제할 수 있고 예측할 수 있는 세계의 영역이다. 예를 들어 암벽 등반은 떨어질 것을 대비해서 하네스와 로프를 활용한다. 그래서 인간이 통제하는 위험(Risk)이 된다. 이렇게 예측 가능한 위험을 통제하는 것을 리스크 테이킹(risk-taking: 위험 감수)이라 한다. 많은 사람들이 파쿠르를 목숨 건 데인저 테이킹(Danger-taking)으로 오해하지만, 실제 파쿠르는 신체뿐만 아니라 정신적으로 리스크와 데인저 사이의 모호한 경계를 오간다. 이를 통해서 자신의 생존의 질과 양을 확장시킨다는 점에서 파쿠르는 위험 감수 훈련이다.

사실 우리가 안전 혹은 평화라 부르는 것은 리스크라는 수용 가능한 위험의 영역 안에서만 느낄 수 있는 것이다. 잘 생각해보면 안전하다고 느끼는 것들은 그만큼 익숙한 위험을 내포하고 있다. 반대로 데인저(Danger) 영역에는 익숙하지 않은 것, 이질적인 것, 모호한 것, 알 수 없는 것들이 지배하고 있다. 위험 감수 훈련은 점점 자신이 감수할 수 있는 위험의 영역을 확장해 나감으로써 실제 위험(Danger)한 상황에 직면했을 때 그것을 극복해낼 수 있는 생존능력을 기르는 것이다. 반대로 자신의 일상에서 끊임없이 위험을 회피하거나 제거하려는 태도는 실제 위험(Danger)이 왔을 때 아무것도 할 수 없는 무기력함을 낳게 된다. 안전이라는 실재하지 않는 상상 속 관념에 갇혀 위험을 피하면 피할수록, 실제로는 더 큰 위험이 찾아오는 것이다.

파쿠르를 가르치다 보면 안전장치가 있는지 확인한 후 파쿠르에 참여하겠다는 사람들 (어른, 학부모 등) 을 자주 만난다. 역설적이게도 이런 환경은 사람들의 예상과는 다르게 더 많은 부상을 초래한다. 특히 초보자가 매트, 발판, 스폰지로 가득 차 있는 환경에서 훈련을 하게 되면, 자연스럽게 ‘이곳은 안전하기 때문에 아무거나 시도해도 된다’라고 생각하게 되어 뇌의 위험 감지 시스템을 사용하지 않게 된다. 인간은 자신의 ‘안전’을 제3자에게 위임하거나 책임을 전가할 때, 자신의 능력과 주변 환경을 고려하지 않고 스스로의 한계점을 뛰어넘어 무모한 행동을 한다. 사고나 부상의 발생을 방지하려면 우리가 스스로 할 수 있는 것이 무엇이고, 어떠한 상황에서 필요한 것이 무엇인지, 그리고 그 상황에서 주어진 위험을 감당할 수 있는지를 아는 것이 중요하다.

이러한 위험 감수의 원리를 바탕으로 ‘충격’을 바라보면 자발적으로 충격을 추구하는 것이야말로 의도치 않은 충격으로부터 자신을 지킬 수 있는 능동적인 결정이라 할 수 있다. 그렇다면 구체적으로 어떻게 자발적인 충격 감수성을 기를 수 있을까? 나는 긍정적인 변화를 위해서는 지덕체보다도 체덕지로 인지하는 사고방식이 더 효과적이라는 것을 수년간의 코칭과 실제 훈련 경험을 통해 알게 되었다. 즉, 몸으로 충격을 통제하는 방법을 배워야 정신도 충격으로부터 회복하는 법을 알게 되고, 또 그 이상의 성장까지도 기대할 수 있다는 것이다.

Parkour is a movement art (L’art du deplacement) that utilizes inherent human movements of running, jumping, balancing, hanging, climbing, crawling, and more to overcome obstacles. It was started by nine teenagers in France in the late 1980s. The word “parkour” comes from parcours in French, meaning “road, course, journey”, and in Chinese characters it is the same as ‘tao’ (道).

Having been training parkour since 2004, I would like to share my thoughts on how, in contrast to other sports, it not only consists of routinely accepting impact on the body, but also deliberately pursuing shock. According to the Standard Korean Language Dictionary, the definition of shock is as follows.

- The force applied rapidly to an object.

- A severe stimulus or influence received by a sad or unexpected event.

- A thing that excites one’s mind with intense stimulus.

By the dictionary definition, the meaning of shock includes physical as well as mental and psychological aspects. “Shock” is a physical language in that it is experienced through sensory organs such as sight, hearing, touch, taste, and smell. To acknowledge physicality is to consider one of the main points in philosophy, the relationship between subject (entity) and object (world). An entity that is thrown into a world of constant danger experiences “pain” through shock. The relationship between this subject and object can be identified as follows.

Helen Keller once said, “Security is mostly a superstition.” Objects (world) are essentially a series of dangers. The “safety” we perceive is not real, and exists merely in our imagination. This state of non-safety, risk can be divided into two different kinds; “risk” that can be taken by the subject, and “danger” that cannot be accepted by the subject (entity).

“Danger” is a natural disaster area, a hazard zone that people have no control over. Nature consists of dangerous phenomena, such as the coronavirus, that are unforeseen by humans. On the contrary, “risk” is a part of the world that humans can control and predict. For example, rock climbing uses harnesses and ropes in case of falls. Thus it becomes a risk that humans can regulate. In this way, to take control over dangers that can be predicted is called “risk-taking”. Many people misunderstand parkour as “danger-taking”, but in reality parkour moves between risk and danger, physically as well as mentally. Through this, parkour is a risk-taking exercise in that it expands the quality and quantity of one’s survival.

In fact, what we call safety and peace is something that can only be felt in the area of acceptable danger, risk. If we think about it carefully, the things that we feel to be safe pose just as much familiar danger. On the contrary, the unfamiliar, different, ambiguous and known dominate in the area of danger. Risk-taking training is to train the survival ability to overcome real danger, by steadily expanding the areas of risk that one can handle. Conversely, constant avoidance or attempts to remove risks in ones daily life results in idleness, of being unable to do anything in the face of real danger. The more one avoids danger by being trapped in the unrealistic, false notion of safety, the greater the danger that comes.

As I teach parkour, I often meet people (adults, parents, etc.) who express interest in parkour after checking if there is a safety device. Paradoxically, this kind of environment causes more injuries than people would expect. Particularly, if beginners train in environments full of mats, scaffolds, and sponges, they start to think ‘this place is safe, and therefore I can try anything”, and thus refrain from using the brain’s natural risk detection system. When humans delegate their “safety” to third parties or shift responsibility, they act recklessly beyond their own limitations without considering their abilities and surroundings. To prevent accidents or injuries, it is important to know what we can do on our own, what we need in certain circumstances, and what risks we can afford in those events.

Based on this principle of risk-taking, if we think about the pursuit of “shock”, we can say that it is an active decision to protect oneself from unintended shock. Then how can we develop sensitivity to spontaneous shock? I have learned from years of coaching and real life training experience that for positive change, the mindset of recognizing with the body is more effective than with knowledge. In other words, learning how to control shock with the body will help the mind recover from shock, and even further growth can be expected.

The safety and effectiveness of parkour’s fall and landing techniques, which protect the body from shock, have already been proven by a number of studies abroad. In 2013, the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine published the article “Ground reaction forces and loading rates associated with parkour and traditional drop landing techniques.” Ten male parkour trainees with an average of 2.9 years of parkour experience were invited to perform parkour landing techniques (using only the heels), and the traditional landing method (front of the feet first), five times each. The amount of impact was measured in the following three areas.

- mVF(Maximum Verticle Force): maximum vertical impact total over weight

- tmVF(Time to mVF): time it takes to reach the maximum vertical impact as soon as the feet touches the ground.

- LR(Loading Rate): speed at which shock is transmitted to the body

The results were astounding. Parkour landing has less shock on the body, and is safer than traditional landing methods.

So how much difference is there in the shock regulation ability of parkour trainees vs the average person?

Let’s take a look at the 2015 SCI study, “A Comparison of the Habitual Landing Strategies from Differing Drop Heights of Parkour Practitioners (Traceurs) and Recreationally Trained Individuals”. Ten parkour trainees around the age of 22 with an average of 4.9 years of experience, and ten sports club members around the age of 24 with an average of 8.6 years of athletic experience were compared in their landing (three times each) from an elevation that is 25% and 50% of their heights. The results showed a noticeable difference of up to two or three times the amount in all areas, including mVF, tmVF, and LR.

For ordinary people who encounter parkour through SNS and media, it may appear as a sport that is destructive to the joints, but research data reveals the opposite. It is not a coincidence that parkour has the most safe landing techniques out of all existing sports. In an urban environment full of rough concrete, exposure to high shock is inevitable in order to implement constant movement using only the bare hands and body, and many trials and errors have helped us devise high-quality landing techniques. If you train parkour the right way, rather than hurting the joints, the “shock” strengthens bone density and connective tissue. This principle is called the “anti-fragile”.

“Anti-fragile” was first conceptualized by Nassim Nicholas Taleb at the Tandon School in New York University. Self-resilience, which is widely implemented in society, means to be able to recover from the impact of physical and mental damage, restored to the same state as before the shock. However, “anti-fragile” means to develop into a better stage, rather than returning to the prior state. Elite parkour athletes possess impressive movements beyond human limitations, as well as a resilient mentality that controls fear and adapts flexibly to difficult environments, because it adheres to this principle of the “anti-fragile”.

Han Byungchul’s “The Palliative Society: Pain Today” warns us how dangerous individuals and society are, those who have forgotten the meaning and value of pain as a result of modern discourse around its ‘meaninglessness”. Modern people’s attempts to achieve happiness without pain end up frustrated and trapped in a lackluster daily life. To pursue a life without pain is to move in the direction of lifelessness. This is why Oxford evolutionary psychology professor Robin Dunbar, known for “Dunbar’s Number”, believed that in advanced countries where there are no risks of daily life, more extreme sports are being developed. This is because only within a dangerous environment can you build self-trust, and thinking beyond yourself, be able to clearly tell who is your enemy or friend.

In SNS and the digital realm, modern people are disconnected as much as they are connected in that physical “pain” is excluded, and so much as a minor inconvenience can be passed by the wave of a finger on the screen’s feed. Such a digital world’s evasive habits infiltrate reality, and eventually change one’s life. Now, more time is afforded to viewing others’ lives than crafting one’s own. Regarding these generational trends, French-born American novelist Anaïs Nin predicted our fate to an unnervingly accurate degree.

And then the day came,

when the risk

to remain tight

in a bud

was more painful

than the risk

it took

to Blossom.

“

In other words, learning how to control shock with the body will help the mind recover from shock, and even further growth can be expected.

김지호

파쿠르 제너레이션즈 코리아 대표

Jiho Kim

President of Parkour Generations Korea

RELATED POSTS