A Basket of Summer Fruit

여름 과일이 담긴 광주리

02

Text by Guy Davenport 가이 다벤포트

Translation by Mimi Park 박상미

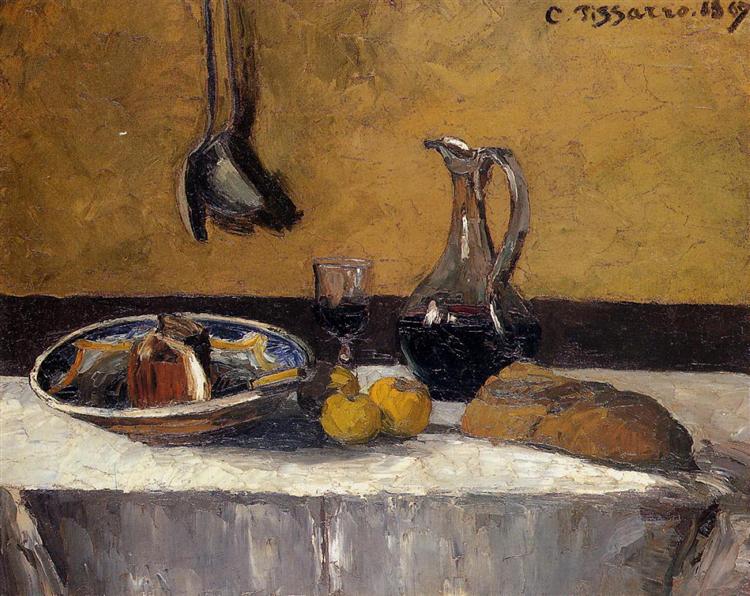

Still life is a minor art, and one with a residue of didacticism that will never bleach out; a homely art. From the artist's point of view, it has always served as a contemplative form useful for working out ideas, color schemes, opinions. It has the same relation to larger, more ambitious paintings as the sonnet to the long poem. Petrarch, Wyatt, Shakespeare, Milton, Donne, Hopkins-the sonnet is their study book and their confessional, their meditative form. It is easy to see that still life has been a kind of recreation, a jeu d' esprit, for painters. Manet painting a bunch of asparagus is a man on holiday, like Rossini and Mozart having fun writing comic songs, or Picasso doodling on a tablecloth.

We must not, however, imagine that still life is inconsequential or trivial. Composers work out ideas in string quartets-Beethoven's and Bartok's experimental forms for discovering what can be done with harmonies and tempi-that have become masterpieces. There are artists like Chardin and Braque for whom still life was their major form of expression, as there are poets who have excelled only in the sonnet and the short lyric.

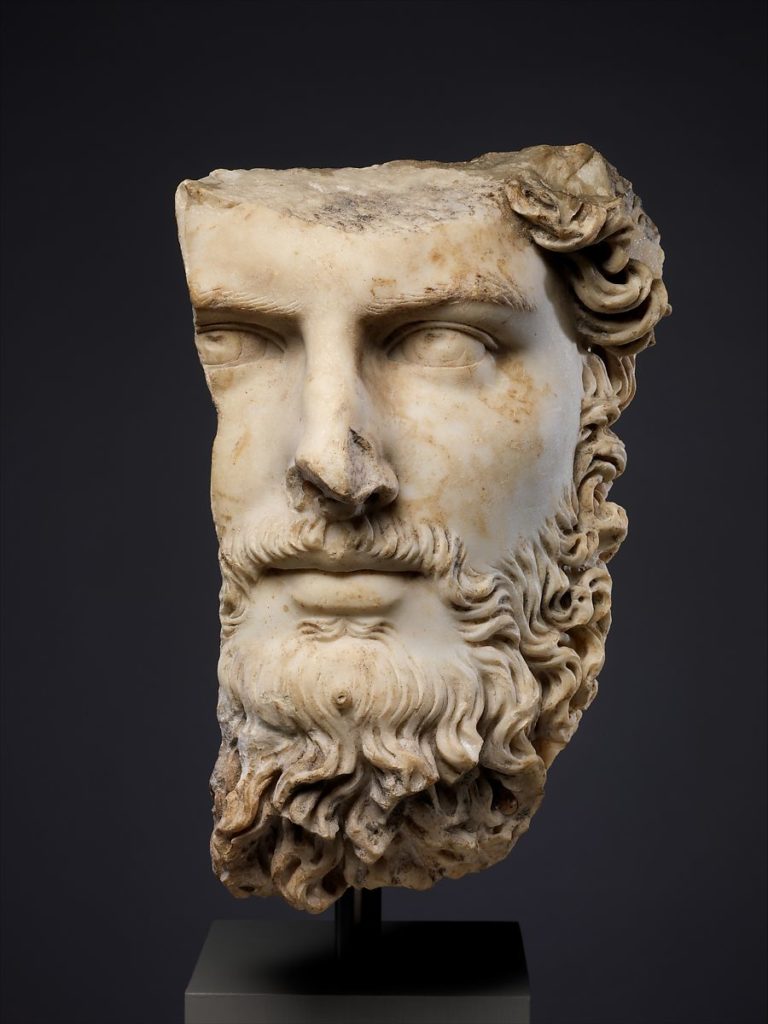

That the kinship of still life with still life down through history is greater than that of landscape with landscape, or portrait with portrait, lies at the center of its mystery. A Roman landscape in mosaic on the wall of a villa, with its archaic placement of trees and figures, its total lack of perspective, is a vision radically different from a medieval landscape with its toy charm and fidgety business (the woodcutter paying no attention to David carrying off Goliath's head; a fisherman in his boat in the river equally indifferent), or a Poussin, or a description by Proust of the meadows around Balbec. But a Roman mosaic of a basket of apples and pears, as in the Vatican's tessellated floor, is wonderfully like baskets of apples and pears of all ages. There is the same nakedness of presentation, the same mute hope of and confidence in the clarity of the subject, a tacitness so deep that we may never get to the bottom of it.

Reiteration is a privilege of still life denied many other modes. Turner's landscapes and interiors begin and end with Turner, not because genius does not repeat but because Turner's time, its spirit and perspectives in history, cannot repeat itself. Turner's wave of time was strong, percussive, and grand, but it was short. Still life belongs in the slow sinews of a great swell that began with the cultivation of wheat and the fermentation of wine, bread and wine being two of its permanent images. It is an art that is symbiotic with civilization. We must suppose that man in his most primitive state ate like a beast, selfishly and when he could.

Claude Levi-Strauss in his tetralogy Les Mythologies argues that in preparing food for communal consumption, by cooking, by symbolic understanding of the ritualness of eating, and by the evolution of table manners, we crossed over from the wild to the tame, from nature to culture. Certainly the placing of food on an altar to do honor to a god, which is one of the instigations of all still life, is an obvious passage from savagery to civilization, which the Bible locates at the beginning of time already differentiated into the hunter's and the farmer's sacrifice.

In Christ's ministry the table figures as a versatile symbol throughout the Gospels, from the wedding feast of the first miracle to the Last Supper, the bread and wine of which became fixed in European still life, along with other Christian symbols, such as the apple and the pear, which would not go away in the most gaudy Dutch still lifes, or in cubist still lifes, where, on the contrary, they asserted themselves with new vigor.

"Still life" first comes into English in Dryden and Graham's translation (1695) of Dufresnoys's De Arte Graphica, or The Art of Painting: "His peculiar happiness is expressing all sorts of Animals, Fruit, Flowers and the Still-Life." By 1701 the meaning seems to have narrowed in English to mean trompe l'oeil, and in 1762 we find Horace Walpole looking down his nose and writing, "He painted still-life, oranges and lemons, plate, damask curtains, cloths of gold, and that medley of familiar objects that strike the ignorant vulgar," from which we gather that the knowing had become bored with the Dutch pronkstillleven. In the third century B.C., by the way, there is a mime of Herondas in which he satirizes pretentious women for admiring the lifelikeness of paintings without understanding a great deal of what they were about:

That naked boy there, look, I could pinch him

And leave a welt. His warm flesh is so bright

that it shimmers like sunlight on water.

And his silver fire tongs; wouldn't Myllos

send his eyes out in stalks i.n wonderment,

or Lamprion's son Pataikiskos try

to steal them! For they are indeed that real!

The ox, the herd, and the girl who's with them

the hook-nosed man with his hair sticking up,'

they are as real as in everyday life.

If I weren't a lady, I might scream

at the sight of that convincing big ox

watching us out of the side of his big eye.

Here is a sixth-century B.C Greek table, described in an elegy by Xenophanes of Colophon:

The floor is clean, and all our hands, and the cups.

A slave puts garlands of flowers on our heads

another passes around myrrh in a flat dish, for perfume.

The mixing bowl and a jar of wine as sweet as honey

and smelling of flowers sits in our midst.

The room is scented with frankincense, and the springwater

for the wine is cold, fresh and pure.

Loaves of bread seem golden, and there is honey and cheese.

There is a bouquet of flowers on the altar in the center.

Xenophanes goes on to say that the meal begins with songs, prayers, and a libation. The prayer is that we might be just to all men. Conversation at a meal, he says, should be light and decent, with no long accounts of books you have read.

We have kept that sense of clean hands and tableware, we have kept the flowers in the middle of the table, and we have kept the sense of a meal as a social gathering with conversation. Still life has concomitantly guided the table as a civilizing occasion.

Greek poetry is rich in still lifes, as was their painting, as we know from the anecdote of the bird that tried to eat Apelles' cherries. Here is a poem to dedicate objects placed on an altar:

His green garden's twytined digging fork,

the curved sickle that pruned and weeded,

the comfortable old coat he wore in the rain,

and his raw oxhide waterproof boots,

the stick with which he set the cabbage sprouts

In long straight rows in rich black loam,

the hoe that chopped the runnels that kept

the garden green all the dry summer long,

for you, Gardener Priapos, the gardener Potamon,

whom you favored, places on your altar.

Another:

To Priapos, god of gardens and friend to travelers,

Damon the farmer laid on this altar,

with a prayer that his trees and body be hale

of limb for yet awhile, a pomegranate glossy bright,

a skipper of figs dried in the sun,

a cluster of grapes, half red, half green,

a mellow quince, a walnut splitting from its husk,

a cucumber wrapped in flowers and leaves,

and a jar of olives golden ripe.

정물화는 이급 예술이었고, 정물화에 남아있는 교훈적인 내용의 흔적은 결코 가시지 않을 것이다. 그러니까 그저 편안한 예술이다. 그런데 화가의 입장에서 정물화는 언제나 아이디어나 색채, 의견들을 실험해보는데 유용한, 사색하기 좋은 형태의 장르였다. 정물화와 더 크고 더 야망 있는 회화의 관계는 소네트와 긴 시와의 관계와 비슷했다. 페트라르크, 와이어트, 셰익스피어, 밀턴, 돈, 홉킨스- 이 모두에게 소넷은 그들의 연습장이었고 고백과 명상을 위한 형식이었다. 정물화는 화가들에게 있어 일종의 리크리에이션이고 기지에 찬 경구였다. 마네가 아스파라거스 한 뭉치를 그리는 것은 그가 휴가를 보내고 있다는 뜻이었다. 마치 로시니와 모차르트가 우스꽝스런 노래를 지으며 재미를 느끼거나 피카소가 탁자보 위에 낙서를 하는 것처럼.

그러나 우리는 정물화가 중요하지 않거나 사소하다고 생각하면 안된다. 작곡가들은 현악 4중주에서 그들의 아이디어를 실험했고 이들은 걸작이 되었다. 베토벤과 바르톡은 곡조와 박자가 어떻게 될 수 있는지 현악 4중주에서 이들을 실험했다. 샤르댕과 브라크에게 정물화는 그들의 주요 형식이었다. 소네트와 짧은 시들만 잘 쓰던 시인들이 있는 것처럼 말이다.

역사를 통해 한 정물화가 다른 정물화에 갖고 있는 일종의 혈연 관계는 다른 장르들, 즉 풍경화가 풍경화에 대한, 초상화가 초상화에 대한 그것보다 훨씬 두텁다. 이는 정물화가 지니는 본질적인 미스터리다. 로마의 빌라 벽에 장식된 모자이크 풍경화는, 그 나무와 인물의 어색한 배치나 원근법이 전혀 고려되지 않은 점이 중세의 풍경화와는 완전히 다른 모습을 보여준다. 매력적이고 어수선한 작은 인물들이 보이는 (다비드가 골리앗의 머리를 들고 있을 때 이에 아랑곳 않고 나무를 베고 있는 인물이나, 관심이 없기는 마찬가지인, 강에서 고기를 잡는 어부의 모습이나) 중세의 풍경화는 푸생의 풍경화나, 프루스트가 발벡* 근처 초원을 묘사한 것과는 매우 다르다. 그러나 사과와 배가 담긴 바구니가 있는 로마의 모자이크는, 바티칸의 모자이크 바닥에서 볼 수 있는 것처럼, 다른 시대의 사과와 배가 담긴 바구니와 그 모습이 놀라울 정도로 비슷하다. 그 표현 방식의 '벌거벗음'이나 소재의 명료한 표현에서 오는 조용한 희망과 자신감, 그 과묵함의 깊이는 아주 깊어서 우리가 헤아릴 수 없을 정도다.

*프루스트의 "잃어버린 시간을 찾아서"에 나오는 가상의 지명으로, 노르망디의 실제 바닷가 휴양지인 카부르Cabourg를 모델로 했다.

반복은 다른 장르에서는 불가능한, 정물화만의 특권이다. 터너의 풍경화와 실내화는 터너에서 시작하고 터너에서 끝나는데, 그가 천재라서 그런 것이 아니라 터너의 시간 자체가 갖는 성격과 역사적 맥락 때문에 반복이 불가능한 종류였기 때문이다. 터너가 가져온 파장은 매우 강하고 임팩트 있고 대단했지만, 그 길이가 짧았다. 정물화에 영원히 등장하는 소재 중 두 가지가 빵과 와인이라면, 정물화는 밀의 경작, 와인의 숙성과 함께 시작하는, 완만하게 부푸는 거대한 곡선의 일부이다. 이는 문명과 공생하는 예술이다. 가장 원시적인 상태에서 살았던 인간은 짐승처럼, 이기적으로 아무때나 음식을 먹었을 것이다.

클로드 레비-스트로스는 그의 신화학 4부작에서 음식을 다른 사람들과 나누어 먹기 위해 음식을 준비하는 과정에서, 그러니까 음식을 조리하고, 먹는다는 의식에 대한 상징적 의미를 이해하고, 식사 예절을 발전시키면서, 우리는 야생에서 문명으로, 자연에서 문화로 넘어오게 되었다고 주장한다. 물론 신에게 바치기 위해 제단에 음식을 올리는 행위- 모든 정물화의 근원 중 하나인-는 야만에서 문명으로 오는 분명한 과정이다. 이는 성경에서 태곳적부터 사냥꾼과 농부의 희생이 구분되어 밝혀진 지점이다.

복음서들을 통해 줄곧 나타나는 그리스도의 행적을 보면, 결혼식 연회의 첫번째 기적* 에서 마지막 만찬까지, 식탁은 다양한 상징과 함께 그 중요성을 드러낸다. 빵과 와인은, 사과와 배와 같은 다른 상징물들과 함께, 유럽 정물에 단골로 등장하는 소재가 되었다. 이들은 사라지지 않고, 최고로 호화로운 네덜란드 정물에서 큐비즘의 정물화까지 줄곧 등장하며, 그럴 때마다 오히려 새로운 활력으로 그 모습을 재주장했다.

*갈리리 가나에서 열린 결혼식에서 예수는 물을 와인으로 만든다.

영어 "Still life"는 뒤프레스노이의 <회화의 예술 De Arte Graphica, The Art of Painting>을 드라이덴과 그레이엄이 번역한 책(1695)에서,- "그는 별의별 동물들과 과일, 꽃과 정물을 표현할 때 유별나게 행복했다."-처음 등장했다. 1701년에는 그 의미가 트롱프레유에 국한되는 듯이 보였고, 1762년에 호레이스 월폴* 은 정물화를 업신여기며 이렇게 썼다. "그는 정물을 그렸다. 오렌지와 레몬, 접시, 다마스크직 커튼, 금박 장식의 천, 그 일상적인 물건들의 조합은 무식하고 천박하게 느껴진다." 이를 통해 우리는 당시 지식인들이 네덜란드의 프롱크스틸레벤에 질려가고 있었음을 알 수 있다. 기원전 3세기에는 그런데, 헤론다스*는 마임에서 한 여자가 어떤 그림을 보고, 그 진정한 의미는 이해하지 못하고 실제와 닮게 그렸다고 아는 척하며 찬사를 보내는 것을 보고 풍자했다.

*호레이스 월폴 Horace Walpole(1717-1797)

영국의 미술사가, 교양인, 정치가, 작가

*헤론다스Herodas (?-?)

기원전 3세기 경 그리스의 시인이자 시극 작가. 헤로다스로도 불린다. 미미얌보이 또는 마임이라 불린, 당시 유행하던 이 시극은, 평민의 언어를 사용한 일상생활 속의 주제를 해학적이고 때로 노골적으로 표현했다.

저기 저 벌거벗은 소년을 봐, 꼬집을 수 있을 것 같아

그러면 살이 부풀어 오를 거야. 따뜻한 살결이 눈부셔서

물에 비친 햇살처럼 빛나고 있네

그리고 그의 은 부젓가락: 밀로스가 저걸 보면

놀라서 눈이 튀어나오지 않을까?

아니면, 람프리온의 아들 파타키스코스가

훔치려들지도 몰라. 그 정도로 진짜 같아!

황소, 양떼, 거기 있던 작은 소녀,

머리가 뻣뻣하게 선 매부리코 남자,

다들 모두 진짜 같아.

내가 숙녀가 아니었다면, 우리를 그 큰 눈으로 째려보는,

그 진짜 같은 커다란 황소를 보고 비명을 질렀을 거야

기원전 6세기엔, 콜로폰의 크세노파네스*의 애가에 그리스 식탁이 등장한다.

바닥은 깨끗하다. 그리고 우리의 손도, 그리고 컵도.

종 한명이 우리 머리에 화관을 씌우고,

다른 하나는 납작한 접시 위에 몰약을 돌린다, 향기를 위해서.

음식을 섞는 그릇과 꿀처럼 달콤한 와인이 담긴 단지

그리고 꽃 향기가 우리 가운데 머문다.

방은 유향 내음으로 그득하고, 그리고 와인을 위한

샘물은 차고 신선하고 순수하다.

황금색 빵 덩이와, 꿀과 치즈도 있다.

탁자 가운데 제단에는 꽃 한 다발이 놓여있다.

*크세노파네스 Xenophanes(BC 570 - BC 480)

BC 565년경 출생한 그리스 철학자이며 시인이다. 소아시아의 콜로폰 사람으로, 어려서 고향을 떠나 100세가 되도록 그리스 각지를 유랑하였다. 그리스인들의 믿음과 의인적인 신관에 비판을 가하였다. 그는 '하나로 하여 일체가 되는 것' 을 신이라고 보는 범신론의 입장을 취하였다.

크세노파네스는 이에 더하여 식사는 노래와 기도와 헌주로 시작한다고 말한다. 모든 이에게 공평해야 한다는 기도를 하고, 식사 중 대화는 가볍고 점잖게, 자기가 읽은 책에 대해 길게 말하지 않는 것이 좋다고 했다. 우리는 식사 전에 손과 식기를 깨끗하게 하고, 식탁 중앙에는 꽃 장식을 놓고, 식사가 대화를 수반하는 사교가 될 수 있다는 생각들을 유지해온 것이다. 정물화는 그에 수반해서 식탁을 문명의 표상으로 이끌어왔다.

그리스의 시에는 그들의 그림에서와 마찬가지로 정물이 풍부하게 등장한다. 아펠레스의 체리를 먹으려던 새의 일화에서 알 수 있다. 여기 제단 위에 놓인 정물들을 기리는 시가 있다.

그의 푸른 정원에 있는 목마른 흙을 파는 쇠스랑,

가지를 치고 잡초를 베는 구부러진 낫,

그가 비옷으로 입던, 낡고 편안한 외투,

그리고 그의 소가죽 방수 부츠,

그가 검고 비옥한 땅 위 길고 곧게 줄줄이

양배추 싹을 놓을 때 쓰던 막대기,

건조한 여름 내내 정원을 푸르게 해주던

도랑을 파던 호미,

정원사 프리아포스*, 당신을 위해,

당신이 좋아하던 정원사 포타몬이

이들을 당신의 제단에 바칩니다.

*프리아포스 Priapus

야채 정원의 신이고, 양봉과 양떼, 포도밭의 보호 신이기도 하다.

하나 더 있다.

정원의 신 그리고 여행자들의 친구, 프리아포스에게,

농부 다몬이 이 제단에 바칩니다.

그의 나무들과 신체가 건강하기 바라는 기도와 함께,

밝게 반짝이는 자몽 한 개,

볕에 말린 무화과 한 바구니,

반쯤은 붉고 반쯤은 푸른, 포도 한 송이,

그윽한 향의 모과, 껍데기가 벌어진 호두 한 알,

꽃과 잎에 싸인 오이 하나,

금빛으로 익은 올리브가 담긴 단지 하나.

RELATED POSTS