Korean Aesthetics and the Identity of Mahk

한국의 미학과 막의 정체성

02

Text by Byoungsoo Cho 조병수

Translation by Mimi Park 박상미

Across all arts, traditionally, Korea holds little regard for straightforward perfection. If we study the docility of the Zen gardens at the Ryōan-ji temple or the muted refinement of Chashitsu (tea houses) in Japan, we encounter environments who hold unassuming simplicity in appearance only. Their humble demeanors are in truth the product of considerable planning beforehand. Korean arts, on the other hand, willingly give up refinement for the sake of true improvisation on every level.

This coarse spontaneity has become less outwardly apparent in Korea since the end of the Josun dynasty in the first decade of the 20th century. In the 1930s and 1940s, under Japanese settler colonization, even the Korean language itself was banned from school and public life. In the decades that followed, Westernization and Christianity swept the nation, and many traditional Korean practices were shunned in favor of modernization. Thus much of the true spirit of Korean creativity has for some time been on decline-forgotten and covered up, often unknowingly. For example, many restorations of ancient Korean buildings, in the first half of the last century, were done in the style of Japanese buildings of similar time periods (Kwon). Slowly artisans and creators of all kinds are lifting the layers that disguised true Korean artistic tradition.

Renewed interest in original Korean values and aesthetics, as well as the realization that perhaps our traditions are not inferior to Western, Japanese, Chinese, or any others, have spurred a new rise of modern Koreans who are well versed in foreign as well as native considerations in art and design. Contemporary Korean art can be seen in lineage with these traditional ideas. Artists such as Park Seobo and Ufan Lee paint with an attention to the informality between fabrication and emotion that relentlessly harbors this rawness.

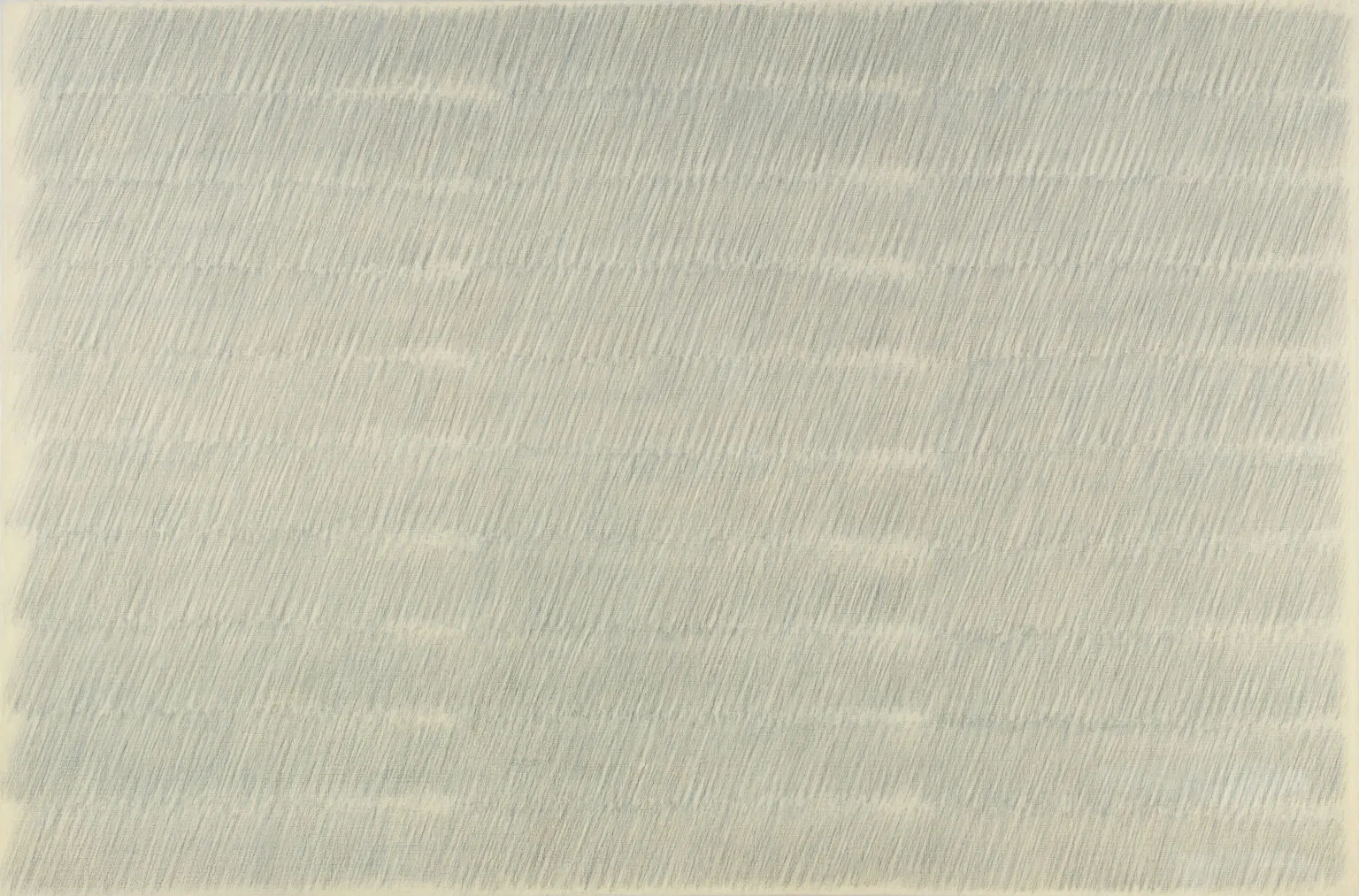

In a piece by Seo-Bo Park, repetitive streaks of pencil scrape across a canvas, excavating a thick layer of oil paint as they proceed up and down, back and forth, not unlike the works of Cy Twombly in the late 1960s. Nevertheless, something emanates from the piece that is encountered nowhere else. Where Twombly's marks are sharp, like many of his American contemporaries, Seo- Bo's fade through the viscosity of their heaping paint. The work is as much about a pencil's encounter with thick pigment as it is about the sequential maneuvering of the artist's hand across the canvas. Contemplative yet materially consequential, the work engages a marked balance between artistry and meditation, as if to absolve through silent repetition the meaningfulness of anything beyond the immediacy of a creative act. That the painting speaks to such extents about its own making should be of little revelation when considering its own title, 'Ecriture', signifies the action of writing (p.230-231). Beyond mere conveyance of words, Park considers the tactile implication of a hand's interaction with a canvas without the overbearing teleology of meaning.

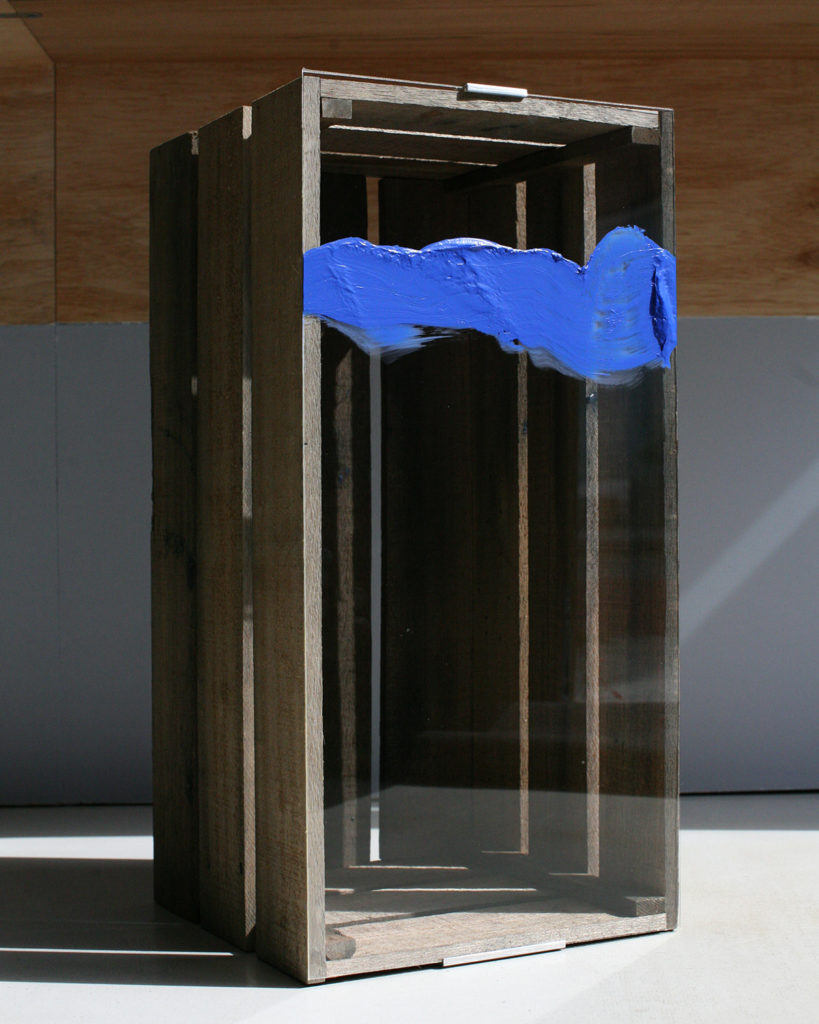

Another work expounds this examination of process to an even further degree. In this case, Chong-Hyun Ha's 'Conjunction', coerces form from the seepage of paint between cracks of paper (p.232-233). To examine its making is to understand the delicate boundaries between which mahk frolics. That is to say, this intuitive attitude towards making equitizes the components which constitute an artwork while levying a particular space of uncontrollability in the spontaneity of materials. It is a reconciliation with the elemental messiness of that which surrounds us. Thus, of important note is that Chong-Hyun does not himself sculpt the painted forms which so immensely define the essence of his work. Rather, he entices their emergence through the process of making.

Even throughout modernist architecture in Korea, we witness "Korean identity in spaces focusing on qualities of emptiness, non-existence and [bium]", notes Hyungmin Pai, co-curator of the award-winning Korean pavilion at the 2014 Venice Biennale. As a new generation has taken the reigns of architecture in Korea, many, myself included, have considered anew what it means to design from this standpoint. In my own work, it is with a deliberate vocabulary of rough materials and a process focused on the intimate spontaneity and honest beauty for which mahk and bium allow.

*

Works Cited

A. B. Cook (1914), Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, Vol. I, p. 104, Cambridge University Press.

Cartwright, Mark. "Korean Pottery." Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 25 Oct 2016. Web. 16 Jan 2020.

Choi, Wan Gee (2006). The Traditional Education of Korea. Ewha Womans University Press. pp. 29-30. ISBN 9788973006755. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

"Chosŏn dynasty: Korean history". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

Kwon, Heonik "Healing the Wounds of War: New Ancestral Shrines in Korea," The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 24-4-09, June 15, 2009.

Leaman, Oliver (Oct 19, 2006). Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy. Routledge. p. 143. ISBN 9781134691142. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

Szczepanski, Kallie. "The Ceramic Wars: Hideyoshi's Japan Kidnaps Korean Artisans." ThoughtCo, Jul. 3, 2019, thoughtco.com/ceramic-wars-hideyoshis-japan-kidnaps-koreans-195725.

"막"은 미적 통일성이 아닌 각각의 불완전함을 받아드릴 때 비로소 완성된다. 일본의 '와비사비'정신은 완전한 형태를 만든 후 약간 비틀어 놓음으로써 만들어지는 자연스러움으로 정의되는 반면, "막"은 솔직담백하게 만들어가며 빚어진 여유의 자연스러움이라 하겠다. "막"의 작품들은 얼핏 보았을 때는 인상적이지 않을 수 있으나, 그들의 목적은 이를 지켜보는 관객을 감동시키는 것이 아닌 창작의 작업 안에 있는 예술가와 장인의 창조적 행위이므로 일단 완성이 되면 그것으로 가장 훌륭한 쓰임이 되는 것이다. 한국의 "막", "비움" 과는 대조되는 일본의 미니멀리즘의 차이점을 극명하게 보여주는 한 예로 일본의 현대건축에서 흔히 찾아볼 수 있는 정제되고 정교한 건물들과 달리 거친 콘크리트 외관을 지닌 서울의 모습을 말할 수 있겠다. 보여지는 모습에 개의치 않는 "막" 의 아름다움은 스스로 확신에 차 있으며, 계획되지 않은, 자유로운 방식 속에서 물리적 아름다움의 빛을 발한다.

영향력 있는 한국 화가이자 사상가인 '이우환'은 조선 도예의 '달 항아리'를 아무런 저의없이 정직성을 표현하는 것이라 말한다. 또 이는 만드는 이의 기술이 충분히 높은 경지에 다다랐을 때 이렇게 자연스럽게 나타날 수 있는 것이라 덧붙였다. 두 개의 그릇을 결합하여 만들어진 '달 항아리'의 미묘하게 기울어진 윤곽은 그 자체로서 하나의 추상예술에 가깝다.

이렇게 만드는 과정과 재료가 그대로 드러나는 날 것에 가까운 '달 항아리'는 "예술작품으로서의 완벽과 현실성의 결여"로부터 "주위환경과 완벽히 동화됨"을 보여준다.

또 하나의 좋은 '막'의 예는 한국의 승무이다.

무용수들이 짜여진 안무가 아닌 공연의 리듬 속에서 순간순간 즉흥적인 변화를 만들어가며 춤추는 모습을 볼 수 있다. 이렇듯 전통적인 한국의 모든 예술은 전반적으로 직설적인 완벽함을 추구하지 않는다. 일본의 료안지 정원이나 일본의 정제된 전통 다실에서 발견되는 '정제된 자연스러움'은 작업의 처음부터 계획된 산물인 반면 한국의 예술은 '덜 다듬어진 채로 남겨진 자연스러움'을 추구하는 것이며 이를 "막"이라 말할 수 있겠다.

이 거친 즉흥성은 20세기 초 조선의 멸망과 함께 현대화의 과정을 거치며 한국의 예술 속에서 점점 찾아보기 힘들게 되었다.

1930-40년대에는 일본의 식민지 지배하에 학교를 비롯한 모든 공식 석상에서 한국어조차도 일절 사용하지 못하게 되었고 그 이후에도 급격한 서구화와 기독교의 유입으로 인해 한국의 많은 전통들이 현대화라는 그림자에 가려져 한국의 창작 혼은 쇠락의 시기를 맞았고 이 때부터 점차 잊혀져 어둠 속에 묻혀지게 되었다.

그러나 최근 30-40년간, 한국의 예술가들과 창작자들은 한국의 예술적 전통을 가리고 있던 장막을 서서히 걷어 올렸다.

그리고 한국의 정치·경제적 발전과 더불어 한글 등을 통한 영향으로 한국의 전통적 가치와 미에 대한 관심이 다시 생겨나게 되면서 외국 뿐만 아니라 우리 고유의 예술과 디자인에 정통한 현대인들 사이에서 우리의 전통이 서양, 일본, 중국 등에 비해 열등하지 않다는 깨달음을 갖게 되었다.

현대 한국 예술을 들여다보면 위에 기술한 것과 같은 "막"의 한국 전통에 깊게 뿌리 내리고 있음을 발견한다. 박서보, 이우환 화백과 같은 예술가들은 감정과 물리적 조작 사이의 관계에 주목하여 막의 미학을 발견해낸다. 2014년 베니스 비엔날레에서 열린 한국관 공동 큐레이터 배형민 교수는 "한국의 현대 건축가들 사이에서도 공허 혹은 비움에 중점을 둔 공간에서 한국의 정체성을 찾는다"고 언급했다. 새로운 세대의 건축가들이 한국건축을 이끌어가는 이 시점에, 나 자신을 포함한 다수가 이러한 맥락 속에서 디자인이란 무엇을 의미하는가에 대해 다시금 새롭게 생각하고 있다. 나에게 있어서는, 거친 소재의 사용 그리고 즉흥성과 정직한 아름다움에 집중할 때 만들어지는 작업과정이 만들어내는 순수한 아름다움인 "막"과"비움"이다.

RELATED POSTS