What is Berry Schwabsky Reading Now?

배리 슈왑스키는 무슨 책을 읽고 있나?

01

Text by Barry Schwabsky 베리 슈왑스키

Translation by Mimi Park 박상미

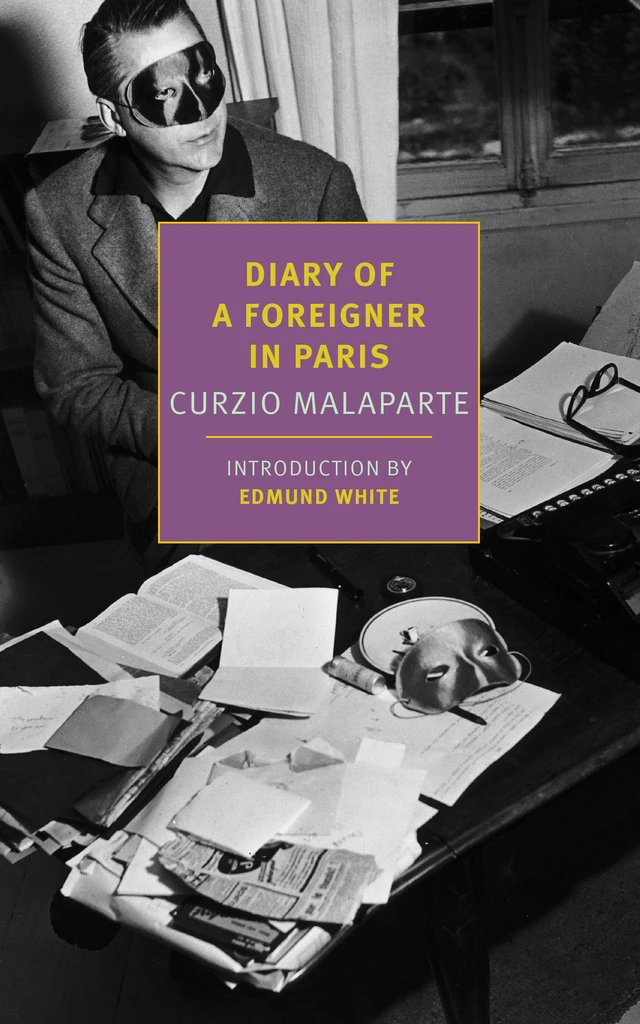

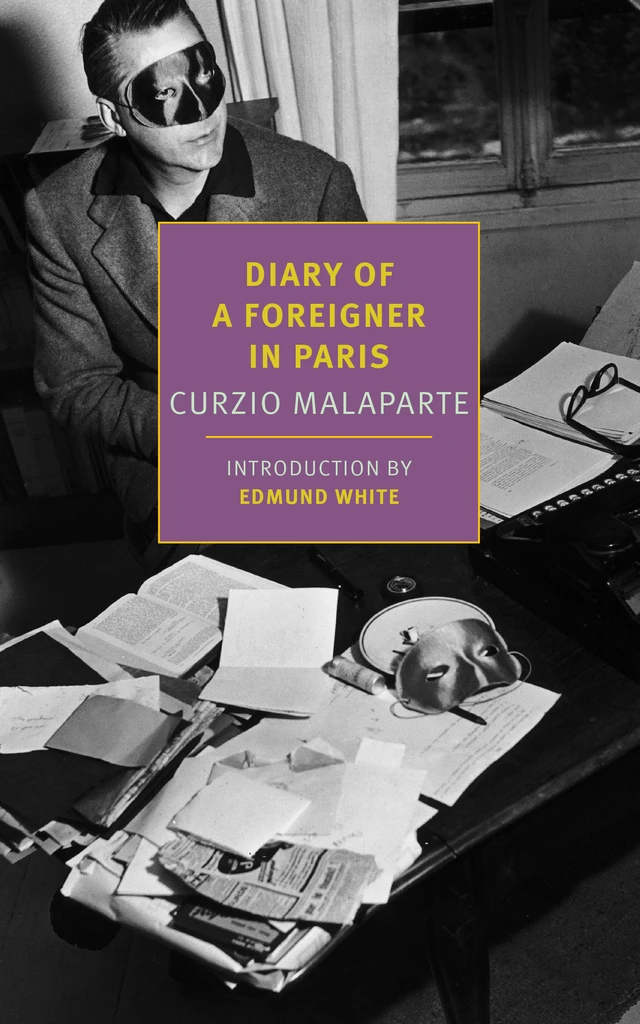

Diary of a Foreigner in Paris

Curzio Malaparte

Translated by Steven Twilley

Introduction by Edmund White

(2020)

파리의 이방인 : 일기

쿠르지오 말라파르트 저

번역 스티븐 트윌리

서문 에드문드 화이트

(2020)

내가 쿠르지오 말라파르트에 관심을 갖게 된 이유는 무엇보다 작가가 지은 자신의 이름, 나쁜 쪽을 택한다는 선언과도 같은 그의 이름 때문이다. 하지만 그의 책 <파리의 이방인: 일기>의 경우, 이 책에 끌린 이유는 이방인들의 도시였던 20세기 파리가 주는 유혹 때문이었다. 1947-48년 일부는 프랑스어로 일부는 이탈리아어로 쓰인 이 일기는 출판을 염두에 두고 쓰인 것으로 보인다. 또는 말라파르트의 자전적 소설의 재료로 쓰였을지도 모른다. 그가 자전적 소설을 썼다면 전후 파리의 유명한 인사들(카뮈, 콕토, 사르트르가 총 출연했을 것이다)과 지금은 잊혀진 배우들, 그리고 독자들을 이방인으로, 동시에 인사이더로 느껴지게 하는, 뒷얘기를 일삼는 사교계 인사들로 북적였을 것이다.

그런데 왜 이 프로젝트가 이루어지지 않았을까? (이 일기는 말라파르트 사후 이탈리아어로 1966년 처음 출간되었다.) 내 생각으로는 종종 "인종"으로 개념화되는 국가의 인물들에 대한 일관적이지 못한 생각들이 정리하기가 힘들었기 때문이 아닐까 한다. 데카르트는 그의 국가주의적인 철학이 프랑스인들의 사고와 실패의 원인의 핵심을 담아냈다고 생각했을까? 말라파르트의 책에서 인상적인 것은 깔끔한 스토리텔링과 잔인함의 모드이다. 어디서 들은 말인지 직접 본 건지 알 수 없지만, 그의 일화들은 종종 펀치라인을 담은 코믹한 이야기들 같은데, 종종 펀치라인들은 웃기기보단 서늘한 것이다. 한 예로, 1870년 파리 포위전 때 모든 사람이 굶주릴 때 이야기다. 한 남자가 먹을 것이 없어지자 집에서 키우던 개를 고려해야 하는 상황이 되었다. "식사 도중 불쌍하게 죽은 개의 뼈가 접시에 쌓여가는 걸 보며 그의 주인이 눈물을 흘리며 이렇게 말했다. '아, 이 뼈다귀들…..우리 불쌍한 파이도가 있었다면, 얼마나 좋아했을까!" 또는 스페인 내전 때, 한 포로가 처형장으로 걸어가는 일화로 이런 얘기도 있다. "겨울이었고, 시에라 산맥에서 오는 차가운 북풍이 불고 있었다." 처형수들도 찬 바람에 불평하는 포로들보다 옷을 따뜻하게 입지는 않았다. "간수 중 한 사람이 이렇게 말했다. '불평을 해? 우리를 생각해봐. 여기까지 왔는데 또 다시 돌아가야 하잖아!'" 말라파르트 역시 생존자의 자기 연민에 대해 좀 아는 사람이었다.

RELATED POSTS