The Importance of Philip Guston

필립 거스통의 중요성

Text and translation by 박상미 Mimi Park

“어떤 기운이 작용하고 있어. 모든 게 예측불허라고.”

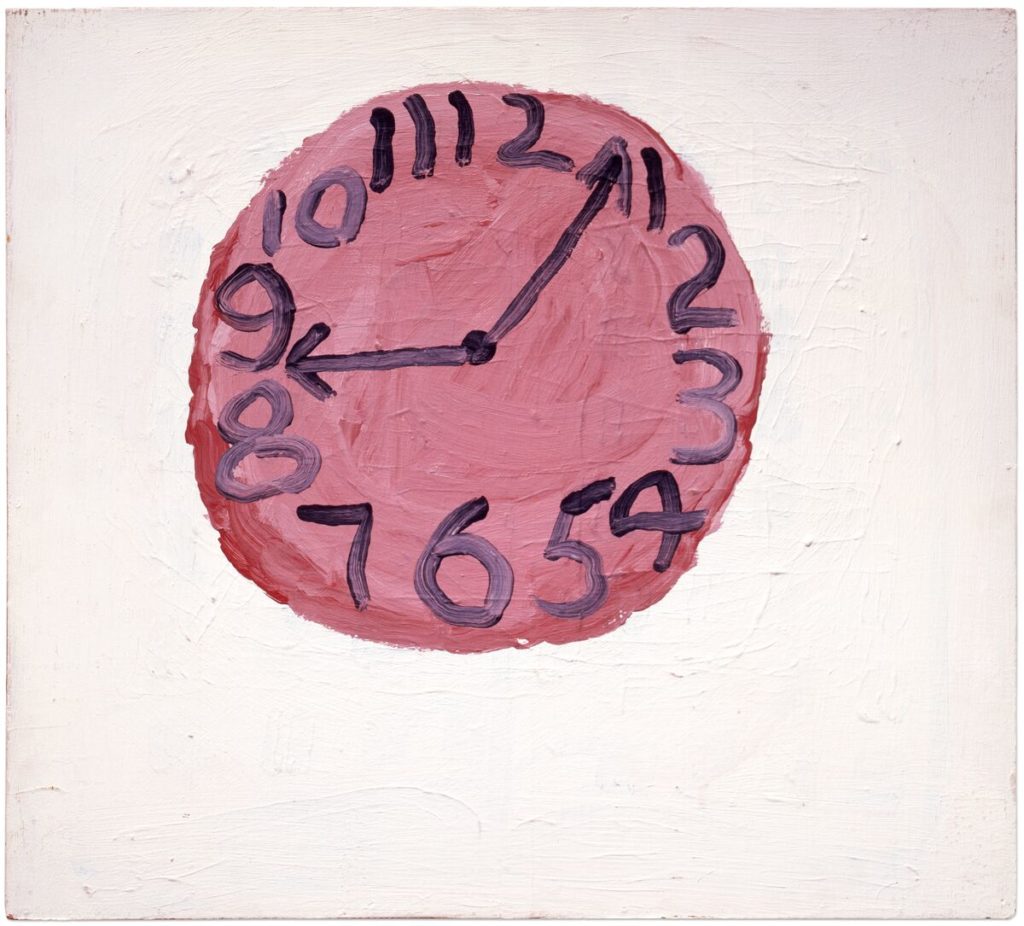

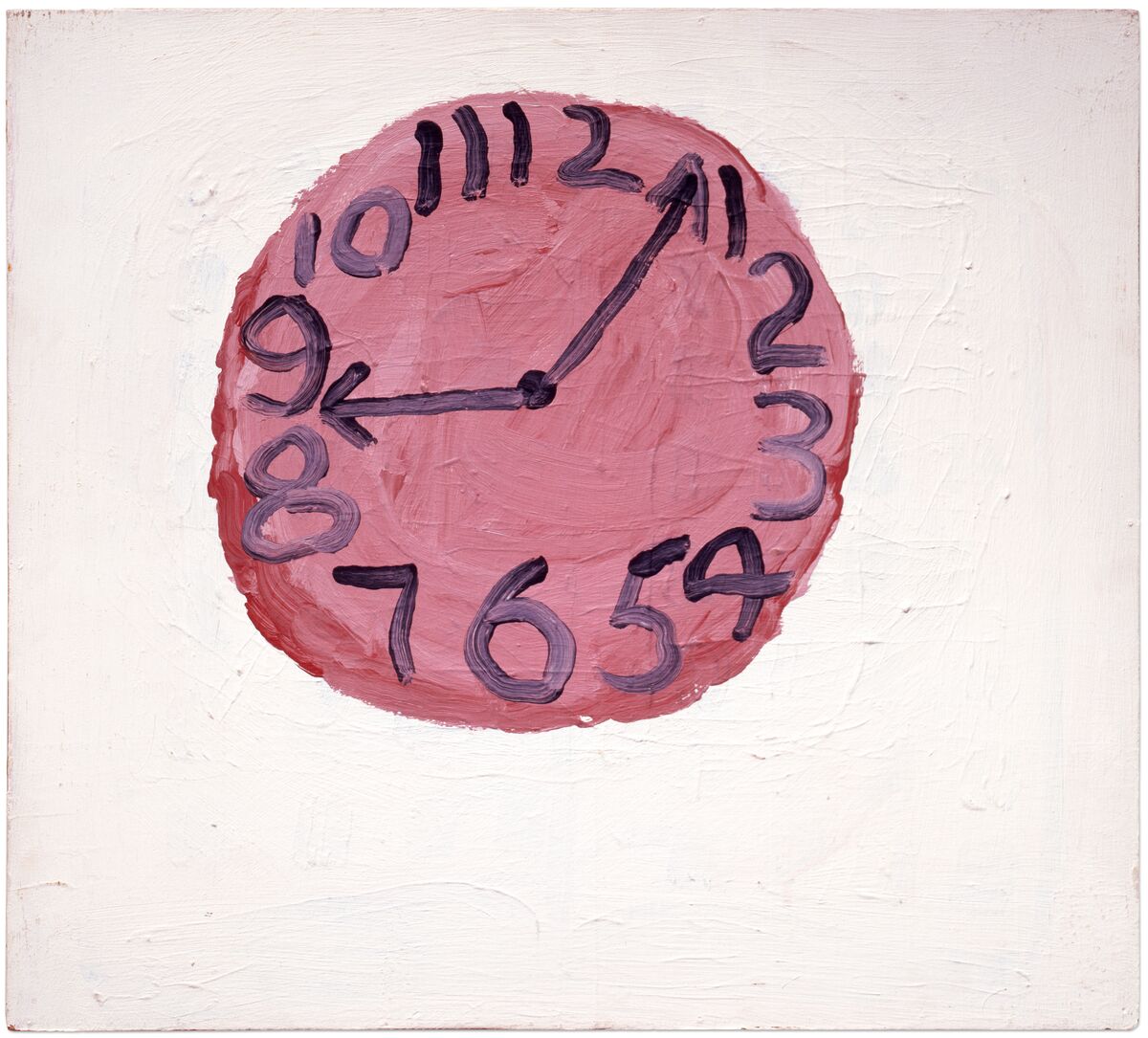

내가 “working around the clock(밤낮없이 일하다)”이라는 영어 표현을 배운 건 “밤의 작업실: 필립 거스통의 전기Night Studio: A Memoir of Philip Guston”을 읽을 때였다. 이 책은 필립 거스통의 딸인 뮤자 메이어Musa Mayer가 아버지를 가까이서 보고 겪으며, 그의 작품 세계는 물론, 가족 관계를 포함한 그의 삶을 전체적으로 그린 책이다. 아름다운 추상 회화를 그리던, 성공적으로 커리어를 이끌어가던 거스통이 갑자기 1967년부터 변화를 겪을 때, 미친 사람처럼 밤낮을 가리지 않고 작업에 몰두했다고 한다. 쉬지 않고 드로잉을 했고, 주변의 사물들을 하나하나 그리기 시작했다. 마치 새로 말을 배우는 아이 같이, 그가 발견한 새로운 언어로 사물들을 그려나갔다. 그가 그리던 사물들 중에는 시계가 있었고, 전등이 있었다. 책의 제목도 “밤의 작업실”이었다. “Working around the clock”이라는 말이 그대로 와닿았다.

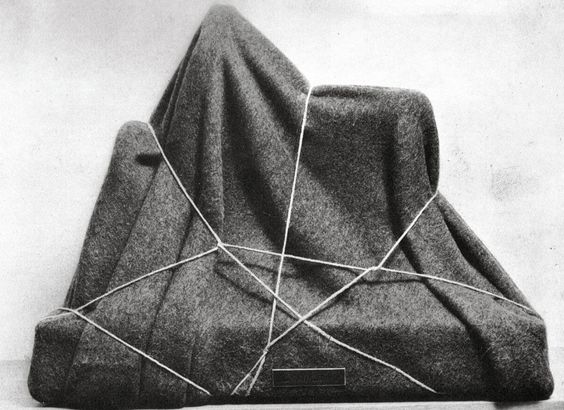

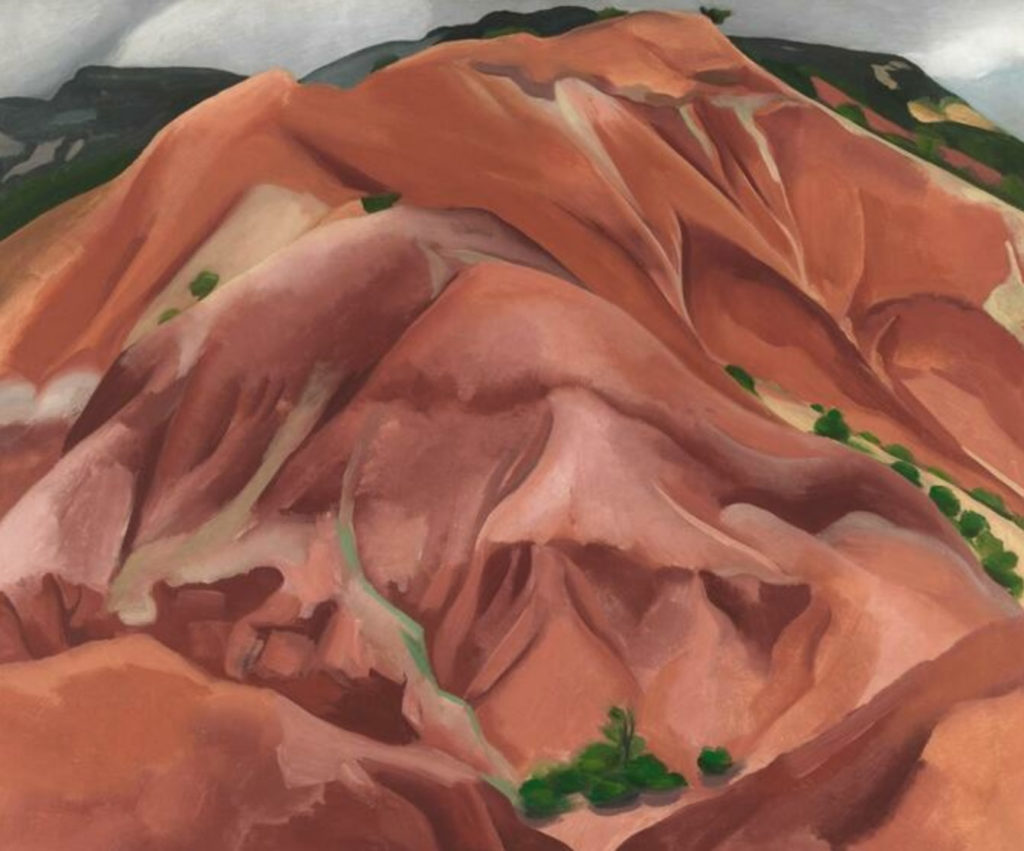

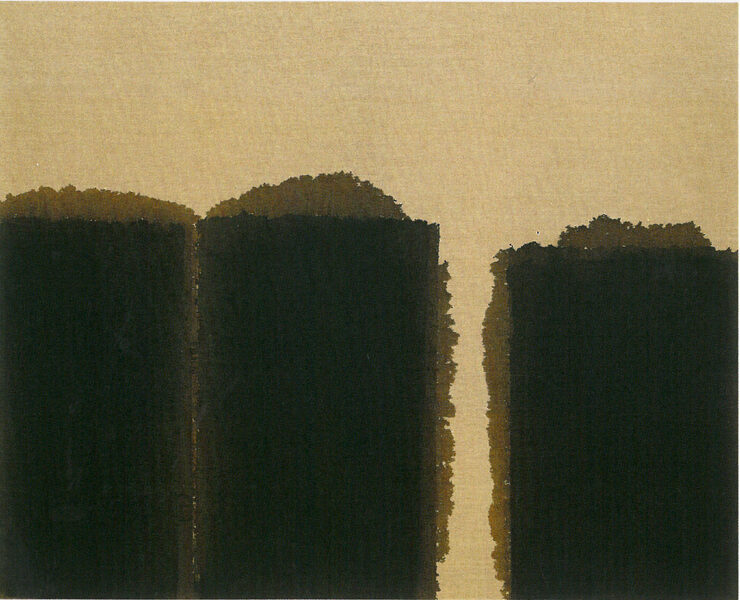

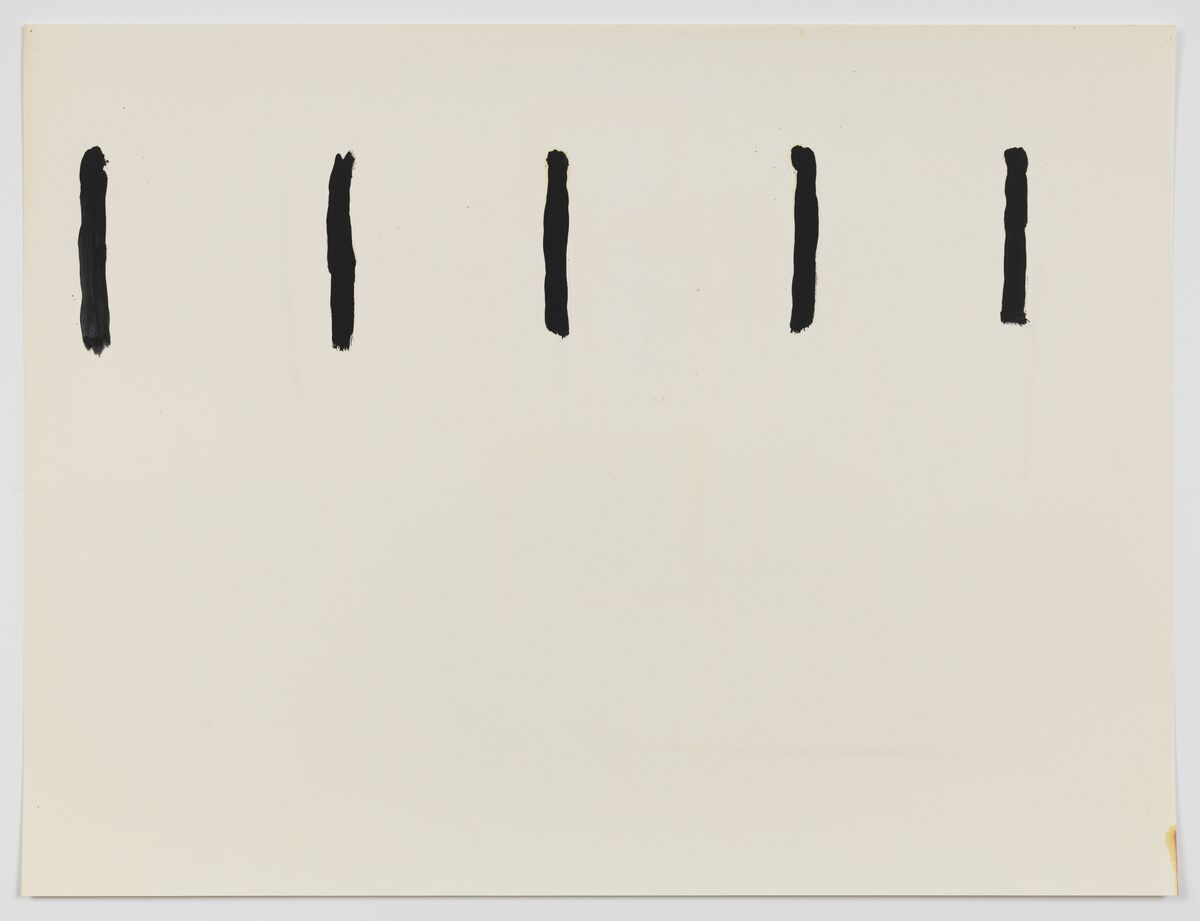

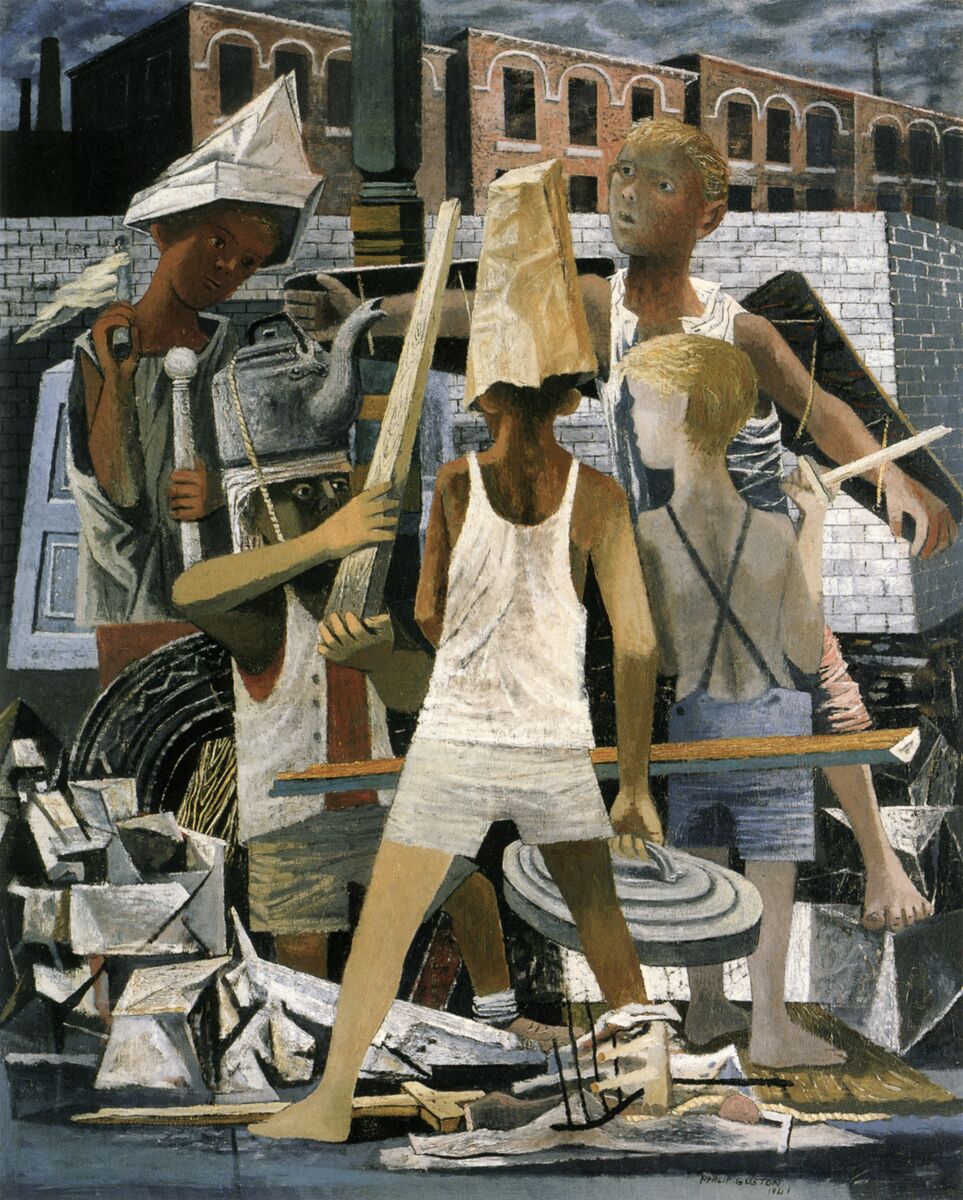

이 책을 읽은 후 거스통은 나에게 중요한 작가가 되었다. 그 이유는 여러가지가 있다. 그의 초기 구상 작업이 나에게 역시 중요한 작가들인 조르지오 디 키리코와 피에로 델라 프란체스카의 영향을 보인 것, 몬드리안의 수직, 수평선을 연상시키며 금방 난 상처처럼 붉은 색으로 흔들리는 그의 초기 추상 작품들, 그리고 폭력적이고 파워풀한 시정을 담은 그의 구상 작품들까지 내 머릿속에 크게 각인되었다. 하지만 무엇보다 가장 큰 이유는 그의 ‘탈바꿈’의 과정 그 자체, 그리고 그 과정에서 나온 작품들이다. 그때 그가 그린 하나 또는 두 개의 선, 꺾어진 선, 둥글린 선, 짧게 자른 선, 또 주저하며 그린 듯한 원. 그 비어있음이, 동시에 꽉 차있음이 충격적이었다. 그 다음에 드러나는 사물의 형태, 책, 시계, 구두, 도시 등은 뭔가 원시적이면서도 단단했다. 날 것이며 서투르면서도, 의미가 실려있는 하나의 단어처럼, 어떤 결정체 같았다. 어리석어 보이면서도 현명하고, 아주 오래된 것 같으면서도 생전 처음 보는 형태들이었다.

거스통의 경력에서 있어 크게 두 번의 작업세계의 전환이 있었는데, 한 번은 구상에서 추상(1947년 경), 두번 째는 추상에서 다시 구상으로 가는 전환(1967년 경)이었다. 마르셀 뒤샹이 작품 활동을 접고 체스 플레이어가 된 것이 뒤샹을 이해하는 주요 요소가 되듯, 거스통에게는 그의 이러한 전환 자체가, 그 과정 자체가 그의 작업 세계의 일부라고 할 수 있다.

“내가 거의 처음부터 다시 그림을 그린다면 무슨 일이 일어나는지 보고 싶었어요.”

거스통의 첫번째 작업 세계의 전환은 그의 동료들이 모두 추상표현주의로 중요한 변화를 겪을 무렵이었다. 그는 르네상스 화가들처럼 철저한 밑그림과 계획을 바탕으로 그림을 그리던 작가였는데, 모든 걸 처음부터 새로 시작하고픈 추동을 느꼈다. 그림을 그리는 주된 방법론이 변해야 했다. 그는 “뒤로 물러서서 보지 않은 채로 그림을 완성하는” 룰을 세웠다. 뒤로 물러서서 그림을 보지 않는다는 얘기는 자신의 그림을 안보고 그리겠다는, 시각적 판단을 포기한다는, 뭔가 내려놓겠다는 얘기다. 이제까지 배우고 닦아온, 현실을 묘사하는 능력도 버리고, 그림을 구성하는 지식과 관련된 통제력도 버리고, 자신의 그림을 판단하는 자아도 버리겠다는 얘기다. 그는 모든 걸 버리고 그림 안에 있었고, 그림에 더 “개입involved” 한 것이다. (그는 언젠가 인터뷰에서 happy라는 말을 “involved”라고 번복한 적이 있었다. 그에게 행복이란 involve하는 것이었다.)

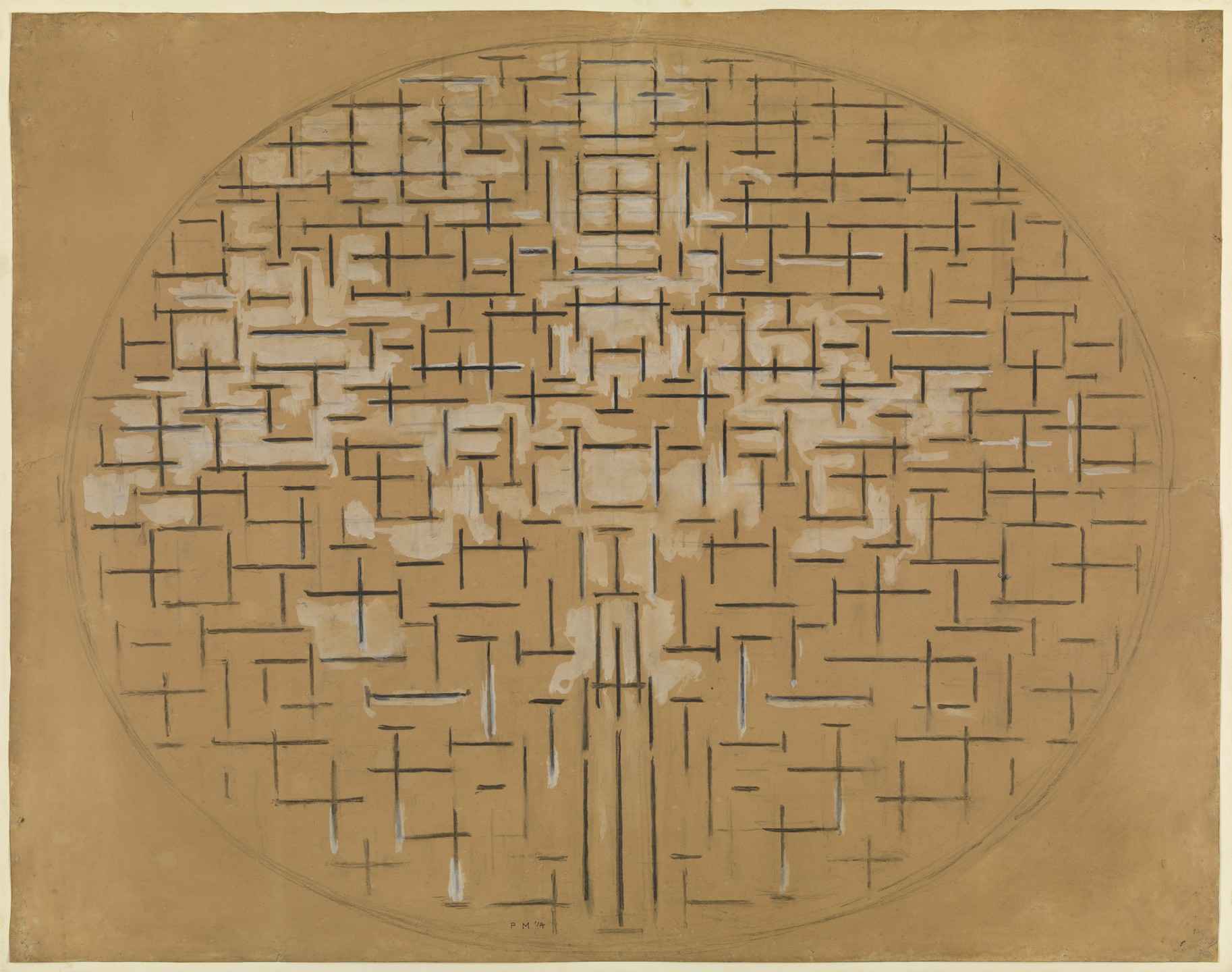

이 시기에 그에게 일어났던 변화 중 주목할 만한 것은 그가 존 케이지와 함께 다이세츠 스즈키의 강의를 들으러 다니며 일본의 미학과 선불교에 관심을 갖기 시작했다는 것이고, 줄곧 피에트 몬드리안의 플러스-마이너스 그림(몬드리안이 구상에서 추상으로 이행하는 시기에 수평선과 수직선으로만 이루어진 드로잉과 회화 연작을 계속 했는데 이를 통칭해서 플러스-마이너스 그림이라고 부른다. 이는 몬드리안 1909년 경부터 심취한 견신론 (Theosophy)의 영향이라는 것은 알려진 사실이다)을 보았다는 것이다. 거스통의 초기 추상 작업들은 몬드리안의 이 연작의 영향이 강하게 보인다.

이후 추상표현주의 화가의 반열에 들며 성공적인 커리어를 이끌어 가던 거스통은 첫 변화로부터 거의 20년 후 그는 또다시 커다란 변화를 겪기 시작한다. 공식적으로는 이 시기가 1967-68년으로 기록되지만, 이미 그 이전부터 조짐이 보이기 시작했다. 몬드리안과 모네를 연상시키던 아름다운 추상회화를 그리던 거스통의 붓질이 점점 강렬해지더니 60년대에 접어들면서 검은 사각형의 형태가 떠오르기 시작한 것이다. 이 그림들이 종종 <화가Painter>나 <두상Head>이라고 제목이 붙은 것을 보면 구체적 이미지의 등장으로 보아도 무리가 없을 것이다. 죽음 같은 답답함을 느낀 것일까? 거스통의 경력 중 큰 변화는 두 번으로 기록되지만 그는 언제나 변화가 필요한 작가였고, 변화가 작업의 추동이고 의미였다. 니체의 언어를 빌면 행위라는 것의 주의미는 변화이고, 이는 디오니소스적인 힘이다. 그는 언젠가 추상에서 구상으로 옮겨간 자신의 변화에 대해 “순환적circular”인 것일 뿐이라고, 그냥 계속해서 살아가는 것일 뿐이라고 했다.

“나는 내 앞에 길이 있는 걸 알아요. 그 길은 매우 거칠고 다듬어지지 않은 길이에요.”

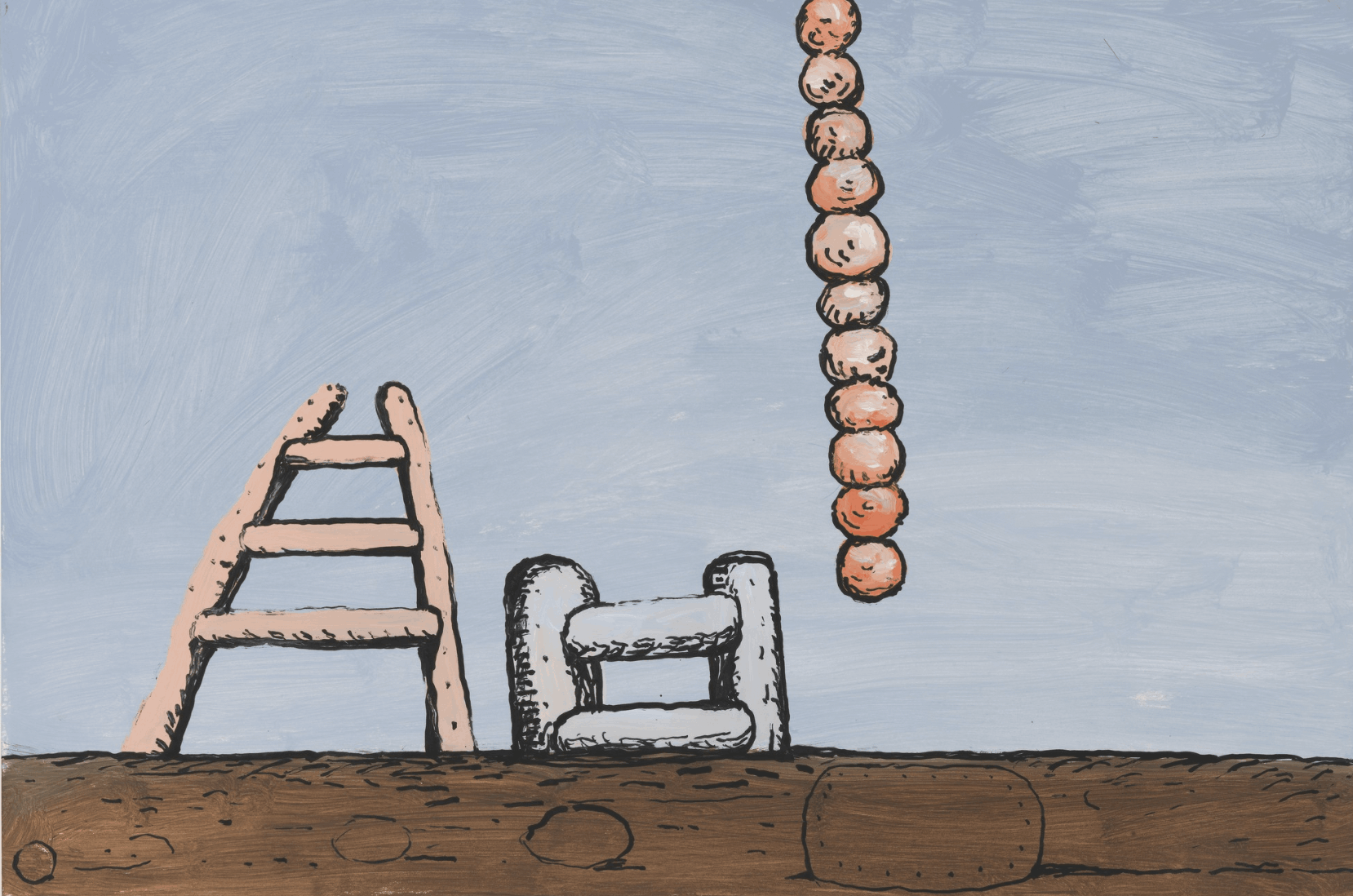

1967년 맨해튼에 있던 작업실을 정리하고 뉴욕 주 우드스탁으로 이사간 거스통은 마치 언어를 발견하는 어린 아이처럼 선부터 그리기 시작한다. “그림을 한번도 본 적이 없는” 사람처럼 선을 그리고, “물건들을 처음 보듯이” 주변의 사물을 그리기 시작했다. 그가 당시 그린 책, 도시, 구두, 시계 등은 새로운 언어처럼, 글씨처럼, 그만의 서예처럼 느껴지고, 동시에 그 형태는 폭탄이 터져도 깨지지 않을 것 같은 단단함이 있었다. 그가 그린 모든 것이 새로운 형태로 태어났고, 그렇게 존재할 뿐 그 외엔 아무 의미도 필요하지 않았다.

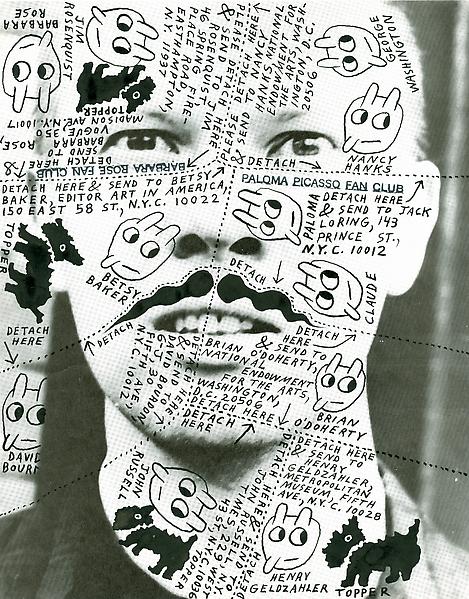

어린 아이가 더듬더듬 말을 배우듯 새로운 언어로 그림을 그렸기에 그가 그린 사물들이 서투르게 보였을까. 그가 11, 12살 처음으로 그림을 그리기 시작할 무렵, 주로 신문에 난 만화cartoon를 베껴 그렸고, 후에는 로스앤젤레스의 쥬니어 타임즈에서 개최한 대회에서 만화로 상까지 받기도 한다.(만화가 갖는 팝적인 의미때문에 그가 후기의 이미지를 그리기 시작한 이후로 많은 친구를 잃었다. 추상표현주의자들은 팝아트를 혐오했다.) 만화는 종종 의도적인 서투름과 과장으로 유머를 자아낸다. 구상과 추상회화를 모두 섭렵한 그가 어린 시절 그리던 그 서투름과 과장의 세계로 돌아온 것이다. 그는 이즈음 이렇게 묻곤 했다.“이건 아주 오래된 석판 같지 않아요?” “고대의 필사본 같지 않아요?” 새로운 형태를 찾으면서 자신의 어린 시절은 물론, 더 오래된 형태들을 떠올린 것이다.

“정말 그림을 그릴 때는, 그림을 그리는 사람마저 없어지죠.”

그가 처음 그림을 그리기 시작한 것은 그가 아버지의 자살을 목격하고 얼마 지나지 않아서였다. 러시아계 유태인인 거스통의 부모는 우크라이나 오데사에서 유태인 박해를 피해 캐나다 몬트리올로 이민왔다. 거스통이 1913년 몬트리올에서 태어났고, 1922년 그의 가족은 다시 미국 로스앤젤레스로 이주한다. 철도 기술자였던 거스통의 아버지는 LA에서 직업을 구하기 힘들었고 넝마주이를 하다가 23년 목을 메어 자살한다. 죽은 아버지를 발견한 것은 당시 열 살이던 거스통이었다. 비극은 여기서 멈추지 않았고, 32년에는 그와 가깝던 형이 자동차 사고로 다리를 다쳐 세상을 떠난다. 그가 끊임없이 고물, 쓰레기가 흩어져있거나 쌓여있고, 다리와 구두가 잔뜩 겹치고 쌓인 이미지를 그리는 것은 우리에게 해석하라고 유혹하는 듯하다.(홀로코스트와의 연관성도 자주 언급된다) 거스통은 그림을 완성할 때마다 죽음을 떠올린다고 했다. 그리고 연속성에 대해 자주 말했다. 그림을 새로 그리는 것은 새로 태어나는 것이었고, 계속해서 살아가려면 변화해야 했고, 거듭해서 태어나야 했다.

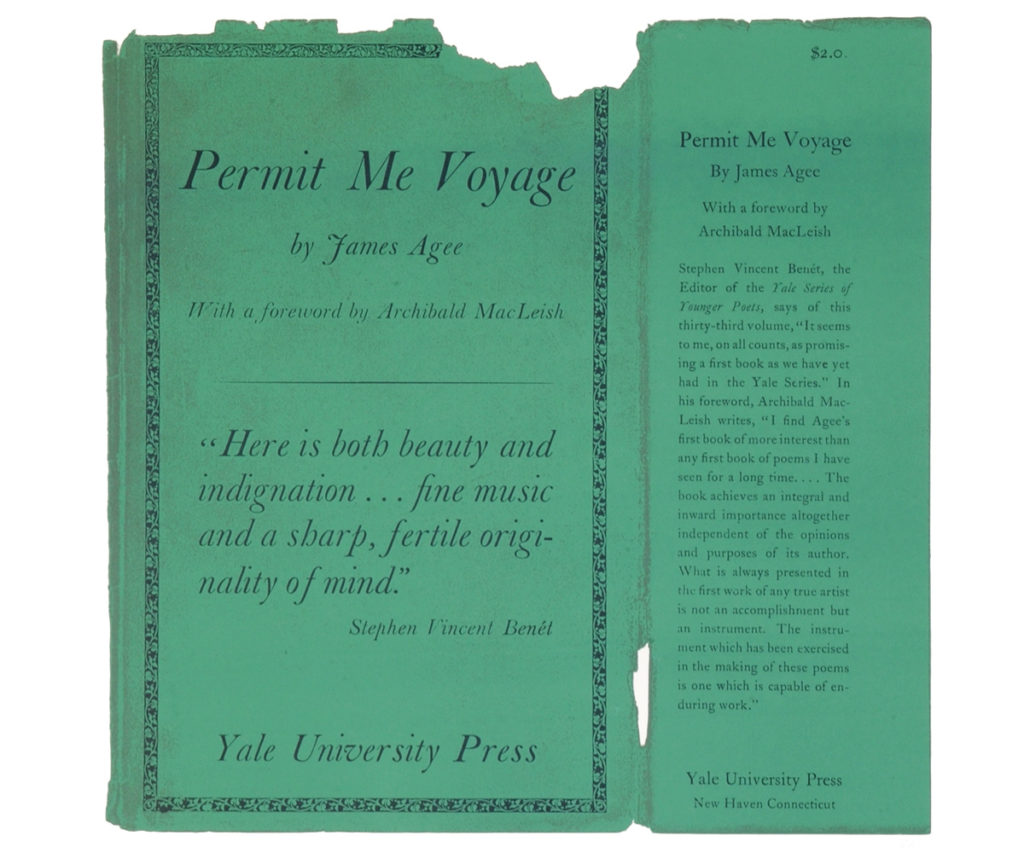

40년 이상을 해로한 거스통의 부인은 시인이었고, 거스통은 시인 친구들을 가까이 했다. 그 역시 끊임없이 시를 읽었고, 시의 영향을 받기도 했다. (2017년 이탈리아 베니스에서 평생에 걸친 거스통의 시와 시인과의 관계를 통찰하는 전시, “필립 거스통과 시인들”이 열렸다.) 그의 후기 작품들을 보면 유적처럼, 고물처럼, 구두와 나무토막, 다리, 시계, 붓, 그림들이 잔뜩 쌓여 있고, 나중에는 사다리가 자주 등장한다. 이 이미지들은 W B 예이츠의 <서커스 동물의 탈주>의 마지막 연과 놀라울 정도로 유사하다. 예이츠도 이 시에서 늙고 병들면서 사라지는 시적 영감에 대한 한탄, 그리고 끝이 곧 시작이라는 암시를 담았다.

순수한 머릿속에서 자라나 완성된

그 위대한 이미지들은 도대체 어디서 비롯되었는가?

고물 한 더미, 또는 쓸어모은 거리의 쓰레기

낡은 주전자, 낡은 병들, 부서진 캔,

낡은 철물, 낡은 뼈다귀, 낡은 천조가리,

돈통을 지키려 발광하는 창녀들,

이제 내 사다리가 없어지고 말았으니

나는 모든 사다리가 시작하는 곳에 누워야겠다.

마음 속 낡은 고물 가게 안에서

역시 예이츠가 쓴 시 <비잔틴 1930>의 “삶 속에 죽음, 죽음 속의 삶”이라는 구절처럼 그는 어쩌면 삶과 죽음이 뒤섞인 공간에 있었다. “밤낮없이 일한다”는 것은 몰입을 의미한다. 창작하는 대상과 가장 가까이 있을 때, 그 공간 속에 들어가있을 때가 가장 삶에 가깝고, 동시에 가장 죽음에 가까운 상태가 아닐까. 모든 것의 의미가 사라지고, 모든 것을 내려놓는 그 순간, 비로소 새로운 형태가 태어난다.

I learned the expression “working around the clock” when I was reading Night Studio: A Memoir of Philip Guston. I was still in my late twenties or early thirties. It is a book by Philip Guston’s daughter, Musa Mayer, who grew up watching her father and wrote about him and his life as a whole, including family relations as well as his oeuvre. It is said in the book that Guston, who had been painting these beautiful abstract paintings and leading successful career, suddenly went through a transformation from 1967 and devoted himself to work day and night like a crazy person. He drew nonstop, and started to draw and paint the objects around him one by one. Like a child learning to speak, he drew things in a new language he discovered. Among the objects, there was a clock and a lightbulb. The title of the book is also “Night Studio”(Guston often worked through the night). The phrase “Working around the clock” remained with me.

After reading this book and seeing more works of his, Guston became an important artist to me. There are several reasons for this. His early figurative work with its influence of Giorgio de Chirico and Piero della Francesca–who were already important artists to me then– his early abstract paintings evoking Mondrian’s plus and minus series with short, trembling red brush marks like fresh wounds, and the shocking late works with violent and powerful poetry within. They all have their own places in my mind. Above all, however, the biggest reason why he became important to me is the “transformation” itself and the works that emerged from that intense process. The one or two lines he drew, a bent line, a curved line, shortly cut lines, and a circle that seemed to be drawn with hesitation. The simultaneous bareness and fullness I feel in those drawings was almost shocking. The forms of objects, books, watches, shoes, and cities that were then revealed were both primitive and solid. They were raw and clumsy, but seemed to be crystallized like a loaded word. They were dumb looking forms but also felt wise, looked ancient but were definitely something I had never seen before.

“I wanted to see what would happen if I just started painting again almost from scratch.”

The first transformation in Guston’s practice was around the time his colleagues all went through significant shifts to abstraction. Guston was an artist who drew based on thorough sketches and plans like Renaissance artists, but he felt the urge to start everything anew from the beginning. His main methodology of painting had to change. He even set a rule, to “complete a painting without stepping back to look at it.” To say that you won’t stand back and look at your painting means to give up your judgment, that you’re going to draw without looking at the resulting image. It means to let go of the ability to draw and paint that has been learned and cultivated thus far, the knowledge and control to compose a painting, and the ego that judges one’s own painting. He abandoned everything to be within the painting to be more “involved” in it. (He once changed the word “happy” to “involved” in an interview. For him, happiness was to be “involved” at least when he paints.)

Two things to note that happened to him during this period were that he became interested in Japanese aesthetics and Zen Buddhism while attending Daisetsu Suzuki’s lectures with John Cage, and kept looking at Mondrian’s plus and minus paintings. (during Mondrian’s transition from figuration to abstraction, he made a series of paintings and drawings using horizontal and vertical lines, and called it plus and minus paintings. It is known that this series was influenced by his deep interest in Theosophy since around 1909). Guston’s early abstract works appear to have been strongly influenced by Mondrian’s paintings of this series.

After that, Guston, who was by then in the ranks of major abstract expressionists, began to undergo another transformation almost 20 years later. Officially, this period is recorded as 1967-68, but signs had already begun to appear before then. The brush strokes of Guston, who had been drawing haunting abstract paintings reminiscent of Mondrian and Monet, became increasingly intense, and in the 60s, a black square began to emerge. Given that these paintings are often titled Painter or Head, it would not be unreasonable to see them as specific images. Did he feel a frustration that appears a dark block hovering right in front of him, or was he himself turning into one? Two major changes are recorded in Guston’s career, but he was an artist in need of constant change which was the driving force and meaning behind his work. In Nietzsche’s language, the primary meaning of action is change, and this is a Dionysian power. He said that his shift from abstraction to figuration was merely “circular,” and that he was simply continuing to be alive.

“I knew ahead of me a road was lying. A very crude, inchoate road.”

Guston, who cleaned up his studio in Manhattan in 1967 and moved to Woodstock, New York, began drawing lines as if he was a young child discovering language for the first time. He drew lines like a person who had “never seen a picture before”, and drew objects around him as if he had “never seen things before.” The books, cities, shoes, and watches he drew at the time were like his own made-up calligraphy, and at the same time, the forms had a solidity that could not be broken even if a bomb exploded. Everything he painted was born in a new form, with such presence; no other meaning or narrative was needed.

Did the objects he painted look clumsy because he rendered them in a new language as if a young child were stuttering and learning to speak? When he first began painting at the age of 11 or 12, he copied newspaper cartoons, and later even won a cartoon award at a competition held by Junior Times in Los Angeles. (Because of the Pop nature of cartoons, he lost many friends since he’d gone through this transformation. Abstract Expressionists would refuse to be in one room with Pop artists.) Cartoons often evoke humor with intentional clumsiness and exaggeration. Having mastered both representational and abstract painting, he returned to the world of clumsiness and exaggeration he had painted as a child. He used to ask around this time, “doesn’t that look like an old stone tablet?” “Isn’t this like an ancient manuscript?” Searching for a new form, he revisited his childhood and imagined much older forms in his mind.

“If you are really painting, YOU walk out.”

It wasn’t long after he witnessed his father’s suicide that he first began drawing seriously. Guston’s parents, who were Russian Jews, immigrated from Odessa, Ukraine to Montreal, Canada to escape vicious treatment of Jews. Guston was born in Montreal in 1913, and his family moved again in 1922, this time, to Los Angeles, US. Guston’s father, who used to work as a machinist in railway, had a hard time finding a job in LA and worked as a junkman and committed suicide in 1923. It was Guston, who was 10 years old at the time, who discovered his dead father who hung himself. The tragedy did not stop there, and in ’32, his brother Nat, who was close to him, died from a car accident in which his legs were crushed. He painted over and over again images of old and useless things scattered nonsensically or piled up, and huge blocks or piles of shoes and legs. Is he challenging us to interpret or analyze?(It is often discussed that these images provoke an association with the Holocaust.) Guston said that every time he completed a painting, it felt like death to him. And he often talked about continuity. To him, painting a new work was to be born anew, to change to continue living, and to be born repeatedly.

Guston’s wife of more than 40 years, Musa MccKim, was a poet, and he had close poet friends. He constantly read and wrote, often painting in relation to what he read and pictured in poems. (There was an exhibition in 2017 in Venice, Italy investigating his lifelong relationship with poets and poetry called Philip Guston and the Poets.) In his later works, like ruins and junk, shoes, wooden pieces, legs, watches, brushes, and paintings are piled up, and later ladders often appear. These images are surprisingly similar to the last part of W B Yeats “The Circus Animals’ Desertion(1939)”. In this poem, Yeats also lamented about poetic inspiration disappearing as he grew old and sick, but implied that the end was the new beginning.

Those masterful images because complete

Grew in pure mind but out of what began?

A mound of refuse or the sweepings of a street,

Old kettles, old bottles, and a broken can,

Old iron, old bones, old rags, that raving slut

Who keeps the till. Now that my ladder’s gone

I must lie down where all the ladders start

In the foul rag and bone shop of the heart.

Like the phrase “death in life, life in death” written by Yeats in “Byzantium(1930)”, in his entire life, he was most likely in a space in which life and death merged. The fact that you work around the clock means you lost yourself in something; you lose track of time. When you are immersed like that, when you are closest to what you create and are completely present in that space, isn’t that when you are closest to life, and at the same time, closest to death? It is that moment, when everything loses its meaning, you let go of everything, and a new form is finally born.

RELATED POSTS