윤형근의 전시장에서

Between Umber and Ultramarine : At the Exhibition of Yun Hyong Keun

Text and translation by 박상미 Mimi Park

데이빗 즈워너 갤러리에서 윤형근의 전시를 오픈하던 날 토크가 있었다. 한 평론가가 관객을 이끌고 갤러리를 돌며 윤형근의 작품 세계에 대해 이야기하는 방식이었다. 토크 중 윤형근의 말을 인용했다.

“나는 그림에 답은 없다고 생각한다. 나는 무엇을 그려야 할지, 또 언제 그만 그려야 할지 잘 모르겠다. 거기서, 그 불확실함 가운데서 나는 그저 그린다. 마음 속에 정해놓은 목표는 없다. 나는 아무것도 아닌, 그 무엇을 그리고자 한다. 그것이 나를 끝없이 나아가게 한다.”

그 평론가는 그 말이 새무얼 베케트를 연상시킨다고 했다. 정말 그랬다. 한국어로 들었다면 그동안 흔히 들어온, 어느 단색화 화가라도 할 만한 얘기라 생각했을 것이다. 그런데 영어로 번역한 문구를 들으니 베케트의 부조리한 문장들이 생각나는 것이 사실이었다.

우선 윤형근의 말은 베케트와 조르쥬 뒤투이트가 주고 받은 서신의 일부를 발췌한 짧은 대화록 <세 가지 대화>의 내용을 연상시킨다. 이는 세 사람의 화가, 피에르 탈-코트, 앙드레 마송, 브람 반 벨데를 놓고 베케트와 뒤투이트가 주고 받은 대화를 기록한 것인데, 베케트는 이들을 논하는 듯하면서 창작에 관한 자기 자신의 고민을 드러낸다. 탈-코트에 대해 논하는 부분에서 그는 “표현할 것이 없는 상태, 표현할 재료도, 표현할 소재도, 표현할 힘도, 표현할 욕망도, 표현할 의무도 없는 상태를 표현하는 일”에 대해 말한다. 과거의 예술보다 더 잘 할 수 있다거나, 진실이나 아름다움을 표현하겠다는 야심찬 태도가 아닌, 표현할 것이 없는 상태가 출발점이고 표현할 수 있는 대상이라고 한 것이다. 그리고 베케트의 소설 삼부작(<몰로이>, <말론 죽다>를 포함한)의 마지막 편인 <이름 붙일 수 없는 자> 는 “나는 계속할 수 없어. 나는 계속할 거야. I can’t go on, I’ll go on” 라는 문장으로 끝을 맺는데, 윤형근의 말은 이 유명한 문장을 또한 연상시킨다. 이 문장은 베케트 식 글쓰기의 전형을 예로 들때 자주 인용된다. 갈 수 없다고 해놓고는 바로 또 갈 거라고 말하는 것은 논리적으로 앞뒤가 맞지 않는 것처럼 들리지만, 어쩌면 우리 모두가 처한 역설적인 상황이라는 것을 곧 깨닫게 된다. 이 두 가지 예는, 즉 예술가의 ‘표현할 것 없음’을 선언했다는 점, 그리고 말이 안 되는 것처럼 들리는 역설을 공공연하게 표현 방식으로 사용했다는 사실은 베케트가 남긴 문학적 족적을 잘 요약해준다.

베케트가 그의 작품 세계를 이루게 된 경위에 대한 유명한 일화가 있다. 베케트가 파리의 한 대학에서 강사로 일할 때 제임스 조이스를 만났고 조이스와의 만남은 베케트에게 큰 영향을 미친다. 베케트는 조이스의 <피네간의 경야>의 집필을 위한 리서치를 돕기도 하며 오랜 세월 그와 가깝게 지내게 된다. 그러던 중 베케트가 잠시 더블린에 다니러 갔을 때 그는 그의 엄마의 방에서 갑작스런 깨달음을 얻게 된다. (이후 집필한 그의 소설 몰로이Molloy의 도입 부분은 엄마의 방이 배경이 된다.) 그는 계속 이런 식이라면 평생 조이스의 그늘에서 벗어나지 못할 것이고, 이제는 다른 길을 걸어야 한다고 깨달은 것이다. 즉, 조이스가 ‘더 많이 아는’ 방향으로 가고 있고, 언제나 뭔가를 ‘더하는’ 식의 작업을 하고 있다면 자신은 그 반대, 즉 자신의 무지와 무능을 인정하고 ‘모른다’라는 사실을 큰 전제로, 더하기가 아닌 빼기 식의 가난한 작업을 자신의 과업으로 삼아야 한다고 느낀 것이다. 그동안 서구의 의식 속에서는 용납되지 않던 ‘모른다’는 전제를 의식적인 하나의 방법론이자 태도로 삼은 것이다. 그는 또한 영어가 모국어이었음에도 불구하고 불어로 글을 썼는데, 불어로 써야 스타일이 없는 문체로 쓰기가 용이하다고 생각했기 때문이었다. 그렇다면 무엇을 그릴지 모르고, 목표가 없고, 아무 것도 아닌 것을 그린다는 윤형근의 말도 하나의 방법론이었을까. 어디선가 접점이 있는 듯 보이는 베케트와 윤형근의 정신 세계는 비교가 가능한 것일까.

노자는 <도덕경>의 첫째 장에서 “도가 말해질 수 있으면 진정한 도가 아니고,/ 이름이 개념화될 수 있으면 진정한 이름이 아니다./ 무는 이 세계의 시작을 가리키고,/ 유는 모든 만물을 통칭하여 가리킨다. 언제나 무를 가지고는 세계의 오묘한 영역을 나타내려 하고,/ 언제나 유를 가지고는 구체적으로 보이는 영역을 나타내려 한다…….” 고 했다. 노자는 도를 ‘무엇’이라고 정의하지 않는다. 그보다는 무와 유의 대비를 통해, 그 대비되는 관계 속에서 형성되는 것이라고 말하고 있다. 유가 있으면 무가 있는데 그 관계 속에서 세상을 파악할 수 있다는 것이다. 베케트가 자신의 방법론을 깨닫고 정립한 것도 ‘더 알고자’하는 세상을 향한, 그 반대편의 존재를 알리는 선언이었다. 노자의 ‘무’가 서양 철학에서 말하는 ‘절대무’의 상태가 아니라 유에 상대하는 ‘비어있는’ 상태에 가까운 것처럼, 베케트의 ‘모른다’는 언명 또한 그가 실제로 아무 것도 모르는 것이 아니라 ‘모른다’는 태도를 통해 경험하는 세계의 ‘오묘함’을 전하고, 궁극적으로는 그 반대편의 세상과 만남을 꾀한 것이었다. 윤형근의 전시 토크에서 누군가 그런 질문을 했다. 아무 것도 의도하지 않았다면 어떻게 그림을 그린다는 행위가 가능하냐고. 윤형근이 ‘의도하지 않는다’고 한 것은 그림을 그려야 한다는 의도 자체가 전혀 없는 ‘절대무’의 상태라기 보다, ‘비어있는’ 상태에서 그림에 접근하겠다는 말과 같을 것이다. 이는 윤형근 뿐 아니라 다른 단색화 작가들의 접근 방식이기도 했다.

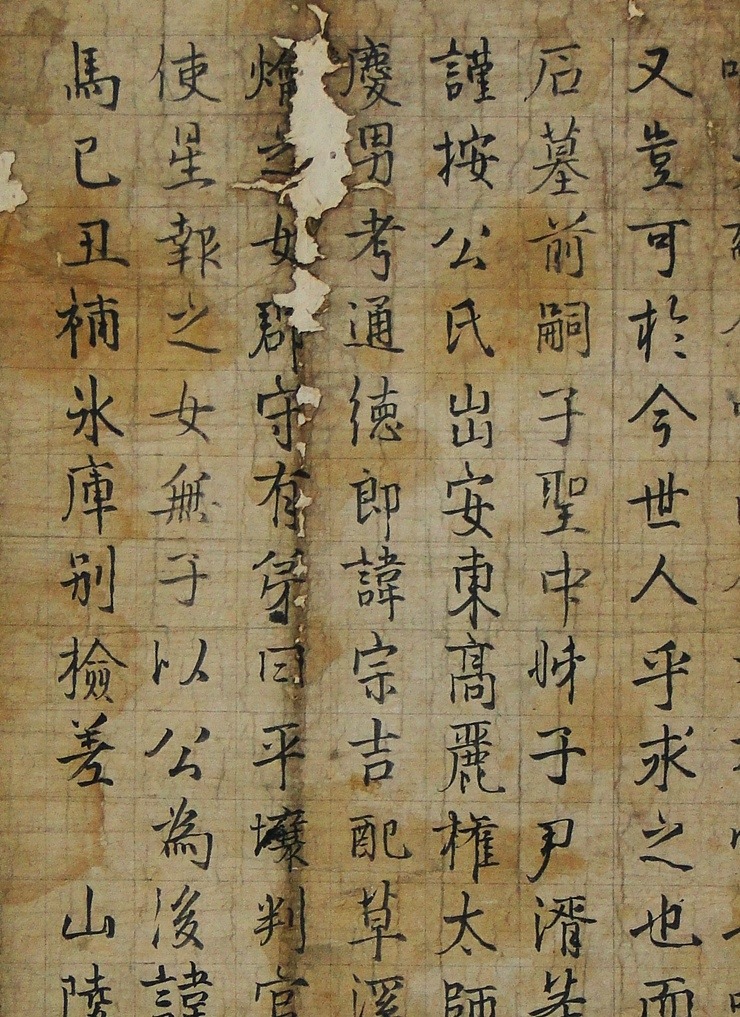

언젠가 나는 단색화의 특징을 크게 두 가지가 있다고 쓴 적이 있다. 반복적 액션과 물성의 희박화가 그것이다. 그 중 반복적 액션에 대해 말하려면 한국의 선비 문화에 대해 이야기하지 않을 수 없다. 한국인의 정신 세계는 주로 유불선 (물론 샤머니즘도 빼놓을 수 없다)의 영향이 고루 섞여진 형태로 나타나는데(시대마다 주된 사상은 달라지지만) 이 세 종교에서 모두 자기 수양(수신, 몰아, 무위)이 매우 중요한 가치이자, 방법론, 그리고 궁극의 목표가 된다. 한국의 선비들은 매일 글을 읽고 쓰는 일을 되풀이했는데, 그 목표는 단순한 지식의 축적보다는 유불선에서 최고로 치는 경지에 도달하기 위함이었다. 한국의 선비들은 일찌기 지식을 쌓으면 이를 버릴 줄 알아야 하고 소유와 동시에 무소유를 생각했고 자신을 잊는 행위를 통해 명징한 정신 세계에 도달하려 했다.

이에 도달하기 위한 방법으로 선비들은 매일 반복해서 글을 읽고 또 썼다. 선비들의 글쓰기인 서예는 먹을 갈아 한지 위에 붓으로 글씨를 쓰는 행위를 말하는데, 선비들은 자신의 글 뿐 아니라 이미 있는 싯구나 문장을 썼다. 선비의 서예는 (서양의 글쓰기와 비교되는) 두가지 중요한 특징을 갖는다. 첫 번째는 글씨를 쓰는 행위 자체가 신체의 자세와 움직임에 그 중요한 근거를 두고 있어 어떤 자세로 어떻게 글을 쓰느냐가 서체를 낳는 중요한 요인이 된다는 사실이다. 동양의 서예는 이런 관점에서 보면 쓰기와 그리기를 합친 형태로 볼 수 있는데, 서양의 쓰기는 물론 그리기와도 많은 차이가 있다. 서양의 전통적인 쓰기와 그리기에서는 애초부터 신체성이 대체로 배제된 반면 서예에서는 어떤 몸과 마음 가짐으로 서예에 임하느냐가 기본이었다. 몸을 바로 하고 마음을 비운 상태에서 그리는 선의 결과가 서예인 것이다. 두 번째는 선비의 글씨란 선비의 인격이, 그 수양의 정도가 시각적 스타일로 승화되는 지점으로 볼 수 있다는 것이다. 영어에서 인격을 뜻할 수 있는 말로 personality나 character같은 단어를 생각할 수 있지만 이는 개인이 갖는 특질에 더 가깝지 한 개인이 성취할 수 있는 덕이나 품격의 정도를 나타내주지는 않는다. 바로 이 지점이 서양에서 윤형근의 회화나 단색화를 이해하기 힘들게 하는 측면이다. 베케트와 윤형근의 접점이 있다해도 아마도 이 부분에서 그 성격이 달라질 것이다.

윤형근은 반복해서 자신의 그림이 추사 김정희 글씨에서 비롯되었다고 말했다. 짐작할 수 있듯이 윤형근의 이 말은 자신의 그림이 한국의 서예와 수묵화 전통에서 온 것이며, 그림을 그릴 때의 몸과 마음이 동떨어진 것이 아니라는 의미일 것이다. 높은 인격을 갖는다는 것은 단순히 착한 마음으로 그 시대가 요구하는 도덕에 맞게 사는 것이 아니다. 고결한 인격의 성취는 몰아, 무위를 통한 마음의 평정 상태를 갖는 것을 바탕으로 한다. 명상을 할 때 생각을 없애고 자아를 잊어야 비로소 현재에 존재할 수 있는 것처럼, 고결한 인격도 욕망과 의도와 집착과 취향을 모두 잊고 방 한가운데 정지한 촛불처럼 세상의 숨결에 흔들리지 않는 마음의 상태를 필요로 한다.

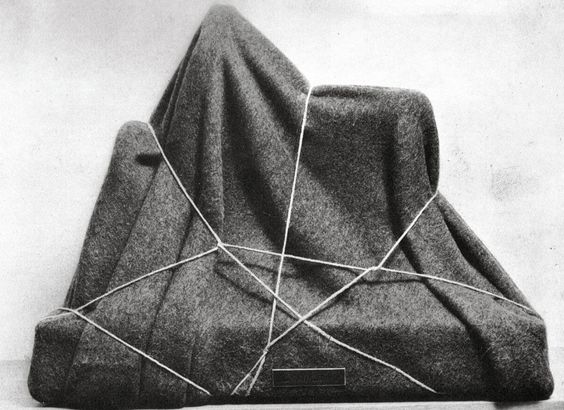

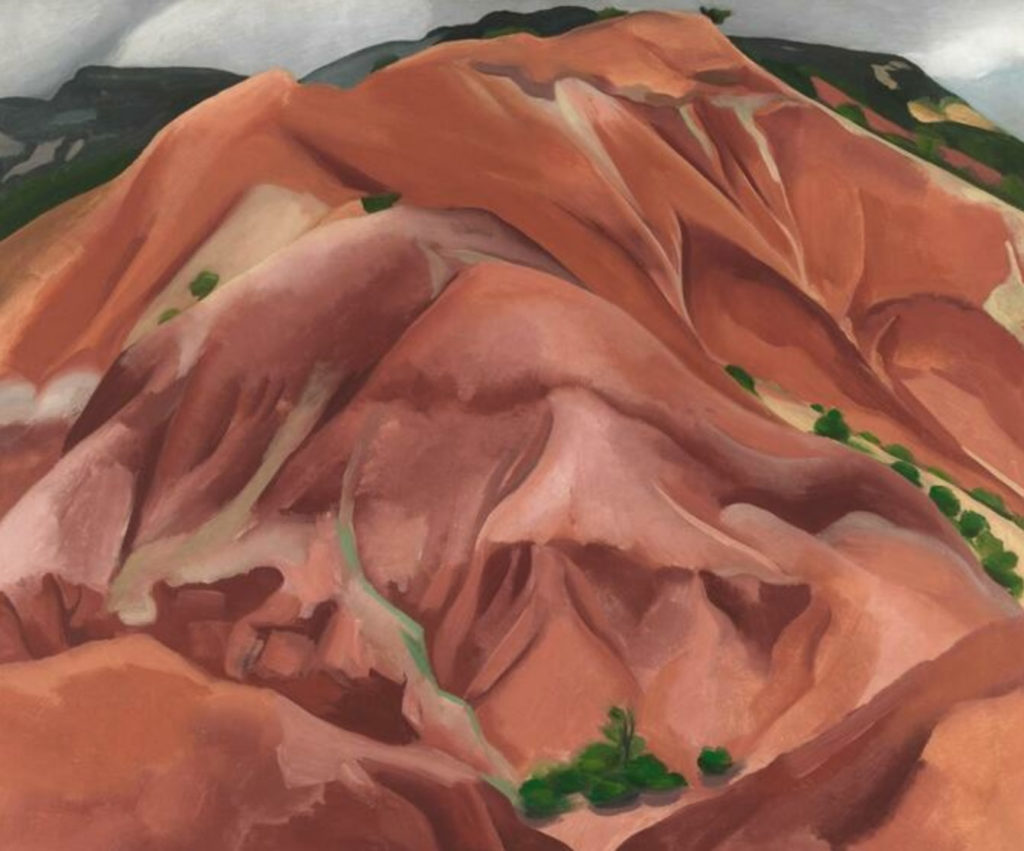

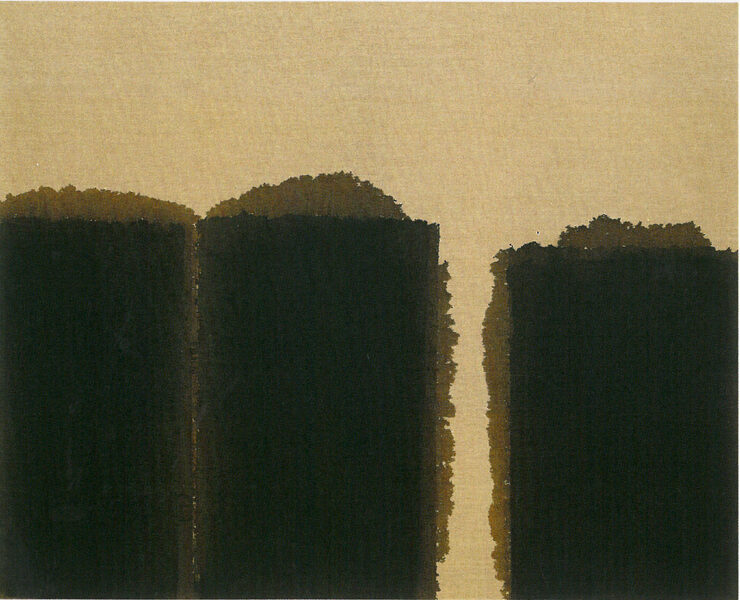

이러한 전제에서 출발하는 윤형근의 회화는 반복되는 액션을 통한 반복적 패턴을 낳는 방식보다는(박서보, 정상화 등의 회화에서 보이는) 반복적인 액션과 형태가 모두 감추어지는 방식을 택한다. 물감을 계속해서 덧칠하는 그의 액션은 물감이 더 깊고 어두운 색감으로 캔버스에 스미는 효과를 낳는다. 상반되는 두 개의 색–엄버와 울트라마린–으로 깊고 어두운 색을 만든 그의 화법 속에도 상반되는 관계 속에서 화면 위의 이치를 파악하려 한 그의 노력을 엿볼 수 있다. 그는 그림은 이런 것이다라고 말하지 않고 그림은 무엇인지 모른다고 했다. ‘모른다’라는 겸허한 선언을 통해 서양의 이원론을 극복하고 추사의 스타일까지 뛰어넘는 ‘오묘한’ 경지에 이른 것이다.

After quoting Yun, the critic mentioned that it sounded like Beckett. Indeed. If I had listened to the quote in Korean, it could have sounded like a statement from any Dansaekhwa artist. But when I heard it translated in English, it did remind me of Beckett’s absurd phrases.

There is a paragraph in Three Dialogues in fact, the correspondence between Samuel Beckett and Georges Duthuit, that seems to be a parallel to Yun’s words. In this short, charming dialogue (where Beckett would “exit weeping” at the end), while they were talking about issues of contemporary art, Beckett reveals his own struggle in creation. “The expression that there is nothing to express, nothing with which to express, nothing from which to express, no power to express, no desire to express, together with the obligation to express.” The last novel of Beckett’s trilogy, The Unnamable ends with “I can’t go on, I’ll go on.” which is often quoted as the typical Beckett style. These two examples — the declaration of the artist that has “nothing to express” and the way of delivering a paradox in such a blunt manner– summarize well what Beckett has left as his literary legacy, and also, sound as perplexing and wise as a zen conundrum.

There is an anecdote of how Beckett had developed his mature style. While Beckett was teaching in Paris, he met James Joyce. The two remained friends after Beckett helped the research for Finnegans Wake. During that time, when Beckett was back in Dublin for a short visit, he had a revelation in his mother’s room. (He begins his novel Molloy which he wrote after this visit, describing his mother’s room as the background.) Realizing that if he continues the way he had been, he would forever remain in the shadow of Joyce, Becketts writes, “Joyce had gone as far as one could in the direction of knowing more, … and he was always adding to it, …I realized that my own way was in impoverishment, in lack of knowledge and in taking away, in subtracting rather than in adding.” Deciding to take his own path, Beckett adopted the premise of “not knowing” as a conscious methodology in writing even though it was then not accepted as a valid premise in the Western mind. If so, was Yun Hyong Keun’s comment of saying that he doesn’t know what to paint, doesn’t have a goal, and paints something which is nothing, a methodology as well? Are the minds of Beckett and Yun Hyong Keun comparable to each other since they seem to have things in common?

In the first chapter of Tao Te Ching, Lao-tse said “The Tao that can be told / is not the eternal Tao / The name that can be named / is not the eternal Name. / Nothingness heralded the beginning of our world, / Being refers to all creatures. The mystery of this world is always expressed with nothingness, / The seeming concreteness of this world is always expressed with being…” Lao-tse did not define what Tao was. Instead he says that it is what is formed in the relation between nothingness and being, and their contrast. When you have something, that means there is nothing as contrast, and you can understand the world in such a relation.

What Beckett finally declared to the world of “knowing more” is the existence of the opposite. Lao-tse’s “nothingness” is not the state of “absolute nothingness” discussed in Western philosophy. Rather it is similar to the “empty” state in contrast to being. Beckett’s declaration of “not knowing” does not mean that he actually does not know anything. With the attitude of “not knowing”, he wants to convey the mystery of the world he lives in, and ultimately desires the encounter with the world on the other side. During the talk at Yun Hyong Keun’s exhibition, somebody asked a question in the same vein. If you had not intended anything, how could the act of painting be even possible? What Yun meant by saying “he does not intend” is that he would approach painting in an “empty” state of mind, letting go of all the extrinsic intentions that are not relevant to the act of painting.

I once summarized the characteristics of Dansaekhwa in two points; repetitive action and “rarefication” of materiality. To get to these aspects, I had to point out the culture of Seon Bi, Korean scholars of the past. The spiritual world of Koreans is generally a mixture of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism (with a hint of Shamanism, of course). In this mixture of spiritual traditions, self-culture through self-discipline is considered to be of the most significant value, methodology, and ultimate goal. Korean scholars before the modern era used to read (out loud) and write (calligraphy) on a daily basis. Their purest objective was to attain the utmost “level” of a person (the other objective, more practical one, would be to pass the exam to be a government official). The method in reaching the level is to be in a constant paradox; by obtaining knowledge, you gain the wisdom to discard knowledge; nonpossession is the ultimate goal even when you can’t escape from possessing; you can accomplish the lucid state of self through self-oblivion, not intending to be yourself.

In order to do so, Seon Bi would read and write (often the same phrases and sentences) everyday in repetition. The act of calligraphy consists of grinding the ink stick, having a calm mind and right posture, and writing with a brush on hanji (Korean mulberry paper). They would write their own essays or rewrite others’ poems or sentences. The Korean scholar’s calligraphy has two major characteristics compared to Western writing. First, the act of writing involves your body. The corporal position and movement would result in a certain writing style. Eastern calligraphy is a mixed form of writing and drawing/painting. Whereas corporeality is generally excluded from Western writing, Eastern calligraphy considers the corporal and mental state of the calligrapher essential. One needs to let go. Letting go of all thoughts and intentions would lead your body to move naturally. Calligraphy was the result of a disciplined but empty state of mind and body.

The second main feature of calligraphy is that it displays the sublimate of the scholar’s integrity in visual style. Integrity signifies the virtuous qualities, the ‘level’ of them that a person would attain. It is hierarchical thinking, like class. The difference is that it is something you achieve. There is no scientific standard in measuring one’s virtue, but a certain person could be considered to be in a higher position as a person over another. It could be as obvious as the fact that one is wealthier than another, but doesn’t have anything to do with one’s wealth or social status. Korean calligraphy and drawing/painting were all viewed in this respect; One’s style and virtue were not two different things, they are one.

Yun Hyong Keun often said that his painting was inspired from the calligraphy of Kim Jeong Hui (pen name: Chusa). As we can guess, his painting sprang from the tradition of Korean calligraphy and ink painting, and this would mean that when he paints, his body and mind are in one. When they talk about integrity in the Korean culture, it is not about just living up to the moral standard required of the era, with simple good intent. In order to attain integrity in its highest form, one should reach a serene state of mind through forgetting oneself and not intending. In meditation, one should get rid of thoughts and efface oneself to exist in the present. As such, lofty integrity requires oblivion of desire, intent, attachment, and taste, in order to attain the empty state of mind which does not flicker according to worldly breath, like a candlelight staying still in the middle of a room.

Yun Hyong Keun’s painting springs from such premises. He chose the method of hiding all the repetitive action and form, rather than that of making repetitive patterns by repeating certain actions (found in paintings of Park Seo Bo, Chung Sang Hwa, etc.) His action of continuously reapplying paint entails the effect of darkening the paint color on the canvas. He painted with two contrasting colors, like being in a paradox, umber and ultramarine, which deepened the color to a profound psychological state and a certain truth on the canvas. Yun says that he does not know what a painting should be or what a painting is. Yun’s humble declaration of “not knowing” may be reaching the mysterious state of painting itself.

RELATED POSTS