여름 과일이 담긴 광주리

A Basket of Summer Fruit

01

Text by 가이 다벤포트 Guy Davenport

Translation by 박상미 Mimi Park

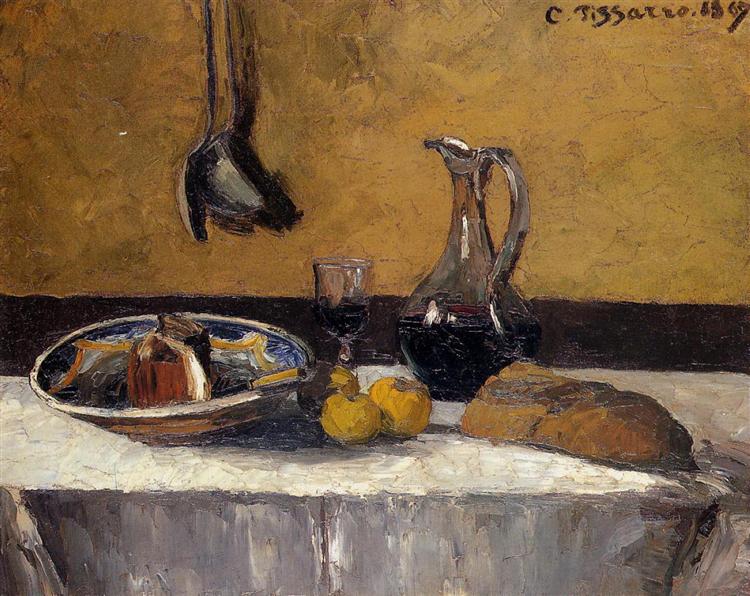

음식을 마련해서 음식을 먹기까지 그 사이에 시간이 있다. 음식이 어딘가에 놓이는 시간이다. 닭장에서 꺼내와 부엌 사이드보드에 올려 놓은 계란이나(호레이스가 살던 때의 투스카니나, 내가 어린 시절을 보낸 사우스 캐롤라이나, 요크셔어, 노르망디에서) 과수원에서 따온 사과와 배, 강에서 잡아온, 줄로 엮은 물고기들, 군데군데 피가 묻은 자고새 한 쌍, 정원에서 따온 호박과 콩이 담긴 바구니. 이들을 가르켜 17세기 중반 네덜란드 인들은 “정물 still life”이라고 이름 붙였다.

A. P. A. 보렌캠프*는 네덜란드 정물화의 역사에 대한 글에서 이 단어가 화가들이 사용하던 직업적 용어에서 왔다고 말한다. 즉 레벤leven, '살아있는' 이라는 뜻의 이 단어는 실제 모델을 앞에 놓고 그린 그림을 가리킬 때 쓰는 말로, 브라우벤레벤vrouwenleven[woman's life] 은 여자 모델과 포즈를 취할 때 이따금씩 움직여야 하는 모델을 뜻하고, 스틸레벤stillleven[still life]은 과일이나 꽃, 물고기처럼 움직이지 않고 가만히 있는 대상을 가리킨다. 이는 화가들과 딜러들이 일반적으로 사용하는 용어였다. 르네상스 네덜란드에는 정물화를 갖고 싶어하는 사람들이 역사적으로 그 어느 시대보다 많았는데, 이들이 사용한 용어들은 다음과 같았다.

*알폰수스 페트루스 안토니우스 보렌캠프 Alphonsus Petrus Antonius Vorenkamp(1898-1953)

네덜란드 태생의 미술사학자. 17세기 네덜란드 정물화에 관한 논문으로 박사학위를 받았다. 미국 매사추세츠 주 스미스 대학에서 미술사를 가르쳤고, 네덜란드로 돌아간 후에는 로테르담 등에서 미술관 관장을 지냈다.

아침식사나 간단한 스낵을 가리키는 온트비트 ontbijt[breakfast]*, 네덜란드인들이 연회 뿐 아니라 가득 쌓아놓은 갖가지 페이스트리들을 뜻할 때 사용하는 방켓banket[banquet], 초오서가 '에피쿠로스의 진정한 아들 (Epicurous owene sone)'*이라고 부른 자유 지주(The Franklin)의 화려한 식탁을 가리키는, 호화로운 프롱크스틸레벤pronkstillleven [ornate still life]*이라는 말도 있다.

앞으로 살펴 보겠지만 프롱크스틸레벤은 키이츠가 "세인트 아그네스의 저녁The Eve of St. Agnes"에서 묘사한 것처럼 호화로운 것일 수 있고, 디킨스의 크리스마스 파티처럼 즐거운 것일 수 있고, 토마스 러브 피콕이 묘사한, 에피큐리언인 대지주와 기인들의 대단한 상차림처럼 코믹할 수도 있다. 또는 조이스의 "죽은 이들The Dead" 이나 에드가 앨런 포우의 작품들처럼 정교한 상징적인 목적을 가진, 홀바인의 "대사들"이나 뒤러의 "멜랑콜리아"에서 보이는 철학적이고 시적인 종류의 상징물들이 등장하는 프롱크스틸레벤이 될 수도 있다.

여기서 짚고 가야 할 것은 테이블에 차려지는 식사의 형태로서 에피큐리언의 역사이다. 에피큐리언의 식사란 역사적으로, 놀랍도록 절제된 생활을 하는 철학자의 간소한 식사를 말한다. 지금 우리도 할 수 있을 에피큐리언의 식사-염소 치즈와 빵, 그리고 차가운 샘물-는 아마도 밀턴의 유명한 야식인 파이프 담배와 차가운 물 한 잔과 비슷한 정도의 식사일 것이다. 하지만 이제 '에피큐리언' 이라는 말은 그 이름에서 기원한, 지금도 사용하는 아랍어인 '비큐로스(특히 모로코인들과 영국 성공회 목사들이 사용하던)'가 가진 의미, 즉 고급스런 생활과 호화로운 음식이라는 뜻을 갖게 되었다.

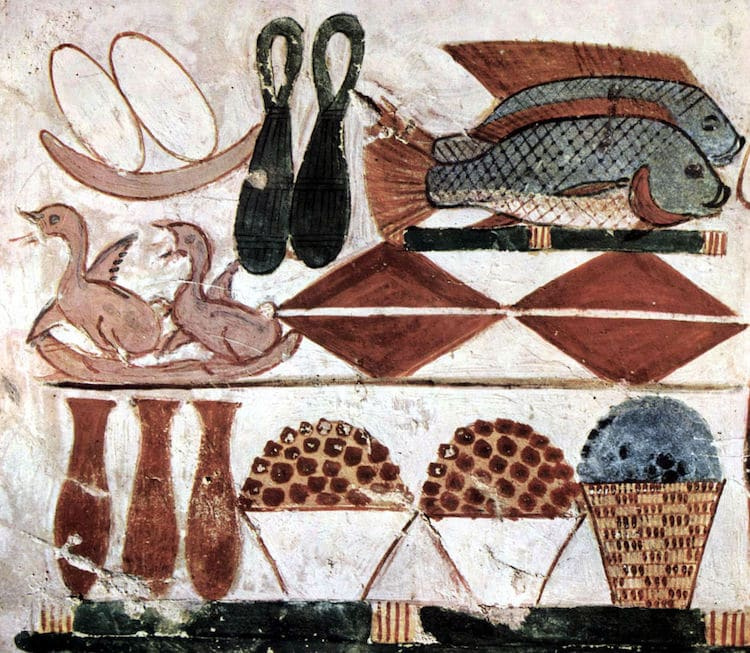

정물화는 역사적으로 두 시발점을 갖는데, 하나는 이집트고 다른 하나는 이스라엘이다. 지금까지 끊이지 않고 내려오는 두 가지 주제가 여기서 확립되었다.

고대인들은 죽은 자들에게 음식을 바쳤다. 고대의 무덤 속에선 접시와 단지가 발견된다. 이집트에서는 우리가 알고 있는 가장 오래 전부터 자손들은 돌아간 부모에게 경건하게 음식을 바쳤다. 영혼, 카 ka가 먹을 수 있도록 하기 위함이었다. 이를 나타내는 상형문자는 팔을 치켜든 모습으로, 이는 선사시대부터 숭배를 나타내는 제스처이다. 오랜 시간이 지나 선조에게 실제 음식을 바칠 가족이 없을 때, 무덤 벽에 음식 그림을 그려서 영혼이 오시리스*에게 재판을 받는 날까지, 시간이 멈출 때까지, 그리고 구원된 이집트의 영원한 7월에서 영원히 살 수 있을 때까지 그 그림 속 음식으로 연명하게 하였다.

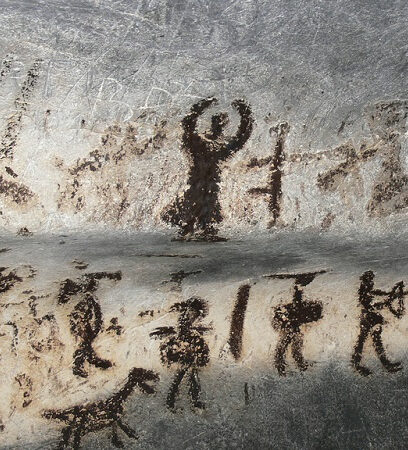

나는 이것이 정물화의 진정한 기원이라고 본다. 음식의 그림이 어떤 자양분이 될 수 있다는 완전히 원시적이고 태고적인 생각. 신석기 시대의 동굴 벽화들은 이와 비슷한 생각에 기초하고 있을 텐데, 대부분이 동물을 그린 그림이기 때문이다. 이에 대한 이론들은 모두 말이 된다. 즉 생식력을 높이기 위해 동물의 이미지를 대지의 자궁에 그렸다는 이론이나, 이미지는 실제 동물을 나타내어 그림에서 동물을 베는 장면은 실제 동물을 베게 만든다는 것이나, 더 흥미로운 이론으로 그림은 이미 죽은 동물들을 다시 살리는 행위로, 신에게 우리가 살기 위해 죽이고 먹어야 했던 동물을 바친다는 뜻이 담겨있다는 이론이 그것이다.

음식을 그리는 행위에 대한 진실이 무엇이든간에 몇 천 년에 걸쳐, 문화에 따라 그 추론은 계속 변해간다. 프란츠 카프카는 이런 우화를 들려준다.

정물화를 공부할 때 우리는 제사의 일부가 된 표범까지 미리 생각해 놓아야 한다. 정물화는 4천년 넘게 이어져 왔고 이 한 분야만을 위한 학문이 생겨도 될 정도다. 초상화는 성했다가는 쇠하고, 또는 금지되고, 또는 그 가치를 잃기도 했다.(우리 시대에 그러한 것처럼) 파우사니아스*는 그리스를 묘사할 때 초원이나 나무, 강둑이나 산의 모습은 한 장면도 묘사하지 않았다. 정물화를 제외한 회화의 모든 장르는 꾸준히 지속되지 않았고, 표현적인 예술 중에 오직 서정시나 노래만이 고대부터 남아 있는 우리 문화의 일부이다.

정물이 소재로 자리잡기 시작한 또 하나의 시발점은 아모스서에서 나온다. 기원전 8세기 선지자였던 아모스는 여로보암 2세와 동시대 인물이었다. 그가 다스리던 이스라엘 왕국이 혼란에 빠지고 붕괴될 무렵 무화과 나무를 돌보는 과원지기이자 양치기였던 아모스는 하나님으로부터 계시를 받는다. 아모스서 8장 1-2절을 보면 이렇다.

*한 손에 머리를 괸 채 생각에 빠져있는 천사의 모습은 전통적으로 멜랑콜리를 나타내는 포즈이다. 그림 속 정물은 르네상스 예술가의 과학적, 창조적 소명을 상징하는 기하학적 형태의 물건들(다면체, 구), 기구나 도구들(저울, 대패, 못 등) 그리고 멜랑콜리를 상징하는 물건들, 사다리, 모래시계, 열쇠와 주머니 등으로 이루어져 있다.

Between the gathering of food and its consumption there is an interval when it is on display. To this arrangement of eggs on the sideboard, as may be, brought in from the henhouse (in Tuscany in the time of Horace, in the South Carolina of my childhood, in Yorkshire, in Normandy), apples and pears from the orchard, a string of fish from the river, a brace of partridges flecked with blood, a basket of squash and beans from the garden, the Dutch gave the name still life around the middle of the seventeenth century.

xA. P. A. Vorenkamp tells us in his history of Dutch still life that the word comes from the jargon of painters: leven, "alive," for drawings made from a model. A vrouwenleven was a female model, and one who, from time to time, while posing, needed to move; a stillleven-fruit, flowers, or fishremained still. This was a general term, used by painters and dealers. People who fancied still life for their walls, of whom there were more in Renaissance Netherlands than at any other time in history, used such designations as ontbijt, breakfast or snack; banket, by which the Dutch mean not only our banquet but a copious array of pastries; or the sumptuous pronkstillleven, an ostentatious table such as Chaucer gives the Franklin, who was "Epicurus owene sone":

The pronkstillleven, as we shall see, can be used to voluptuous ends, as by Keats in "The Eve of St. Agnes," or to joyous ones, as with Dickens's Christmas feasts, or comic ones, as with the grand spreads laid out by Thomas Love Peacock's epicurean squires and eccentrics, or to elaborately symbolic ends, as with Joyce in "The Dead" or Edgar Allan Poe-with another kind of pronkstillleven, of philosophical and poetic emblems such as we find in Holbein's Ambassadors and Durer's Melencolia.

Epicurean, let us note, has its own history as a kind of table fare. Historically it should mean the simple meal of a philosopher of admirable restraint: an actual meal of Epicurus comes down to us-goat cheese, plain bread, and a pitcher of cold spring water-equaled, perhaps, by Milton's heroic late-night refreshment of a pipe of tobacco and a glass of cold water. But "Epicurean" turned into the sense the Arabic word from which his name derives still has, bikouros (especially used by Moroccans of the Anglican clergy), high living and rich eating.

Still life begins in history at two points, in Egypt and in Israel, establishing two themes that will persist in unbroken tradition until our time.

Primitive peoples feed their dead. In the most ancient of graves we find dishes and cruses. From the earliest times that we know of in Egypt, food was given by pious offspring to their deceased parents: the ka, or soul, could eat. Its hieroglyph is that prehistoric and lasting gesture of praise, uplifted arms. And when, after a long time, there was no more family to feed actual food to an ancestor, there was a picture of a meal painted on the tomb wall, and the ka could survive on that until the coming forth by day, of Osiris, when time will stop, and the righteous dwell forever in the eternal July of the redeemed Egypt.

That, it seems to me, is the real root of still life-an utterly primitive and archaic feeling that a picture of food has some sustenance. Something close to this idea must have been behind the neolithic cave paintings, which almost invariably depict animals. All the theories make sense: that these animal images were drawn in the earth's womb to enhance fertility; that the image was identified magically with the animal, and that to slay the image would ensure slaying the animal; or a more engaging theory, that the images were restorations of slain animals, an offering to some god of a replacement of a part of his creation that we, to stay alive, have had to kill and eat.

Whatever the truth of picturing food, the reasoning will have transmuted, culture by culture, over the millennia. Franz Kafka tells us this parable:

In the study of still life, we must be prepared for leopards that have become a part of the ceremony. Still life persists for four thousand years, and deserves study for that alone. The portrait arises and falls away, or is forbidden, or loses significance (as in our times). Landscape is intermittent-we rarely find it even in descriptions. Pausanias described Greece without a single view of meadow or wood, riverbank or mountain. All the genres of painting except still life are discontinuous, and only the lyric poem, or song, can claim so ancient a part of our culture among the expressive arts.

The other beginning of still life, as a subject, is in the Book of Amos. A prophet of the eighth century B.c., Amos was a contemporary of Jeroboam the Second (783-741), after whose reign the kingdom of Israel fell into confusion and collapse. Amos, a dresser of sycamore trees and a shepherd, was given a vision by God. At Amos 8:1-2,

The King James translators put as their rubric in the margin: "By a basket of summer fruit, it is shewed the propinquitie of Israel's end."

Vanitas vanitatem and memento mori: a still life becomes a symbol of what we shall have taken from us, though at the moment it is a sign of God's goodness and the bounty of nature.

"Hear this," said Amos, "O ye that swallow up the needy, even to make the poor of the land to fail, saying, When will the new Moone be gone, that we may sell corne? and the Sabbath, that we may set forth wheat, making the ephah small, and the shekel great, and falsifying the balances by deceit? that we may buy the poor for silver, and the needy for a pair of shoes … ?"

To the vision of the basket of summer fruit the Lord adds one of Himself upon a wall made by a plumb line, with a plumb line in His hand.

Plumb line, anakk; grief, anaqah. Summer fruit, qayits, an ending, qaits. We shall see that the still life likes puns and double meanings, as in Amos's rhetoric.

If greed, rapacity, and selfishness are the opposite of the grace of a basket of summer fruit, Amos gives us one of the most beautiful of hyperboles at the end of his book, where he describes what might be, if two walk together and be agreed, and man and God walk together.

That is, the basket will again be full of summer fruit. We can see that basket-filled with apples, pears, and figs-in Roman mosaics when the empire was at its most orderly and majestic; we can see it in the great renaissance of still life in the Netherlands after the expulsion of the Spanish and while the Dutch were refining the art of living to a high degree. We can see it in nineteenth-century American painting as a celebration of the land's goodness.

RELATED POSTS