죽는 자들의 초상: 데이지 영블러드

An Unsentimental Sculptor Confronts Mortality

01

Text by 존 야우 John Yau

Translation by 박상미 Mimi Park

데이지 영블러드는 1979년, 그녀가 30대 중반일 때 뉴욕에서 첫 개인전을 가졌다. 낮은 온도에서 구운 도기를 주재료로 하는 구상 조각가인 그녀는 다작하지 않았고, 전시회도 드물었다. 반 도렌 웩스터(2021년 9월 8일—10월 23일)에서 현재 전시 중인 <데이지 영블러드: 부드러운 자비: 흙으로 빚은 초기작과 후기작>은 70년대 말 이래 그녀의 10 번째이자 이 갤러리와는 첫 전시인데, 놓치면 안 되는 전시다.

전시에는 모두 일곱 작품이 전시되었다. 갤러리 한쪽 공간에 여섯 작품이 전시되고, 로비에는 청동으로 만든, 커다랗고 매끄러운 표면의 검은 색 “고릴라(1996)”가 조각대 위에 앉아있다. 동물 조각을 하는 작가들은 많은데, 이 소재가 갖는 타자성을 완전히 이해하고 있는 작가를 생각하면 두 명이 떠오른다. 영블러드와 데보라 버터필드가 그들이다. 이들은 소재와 재료의 조합으로 이 일을 이루어낸다. 이들이 만드는 동물들은 우리가 그들과 어떻게 관계하든, 우리와 완벽하게 분리된 세상에 있는 존재들이다.

이러한 타자성은 12인치가 조금 넘는, 잿빛 조각 “작은 고릴라(2020)”에서도 묻어나온다. “작은 고릴라”를 묘사하자면, 자존감 있고, 엄격하고, 자족적이고, 무섭고, 강하고, 무게 있어 보인다, 고 인격화시킬 수 밖에 없다는 걸 인정한다. 하지만 그 얼굴 표정은 도저히 읽을 수가 없다. 이 지점에서 영블러드의 작품이 특별한 것이다. 이 불에 구운 흙덩어리에서 뿜어져 나오는 정서를 묘사하다보면 어느 순간에 묘사할 수 있는 단어의 한계를 느끼게 되고, 이 조각과 관계 없어 보이는 무언가, 즉 따뜻하다든지 친근하다든지 하는 정서를 느끼게 될 수도 있다. 또는 이 작품의 잿빛 회색의 물질성에 집중하게 되고, 물질성으로 인해 일어나는 정서에 집중하게 될 수도 있다.

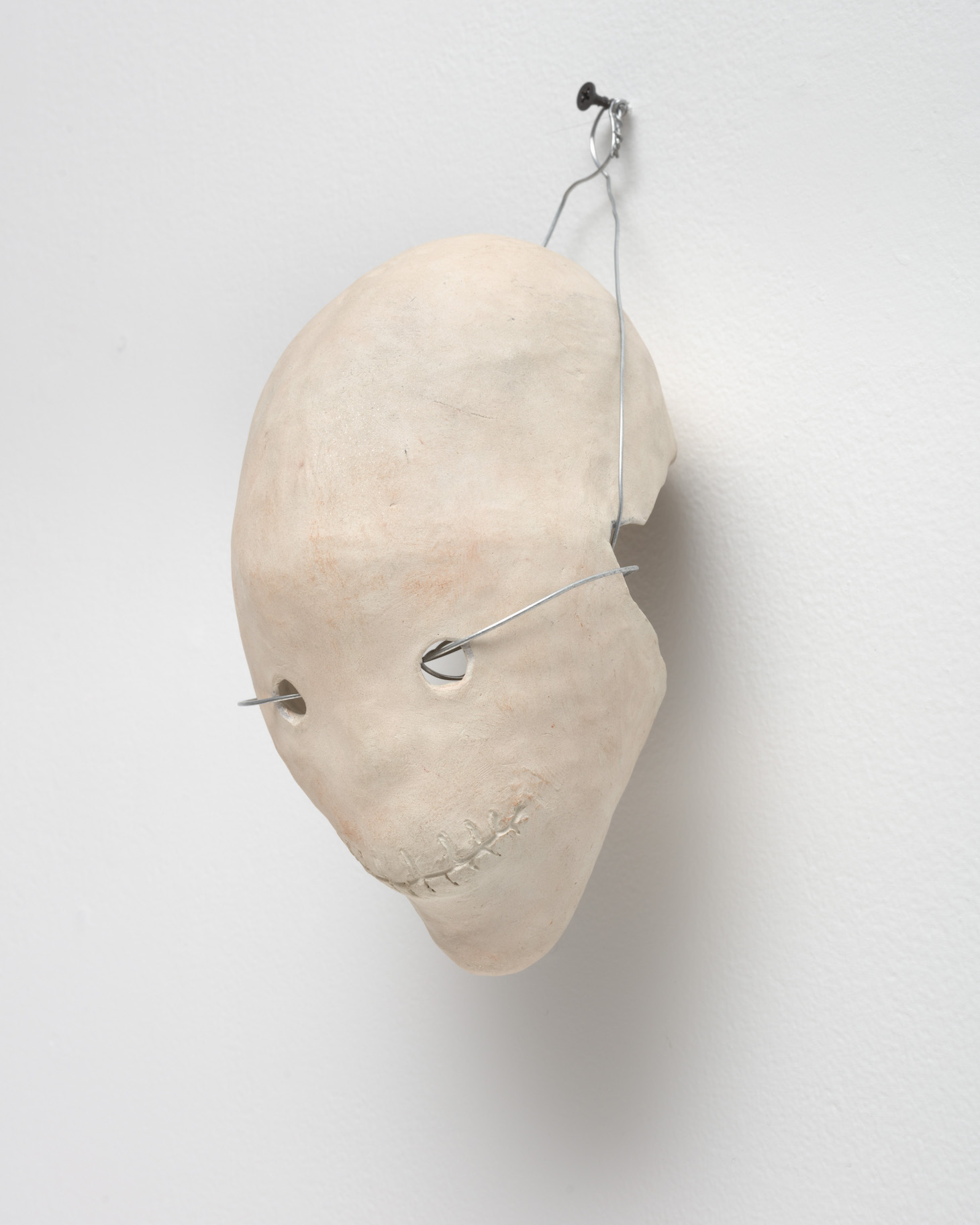

이 전시에서 선보인 초기작 두 점, “십자가 두상Head Crucifixion”과 “철사줄 웨이트레스Wired Waitress” (두 점 모두 1977년 작이다)은 영블러드 작업의 매력이 처음 드러나는 작업으로 그 직접성이 돋보인다.

“십자가 두상”은 표면이 부드럽고 속이 빈, 미색의 타원형 작품이다. 입과 이를 표시하기 위해 긁어만든 봉합선이 보인다. 아니면 사람들이 “슈렁큰 헤드Shrunken Head”를 만들 때 한 것처럼 영혼이 빠져나오지 못하도록 입부분을 꿰맨 표시를 한 것일까? 꿰맨 입의 양쪽 옆으로는 길고 가느다란 막대기가 나와있다. 입에 막대기를 물고 있는 것일까 아니면 눈이 없는 이 얼굴을 뚫고 나온 것일까?

조그만 나뭇가지 두 개가 콧구멍을 나타내며 삐져나와있다. 큰 나뭇가지가 해골의 중앙을 통과해 턱밑으로 뚫고 나와있고, 제목이 말해주는 것처럼, 또 하나의 막대기가 머리의 측면을 뚫고 양쪽으로 나와있다.

눈도 없고 코도 없는 이 얼굴, 다섯 개의 길고 짧은 나뭇가지가 꽂혀 있고 뚫고 있는 이 얼굴을 우리는 어떻게 해석해야 하나? 서로 다른 문화와 전통을 떠올리면서 관련성을 발견하고자하는 관객들이 있겠지만 이 작업은 독창적이면서도 동시에 원형성을 띄고 있어 그러한 분류를 벗어난다. 이 예상 밖의 조합으로인해 영블러드의 작업은 매우 강력하고 매력적이다.

“철사줄 웨이트레스”는 단순하지만 강력하고, 매우 섬세하면서도 퉁명스런 작업이다. 미색의 해골 같은 이 형태에는 입과 이를 나타내는 긁은 선과 눈을 나타내는 두 개의 구멍이 나있고, 벽에 걸려있다. 철사줄이 눈을 통과해서 두개골의 안쪽에서 묶이고 늘여져 턱 뼈가 끝나는 부분을 지나 벽에 박힌 못에 걸려있다.

인간의 죽음과 연약함이 이렇게 섬세하게 표현되는 경우는 드물다. 센티멘탈해지지 않고서 말이다. 그러면서도 오버하지 않는 터프함이 있다. “철사줄 웨이트레스”는 우리가 죽음을 생각할 때 떠올리는 오브제처럼 보이고, 이는 알브레히트 뒤러의 그림 “성 제롬(1521)”의 해골과 유사하다. 성 제롬은 여기서 검지로 해골을 만지고 다른 손은 그의 머리의 한쪽에 대고 있다. “철사줄 웨이트레스”의 표면은 매력적이다. 흙의 물성이 실제 해골보다 더 연약하게 느껴지는데, 희미한 붉은 색 기운 때문에 마치 해골이 얼굴을 붉히고 있는 듯하다.

위에서 나는 영블러드를 구상 조각가라고 했는데, 어쩌면 그녀를 초상 조각가라고, 죽음이라는 주제를 껴안는 초상 조각가라고 하는 편이 더 정확할지 모르겠다.

“칼루 린포쉬(1999)”과 “라마(1996)”는 내면을 들여다보는 듯한 초상들이다. 이 두 작품은 모두 특정적인 개인을 묘사하고 있지만 전혀 이상화시키거나 미화하지 않는다. 그녀 작품의 직접성은 관객은 바로 눈치 챈다. 우리는 그 사람 특유의 성격이 보이지 않는 개인들을 보게 되고, 이는 심난하면서도 끌어당기는 힘이 있다.

달빛이라는 뜻의 “찬드리카(2014)”에서 영블러드는 둥그런 돌 위에 얼굴을 올려놓고 둥그런 돌은 다시 작은 돌로 받쳤다. 얼굴은 비스듬히 기대어져 있는데, 돌의 모양과 닮았고, 코가 있을 곳에 난 구멍으로 다른 색 돌이 보이고, 눈에 난 구멍으로는 큰, 둥그런 돌이 보인다.

영블러드가 말하는 정신세계는 영혼이 더 중요하다고, 육체는 영적 물질로 변형된다면서 물질성을 부인하지 않는다. 돌이 얼굴에 생기를 갖게 한다. 흙으로 빚은 얼굴은 돌의 일부 같으면서도 분리되어 있다. 돌 눈동자에서 볼 수 있듯이 이는 완전히 다른 존재이다.

영블러드가 탁월한 지점이 바로 이것이다. 그녀의 작업에서 드러나는 타자성은 명료하다. 그녀의 작업은 서양 사상사에서, 특히 기독교 사상이나 인본주의와는 거리가 먼 느낌의 사람의 얼굴이나 해골이 놓여있는 공간으로 우리를 데려다 놓는데, 그녀가 뭔가 인용을 하고 있다는 생각이 들지 않는 것이다.

영블러드의 조각은 모두 정교하고 표본 같은 느낌을 주는데, 죽음과 무심한 우주를 향해 난 우리의 피할 수 없는 운명을 증명하려는 듯하다. 그런데도 우리는, 철사줄로 묶이고, 돌이 뾰족한 코가 되는 이 작품들에서 유머와 즐거움의 흔적을 발견하게 된다.

Daisy Youngblood had her first solo exhibition in New York in 1979, when she was in her mid-30s. A figurative sculptor who works primarily with clay fired at low heat, she is not prolific and rarely shows. Daisy Youngblood: Tender Mercy(s): Early and Late Works in Clay at Van Doren Waxter (September 8–October 23, 2021) is her 10th exhibition since the late 1970s and her first with this gallery. It is not to be missed.

The exhibition includes seven works: six in one room of the gallery and the other, a large, smooth, deep black “Gorilla” (1996) made of bronze, seated on a pedestal in the lobby. A lot of artists make sculptures of animals, but the two who seem to me to fully recognize the otherness of their subject are Youngblood and Deborah Butterfield. This is something they achieve through their merging of subject and materials. Their animals are entities that are completely separate from us, no matter what our interaction may be.

This otherness is what comes through in the ashy gray sculpture “Little Gorilla” (2020), which is a shade over 12 inches high. Admittedly, I am using anthropomorphizing terms when I describe “Little Gorilla” as proud, stern, self-contained, fierce, strong, magisterial. At the same time — and this is part of what sets apart Youngblood’s work — the expression is also unreadable. At some point, while describing the feelings radiating from this shaped lump of fired clay, you may come up against the limitation of words and think you might begin by describing what the sculpture is not — warm or friendly — or you may focus on the ashy gray materiality of the piece and all that it stirs up in you.

The exhibition’s two earliest works, “Head Crucifixion” and “Wired Waitress” (both dated 1977), show the first signs of what makes Youngblood’s work so compelling, beginning with its immediacy.

“Head Crucifixion” is a smooth, hollow, off-white ovoid with an incised line to mark the lips meeting and teeth — or is it a mouth sewn shut, as is done with shrunken heads so that the soul cannot escape and haunt us? Piercing the head on either side of the incised lips and teeth is a long, thin stick. Is the mouth holding the stick or has it pierced through the eyeless face?

Two twigs stick out indicating the nostrils. A larger stick pierces the top of the skull and reappears below the chin, while another sharpened stick penetrates the side of the head until it extends out of the other side, hence the work’s title.

What are we to make of this eyeless, featureless head pierced by five sticks of varying lengths and thicknesses? While the viewer might associate aspects of the work with different cultures and traditions, it escapes these categories to become both original and archetypal. This unlikely synthesis is what makes Youngblood such a powerful and engaging sculptor.

“Wired Waitress” is a simple, haunting work, at once delicate and blunt. An off-white skull-like form with incised lines indicating lips and teeth, and two holes for eye, hangs down from the wall. A metal wire has been inserted through the eyes, and knotted in the skull’s interior, and then extended out from where the jawbone normally ends and looped around a screw inserted into the wall.

Mortality and vulnerability have rarely been so tenderly expressed without devolving into the sentimental. If anything, there is a no-nonsense toughness to the piece. “Wired Waitress” seems to be an object we might contemplates while thinking about our mortality; it is kin to the skull in Albrecht Dürer’s painting “St. Jerome” (1521), which the saint touches with his forefinger, his other hand pressed to the side of his head. The surface of “Wired Waitress” is inviting. The materiality of the clay feels more vulnerable than an actual skull, while the faint touches of red make it appear as if it is blushing.

Earlier, I described Youngblood as a figurative sculptor, but perhaps it is more accurate to say that she is a portrait sculptor whose themes include the embracing of one’s mortality.

“Kalu Rinpoche” (1999) and “Lama” (1996) are portraits whose subjects appear to be looking inward. Both seem specific to an individual and not in any way idealized or improved; it is that directness in Youngblood’s work that I think viewers sense immediately. We see individuals without traces of a personality, which is unsettling and magnetic.

In “Chandrika” (2014), translated as “moonlight,” Youngblood rests a face on a rounded stone, balanced against a smaller stone. The face, which tilts upward, conforms to part of the stone’s shape, and a different-colored stone emerges from a hole where the nose would be, while the main stone is visible through the eyeholes.

Youngblood’s notion of the spiritual does not reject materiality in favor of a soul and the transformation of the body into holy matter. The stone animates the face. The clay face is part of the stone and separate from it. It is also completely other, as the stone pupils convey.

This is Youngblood’s genius. The otherness evoked in her work is unmistakable. She transports viewers to a space occupied by a human face or skull that is not marked by Western thought, particularly Christianity and humanism. And yet, I don’t feel that anything she does is citation.

There is something precise and specimen-like about each of Youngblood’s sculptures, evidence taken from our unavoidable journey toward death and the indifferent universe. And one can see in all these works — in the tying of the wire or the stone that becomes a pointy nose — traces of humor and joy.

Daisy Youngblood: Tender Mercy(s): Early and Late Works in Clay continues at Van Doren Waxter (23 East 73rd Street, Manhattan) through October 23.

RELATED POSTS