한국의 미학과 막의 정체성

Korean Aesthetics and the Identity of Mahk

01

Text by 조병수 Byoungsoo Cho

Translation by 박상미 Mimi Park

나는 항상 한국 건축의 정의, 핵심, 혹은 특징이 무엇인지 만족스럽게 설명하는 것에 대해 고민해왔다. 이는 한국 건축이 명확한 문화적 특징이나 예술적 어휘가 없어서가 아니라, 언어적 표현으로 온전히 담아내기엔 어려운 요소들이 많이 있었기 때문이라 생각한다.

한국의 미적 특성은 수천 년 동안 혹독하고 변화무쌍한 자연과 사회정치적인 상황 속에서 생존하기 위한 한계 상황들로 인해 다듬어져 왔다. 물론 이것은 세계의 어떤 문화에서도 동일하며 한국의 미학이 다른 동아시아권의 미적 어휘와 연관되어 있다는 것 또한 사실이나, 한국의 미는 단연 그 자체만의 독특한 정서를 보여주며 이는 한번 인식하게 되면 결코 놓칠 수 없는 독창적이고 고유한 아름다움이다.

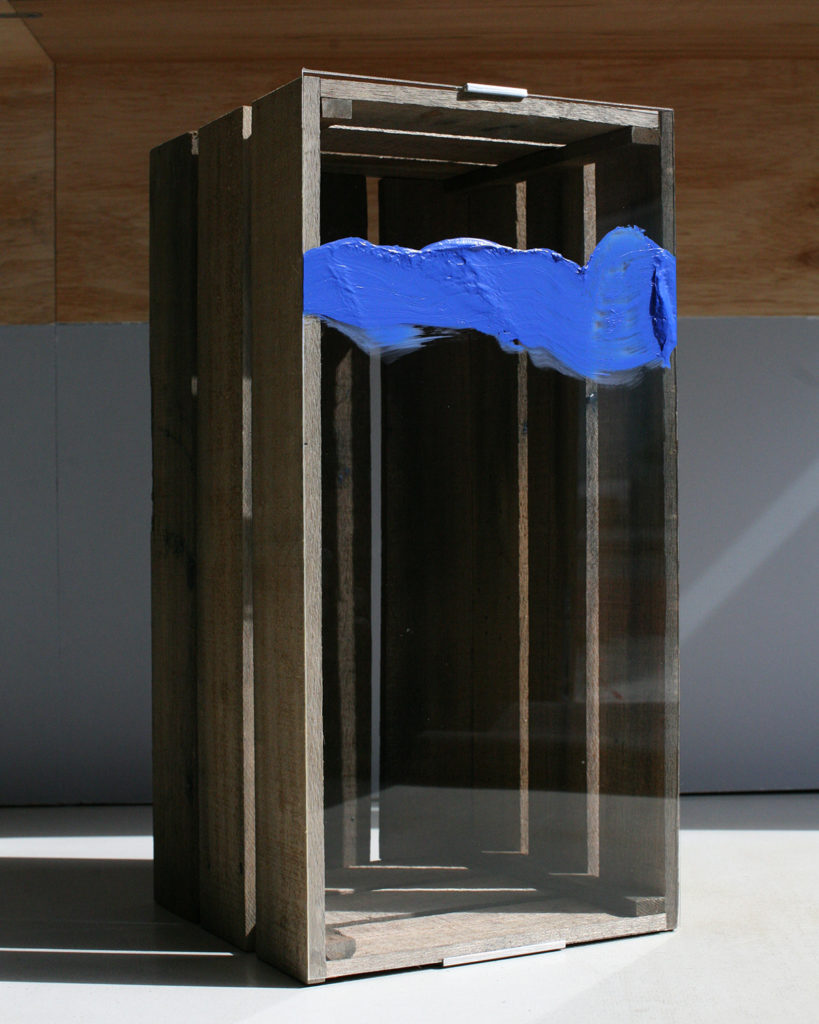

한국의 미적 특성은 감각적으로 혹은 즉흥적으로 덜 채워진 채로 완성되는 ‘막’ 정신에 의해 설명될 수 있겠다. 이러한 정신은 전통음식, 음악, 글, 춤 그리고 다른 모든 한국의 예술에 깃들어 있다.

‘막’이라 함은 한국어에서 높은 완성도를 의미하는 용어는 아니다. 예전부터 서민들의 문화 속에 자리잡혀 있는 쌀 발효주인 막걸리에서 볼 수 있듯이 청주를 떠내지 않고 그대로 걸러내어 정제되지 않음을 나타낸다. 심지어 어떤 문구에서는 공들이지 않음을 내포하기도 한다. 하지만 내가 말하고자 하는 ‘막’의 핵심개념은 실질적으로 과도하게 공들이지 않은, 즉 겉치레를 뺀다는 데에 있다. “막”은 과시와 정제를 위한 모든 과정을 과감히 거부하고 꾸미지 않은 정직함과 실용성에 도달하는 과정에서 얻어진다. 한국의 전통건축을 들여다보면 ‘막’은 배치계획, 디자인, 재료선정, 시공에 이르기까지 건축 과정의 전반에 영향을 미쳤다는 것을 알 수 있다.

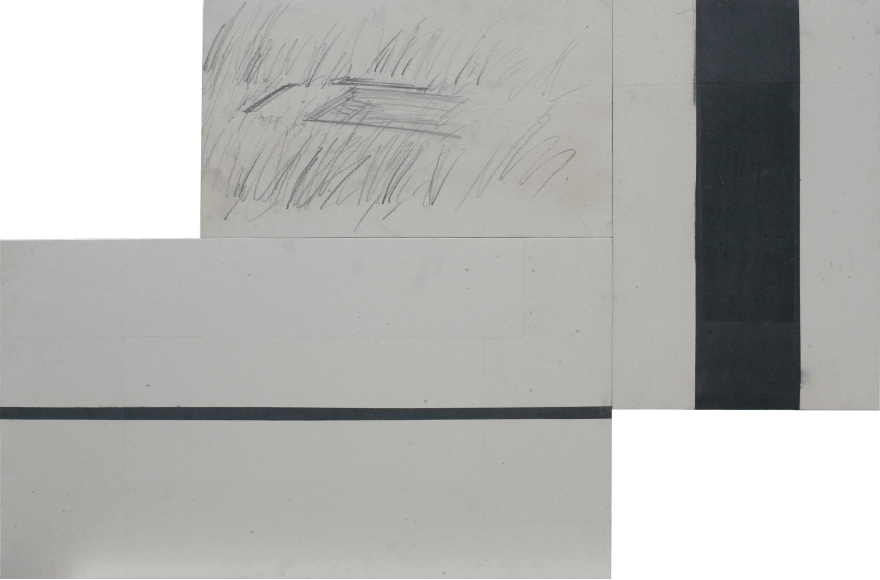

‘막’은 한국적 ‘空’의 개념인 비움과 궤를 같이한다. 비움은 단어 그대로 물리적인 의미뿐만 아니라 비유적인 의미 또한 내포하고 있다. 그 예로 한국의 장인정신과 미학의 모범인 한옥의 고아한 품위에서 찾을 수 있다. 다른 문화에서의 오차 없는 나무 짜임과 정확한 각도의 맞춤, 그리고 양면 대칭과는 대조적으로 한옥은 뒤틀린 나무의 형태, 다듬어지지 않은 표면, 재료와 지형의 자연스런 기울어짐을 허용한다.

한옥은 엄격한 전통과 과장된 이상보다는 공간과 재료의 효율적인 사용을 중시하였고 겉치레와 연출된 모습에 대해 관심을 두지 않았다. 그리고 모든 한옥의 중심에는 마당이 있다. 한옥은 하나 이상의 직사각형 모양의 안뜰이나 중정인 마당을 중심으로 이루어진다.

깔끔히 정돈되고 의도적으로 비워진 마당은 한옥의 모든 방으로 그 빛을 반사하고 거주자들이 서로 그들의 거처, 혹은 자연과 상호작용할 수 있는 공간을 제공한다. 한옥의 모든 각도와 위치는 땅의 풍수지리에 기초한 공간 구성에서부터 계절과 시간에 따라 한옥의 모든 부분으로 퍼지는 빛까지 꼼꼼하게 계획되었다. 외향적으로는 다소 소박히 보일지 모르나, 고도로 실용적이고 꾸밈없으며 채워지지 않는 비움으로 가득 찬 공간으로 이루어져 있다. 이러한 여유의 공간 미학은 용도에 따라 즉흥적으로 완성하는 ‘막’의 미학 정신과도 통해있다.

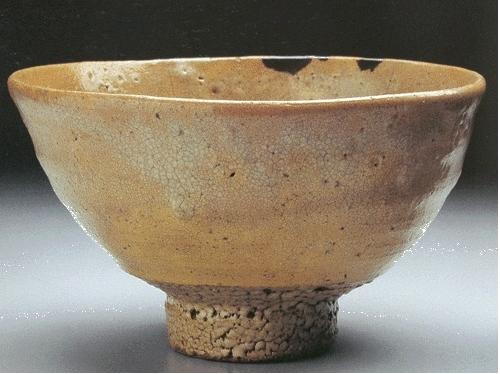

역사적 관점에서 ‘막’과 ‘비움’은 고려 시대와 조선 시대 선비의 자연주의적 세계관을 반영한다. 한국의 선조들은 도예, 글, 춤 등의 창작 작업에 심취하면 예술가의 사고 안에서 더 큰 창조적인 힘이 그 행위를 주도하게 된다고 믿었다. 한국의 소박한 도자기인 ‘막사발’(여기서도 ‘막’의 접두어가 사용된다.)을 전형적인 예로 들 수 있다. 막사발은 흔하고 거친 재료로 유용성을 염두에 두고 만들어졌으며, 물 흐르듯 막힘없이 이루어진 작업으로 얼핏 보면 잘못 만들어진 것처럼 보일 수 있다. 분청사기 같은 다른 조선 시대 도자기 예술품들도 역시 당당히 그 본질적 특성을 고스란히 보여준다. 그들의 거친 손자국 표면은 원료인 값싼 진흙의 거침을 그대로 드러낸다.

‘막’은 의식의 흐름을 따라갈 때 그 속에서 찾아지는 형태의 진정성을 가장 잘 보여준다. 이 독특한 도자기의 형태는 ‘물아일체(物我一體)’의 결과이며 본질적인 단순함으로 인해 숭고함의 경지에 이른다고 말할 수 있다.

과장과 꾸밈을 배제하는 것은 비움을 나타내는 일환이다. 형식적인 경직성을 깨고 실용적 편안함으로 욕심을 비우는 정신이 바로 ‘막’이다. ‘막’을 창조하는 데 있어 장인의 비움에 가까운 무념의 상태가 또 다른 비움의 한 형태로 간주될 수 있다. 따라서 ‘막’과 ‘비움’은 서로 연결되어 있으며 동시에 서로 촉매 역할을 한다. 이 둘은 창조의 내재적 즐거움을 주며 완성된 작품을 통해 빛을 발할 수 있게 해준다. “막”과 “비움”은 이렇게 위대한 예술에 도달할 수 있는 막연하면서도 고상한 품위를 지니고 있다.

한국의 전통건축물은 주변의 자연환경을 그 우위에 두어 땅 정상의 위치를 차지하기보다는 그 아래 흐르는 계곡을 따라 조용히 위치하며 바람을 피하고 혹독한 계절의 반도적 특성에 의한 지형 기후에 맞게 그 모습을 갖추어 왔다. 일례로 한국의 유명한 전통사찰 부석사를 방문한다면 동시대의 중국과 일본 사찰에서 보여지는 대칭적 혹은 평면적 배치 방식과는 다르게 자연의 굴곡과 흐름을 따라 유기적으로 배치되어 자연과 융합되어 있는 것을 발견할 수 있을 것이다. 입구에서 사당까지 비스듬히 놓여있는 건물들 사이에는 빈 공간이 간격을 채우고 있으며, 이렇게 부석사의 건물들은 마치 기존 지형으로 스며드는 것 같으며 산에 위치하는 건물의 특수성 안에서 완성된다.

16세기 향교인 병산서원에서는 협곡 위에 건물의 육중한 무게를 지탱하고 있는 굽은 기둥들을 발견할 수 있다. 이는 긴 세월에 의해 불완전한 형태로 휘어진 것이 아니라 원래 이런 형태로 만들어진 것이다. 이 불규칙적인 기둥들은 자연에서 온 재료 그 자체에 대한 순응과 경의를 나타내는 상징이다. 이 비대칭성은 물아일체의 상태에 있는 도예가의 모습을 떠올리게 하고 깔끔히 손질되지 않은 날 것의 상태는 자연의 무질서 속에 내재된 신성한 완전함에 경의를 표하고 있다. (계속)

Korea’s aesthetic character has been hewn over millennia (Koreans widely regard the nation as being about 5000 years old), wrought by the limitations of surviving within an often-harsh, always-evolving, amalgam of natural forces and socio-political factors. Of course, this can be said of any culture in the world, and it’s also true that the visual language of Korea has ties with those of others in East Asia– yet it displays idiosyncrasies that are singularly emotive, and impossible not to notice once one has been made aware of them.

The Korean worldview is underlined by a deliberate making of space to improvise; space for spontaneity, the spirit of which I will refer to with the Korean adjective, mahk. This spirit permeates the original food, music, writing, dance, and other arts in Korea. But “mahk” is not an elevated term in Korean vernacular. It can infer crudeness, appearing in the beginning of words such as mahkgulli, an unfiltered rice wine long associated with old school working-class culture. Though in some contexts, it can even go so far as to imply carelessness, at its core, mahk is simply a lack of embellishment, a matter-of-fact departure from the overwrought in general. Mahk is an unapologetic rejection of refinement for the sake of refinement, of ostentation that gets in the way of practicality or honesty. In the indigenous architecture of Korea, mahk begins its influence in the initial site planning stages, and resurfaces again and again, indeed, is the driving force behind, the processes of design, material selection, and construction.

Mahk goes hand in hand with bium, the Korean notion of emptiness–emptiness in a literal and physical as well as in a more figurative one. Take for example hahnoke, traditional houses. They’re exemplary of Korean craftmanship and aesthetics, with humbly dignified defining characteristics that can be found from the lowliest dwellings to the hahnoke of the elite ruling classes of antiquity. Where other cultures may prefer precisely sawed wooden details, right angles at every turn, and bilateral symmetry throughout, hahnoke revel in warped wooden contours, unfinished surfaces, and a certain permissiveness towards the natural inclinations of the site and materials.

Rather than strict traditions and overarching ideals, traditional Korean architecture is above all, guided by the hyper-efficient usage of space and material and a disinterest in pretension or even feigned authenticity. And, at the center of it all: mahdahng. Traditional Korean architecture is reliably anchored by one or more rectangular courtyards, or mahdahng. Traditionally clean-swept and kept deliberately bare, mahdang reflect light into the rooms of the hahnoke, and provide a private space for the residents of a hahnoke to interact with one another, their home, and with nature. Though every angle and positioning of the hahnoke was planned down to meticulous detail, accommodating everything from spiritual beliefs about the energy flow on a given parcel of land, to the way the sunlight would reflect from the clean-swept ground into various parts of the hahnoke at every time of day and year, in the end, they were rather humble in appearance– again, hyper-practical, unadorned, and full of emptiness.

In historical context, mahk and bium reflect on a naturalistic understanding of the world akin to the ideals of the Confucian sunbi (‘virtuous scholars’ who “[passed] up positions of wealth and power to lead lives of study and integrity”) of the Goryuh (918-1392) and Josun (1392-1897) periods; ideologies that are imbued with an affection and respect for the connection between universal pathos and the act of creating.

Further, like the ancient Greeks and their muses, Koreans of antiquity believed that during periods of intense creative work, whether in pottery, writing, painting, dance, and so on, the artist’s own thought gave way to intuitive channeling of a greater creative force. This is epitomized in mahksahbahl (notice again the “mahk” prefix), unadorned Korean ceramicware. Mahksahbahl were created with utility in mind, from humble, unrefined materials, and in such haste that the speed of the work is clearly visible in somewhat mishappen appearance of the pieces. Other ceramic artifacts of the Josun Dynasty, such as boonchung, also display this unabashedly visceral nature. Their rippled surfaces emerge from the coarseness of the cheap clay that they were made from. Mahk is the ultimate epitome of the inevitable authenticity of form following function. The distinctive ceramic forms that arose as a result of a single-minded regard for function, ultimately came to be revered for their profoundly simple form, which some say verges on the sublime.

I think of the lack of adornments and fuss can be thought of as one manifestation of bium; the unbothered spirit of disregarding formal rigidity is an example of mahk. The empty-vessel state of the artisan when creating mahk can also be regarded as another form of bium. Bium and mahk are thus intertwined, catalyzing one another. They allow an innate joyousness in the act of creation to shine through the finished work. There is no room for the grandiose where there is mahk and bium, but mahk and bium hold space for some evasive, higher other quality that more grandiose art perhaps reaches for.

In my opinion, truly Korean architecture abdicates to its natural surroundings, relinquishing the hilltop to instead stretch quietly across the rolling valleys below. In a peninsula defined by its rocky, steep mountains and harsh seasons, topographical and climatic challenges have determined the character of the indigenous architecture. To exemplify this, we might visit the Busuhksa Temple, perhaps the most famous of the traditional religious sites in Korea. Though prominent examples of Chinese and Japanese Buddhist temples from the same period follow clear axial arrangements regardless of terrain, the architecture at Busuhksa melds with nature with elegant pragmatism. Buildings skew from entrance to shrine, paced by large, pregnant voids between them; the arrangement of the compound seemingly melts into the mountains, and one cannot experience being in the structures without simultaneously experiencing being in the mountains.

At Byungsahnsuhwun, a sixteenth century Confucian school, you will find withered columns lifting the weight of the building’s mass above a ravine. Their apparent imperfections are not a concession to aging. They were built this way. The wavering irregularities of the Byungsahnsuhwun columns radiate with a deference to the natural materials themselves. Their asymmetry brings to mind the intuitively unthinking hands of a potter in a meditative flow-like state of working, and their unmanicured state pay tribute to the sacred perfection inherent in the messiness of nature.

*

Works Cited

A. B. Cook (1914), Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, Vol. I, p. 104, Cambridge University Press.

Cartwright, Mark. “Korean Pottery.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia, 25 Oct 2016. Web. 16 Jan 2020.

Choi, Wan Gee (2006). The Traditional Education of Korea. Ewha Womans University Press. pp. 29–30. ISBN 9788973006755. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

“Chosŏn dynasty: Korean history”. Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

Kwon, Heonik “Healing the Wounds of War: New Ancestral Shrines in Korea,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 24-4-09, June 15, 2009.

Leaman, Oliver (Oct 19, 2006). Encyclopedia of Asian Philosophy. Routledge. p. 143. ISBN 9781134691142. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

Szczepanski, Kallie. “The Ceramic Wars: Hideyoshi’s Japan Kidnaps Korean Artisans.” ThoughtCo, Jul. 3, 2019, thoughtco.com/ceramic-wars-hideyoshis-japan-kidnaps-koreans-195725.

RELATED POSTS