낡고 오래된 책장의 기억: 라우셴버그의 북아프리카 콜라쥬

Magical Keepsakes: North African Collages by Rauschenberg

01

Text by 존 야우 John Yau

Translation by 박상미 Mimi Park

I.

1952년 가을, 로버트 라우셴버그가 사이 톰블리와 함께 유럽으로 여행을 떠날 무렵, 라우셴버그는 이미 광범한 미디엄과 재료로 유의미한 작업을 한 상태였다. 그는 1949년 사진을 찍기 시작했는데, 그 중 상당 부분을 에드워드 스타이첸이 모마의 컬렉션으로 구입했고, 이는 최초로 미술관에 소장된 그의 작업이다. 1949-1950년에는 수잔 웨일과 공동으로 청사진을 빛에 노출 시키는 방법의 모노프린트 연작을 제작했다. 1950년에는 <두 개의 영혼을 가진 남자>라는 제목의 성적인 뉘앙스가 담긴 아상블라쥬를 제작했고, 1951년 여름에는 <밤의 개화>라는 제목의 검은색 회화 연작을 했다. 그 해 가을에는 <흰색 회화>를 완성했고, 새로운 검은 회화 연작을 시작했다.

![robert-rauschenberg-untitled-christian-symbol-ca-1952-sonnabend-collection-foundation-and-antonio-homem Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled [Christian symbol], 1952](https://clumsy.site/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/robert-rauschenberg-untitled-christian-symbol-ca-1952-sonnabend-collection-foundation-and-antonio-homem.jpeg)

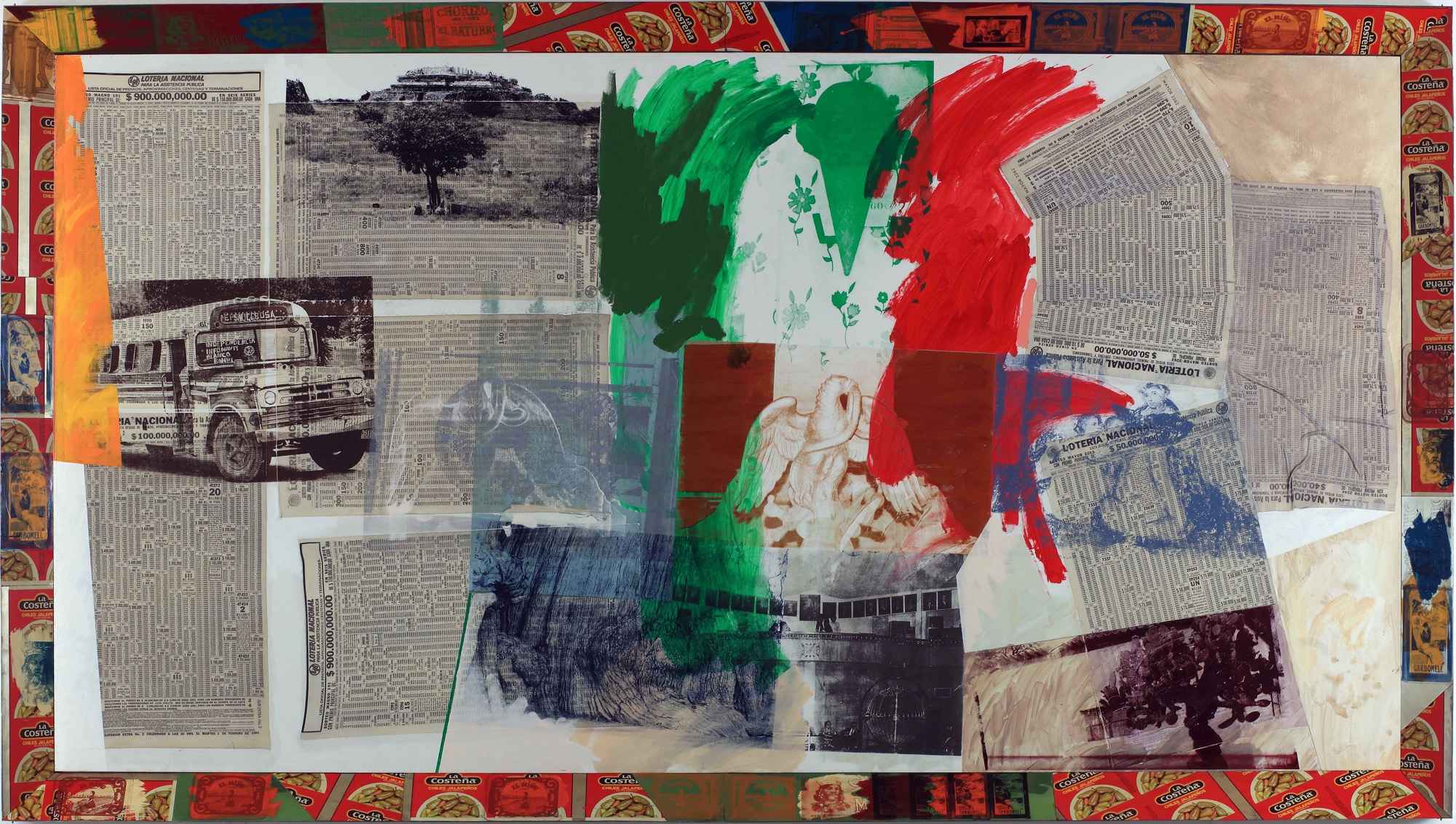

라우셴버그는 왕성하게 작업하는 것으로 알려졌지만 그렇다고 해서 무차별적인 것은 아니었다. 이 사실을 기억하는 것은 중요하다. 그는 당시 20대 중반이었지만, 급진적으로 다양한 방법과 재료로 실험적인 작업을 하는 개방적인 작업 태도에 관해선 이미 따라올 사람이 없었다. 그의 오랜 경력 동안 작업 반경은 점점 커졌고, 결국엔 “라우셴버그 해외 문화 교류(ROCI)” 프로젝트라는 거대한 작업까지 탄생하게 되었다. 바로 이런 이유 때문에 그가 1952-53년 해외 여행 당시 제작한, 이 친밀한 스케일의 콜라쥬가 더욱 흥미롭게 느껴진다. 사이즈는 작지만 이 콜라주들은 라우셴버그의 작업 방식에 있어 큰 전환점이 된, 또 그의 더 유명한 작업들의 탄생을 예고하는 선구적인 작업이었다고 할 수 있다.

II.

1952년 가을과 1953년 봄 사이에, 라우셴버그는 톰블리와 함께 로마에 머무르고, 북아프리카를 여행하면서 3편의 독립적인 작업을 완성했는데, 의도적으로 프레임하지 않은 작은 크기의 콜라주들, 작은 상자 안에 든 앗상블라쥬, 그리고 벽에 거는 “페티쉬” 앗상블라쥬들이 그것이다. 이외에도 그는 그 시기에 수많은 사진들과 유명한 연속 사진인, <사이 + 로마의 계단 (I, II, III, IV, V)>을 완성했다.

믿을 수 없을 정도로 다양한 라우셴버그의 작업들을 보아도 알 수 있지만, 이 콜라쥬들과 상자 앗상블라쥬를 통해 그는 손에 쥐는 것마다 예술로 전환시키는 탁월한 능력의 소유자라는 것을 다시 한 번 확인하게 된다. 여기서 드러나는 멈추지 않는 상상력과 기술로 그는 뭐든 쉽게 할 수 있다는 인상을 받게 되는 것이다. 이들은 또한 나중에 나오게 되는 그의 컴바인과 실크 스크린 회화 작업을 예고하는데, 직사각형 안을 채운 다양한 재료와 이미지의 조합은 앞으로 나올 그의 작업의 중요한 모델이 된다.

III.

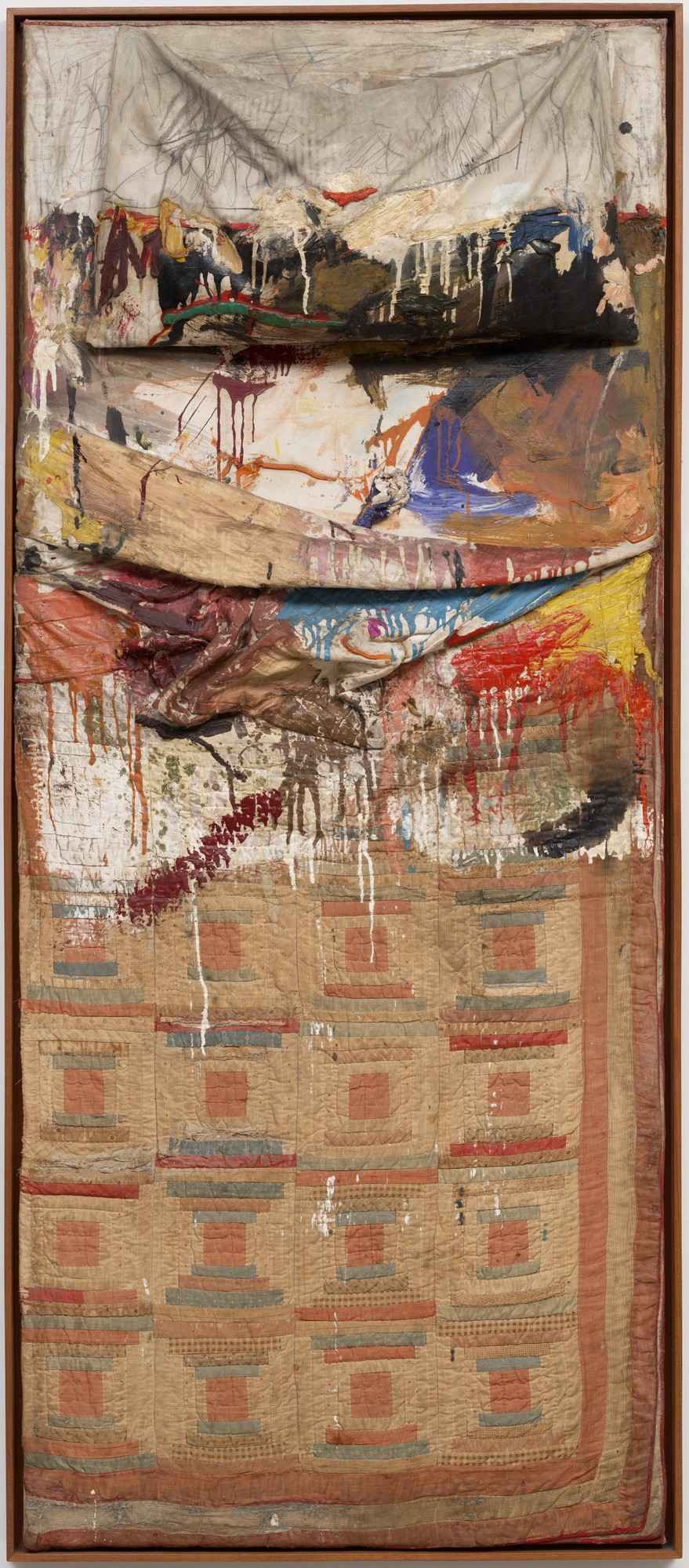

우리의 예상과는 달리, 라우셴버그의 콜라쥬는 바탕 위에 뭔가를 붙이는 전통적인 두 겹의 방식이 아닌, 주로 세 겹으로 이루어진다. 바탕에는 두 겹이 깔린다. 즉, 다림질한 셔츠가 구겨지는 것을 방지하기 위해 사용하는 보라빛 회색의 마분지를 깔고, 그 위에 누런 빛깔의 종이를 붙인다. 이렇게 중립적인 느낌의 바탕이 마련되면, 라우셴버그는 그 위에 오래된 판화를 오린 종이나, 아라비아 글씨가 프린트된 종이, 티슈 페이퍼 등을 붙여 작업을 완성했다.

![스크린샷 2021-10-28 오후 6.34.15 Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled [black painting with portal form], 1952–53](https://clumsy.site/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/스크린샷-2021-10-28-오후-6.34.15.png)

라우셴버그가 사용한 재료는 주로 북아프리카 여행 중 책 가판대나 벼룩시장 등에서 수집한 출판물에서 왔다. 그는 또한 누런 빛깔의 종이 위에 연필, 잉크, 구아쉬 등을 사용했다. 그가 이 콜라쥬들에 넣은 모든 것들은 전체적인 구성, 즉 색과 형태, 비례에 맞도록 사용되었다. 접착제도 접착제로서의 기능 뿐 아니라 얼룩이나 흔적을 남기도록 의도된 것이다.

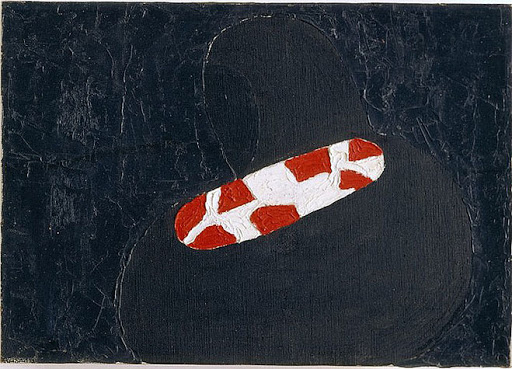

<흰색 회화>와 <검은색 회화> 다음에 나온 이 콜라쥬들은 라우셴버그가 색채 작가라는 것을 확인시켜주는데, 그는 톤을 변화시키고 강렬한 대조를 주는데 주로 관심이 있었다. 그가 재료 선택이나 배열, 색 사용해서 있어 얼마나 섬세하게 작업했는지를 보면 그가 과격하기만 한 작가라는 시각이 잘못된 것임을 알 수 있다. 그는 파격적으로 보이지만 이 작업들을 통해서 작은 하나의 선택도 우연히 일어난 게 아니라는 것을 알 수 있다. 내재적인 논리와 예상치못한 연계가 작업 도중 일어나고, 이 콜라쥬들은 다른 방식이 아닌, 이런 방식으로 만들어져야 했다는 필연적인 느낌마저 준다.

![52.D006_00 Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled [pictographs and feathers], 1952](https://clumsy.site/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/52.D006_00.jpg)

IV.

대개 바탕 마분지는 두 가지 포맷으로 제작되었다. 수직으로 기다란 직사각형(14 x 5 인치) 그리고 거의 정사각형에 가까운 크기(10 x 7 인치)가 그것이다. 수직으로 길고 좁은 포맷에는 직사각형 윗쪽 끝에 작은 미색 종이를 붙였는데, 언제나 그 주변 여백을 민감하게 분배해서 남긴 것을 볼 수 있다.

이 작업들은 각각 최소한 3개의 요소가 작용하는데, 바탕의 형태와 색, 그 위에 붙인 미색 종이의 형태와 색, 그리고 그 위에 붙인 콜라쥬의 내용, 즉 이미지 또는 도표, 또는 어떤 종류의 글씨다. 그는 여기에 종종 예상하지 못한 어떤 요소, 즉 기다란 천조각이나 연필선, 접착제 자국을 더하기도 한다.

사각형 안에 사각형 안에 사각형. 한 형태 안에 같은 형태를 놓는 방식, 그 형태가 주변 공간의 색과 상호하는 방식을 보면 마크 로스코의 그림이 떠오른다. 모든 요소가 다 눈에 보이긴 하지만, 이는 무언가의 내부에 또 무언가가 있고, 다시 그 내부에 뭔가 존재하는 것에 관한 것이다.

라우셴버그가 좁은 공간 안에 콜라쥬 요소를 얹은 것을 보면 그가 위에서부터 아래로 작업하는 것을 볼 수 있다. 그가 작은 요소들을 미색 종이 위에 얹을 때 그는 언제나 그 아래 공간과의 관계를 고려한다. 콜라쥬 작품 전체적으로 대칭과 비대칭 사이의 긴장이 존재하고, 그것이 이 작업의 시각적인 강점이다.

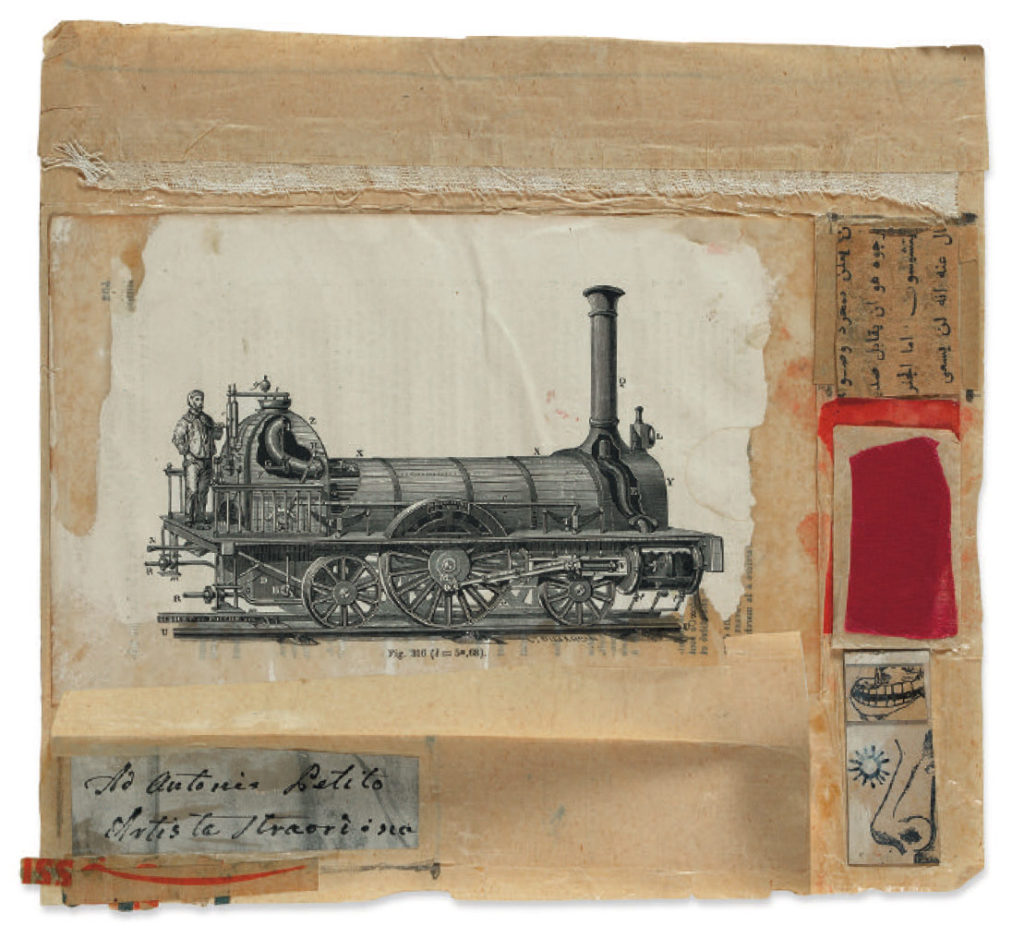

정사각형에 가까운 포맷에서도 라우셴버그는 위에서부터 아래로 작업하는 듯하고, 콜라쥬 요소를 가장자리까지 펼쳐서 매우 좁은 여백만을 남긴다. 어떤 경우에는, <무제(기관차)>에서처럼 중앙에 놓인 이미지를 둘러싸고 인쇄물이나 색이 칠해진 콜라쥬 요소가 놓인다.

시각적으로 콜라주는 단순한 추상에서 이미지와 아랍 문자가 가득한 꽉 찬 구성까지 다양하다. 이들은 서사적이지 않지만 어떤 심상을 불러일으킨다.

V.

라우셴버그는 이 콜라주들에 액자를 하지 않았는데, 그 이유는 관객들이 잃어버리거나 잊혀진 책들에서 온 책의 한 페이지를 보듯, 이들을 손에 들고 볼 수 있게 하기 위해서였다. 그는 예술과 삶이 분리되는 경계를 없애고, 사람들이 이 작업들과 직접 상호작용하는 것을 원했다.

<무제(상형문자와 깃털)>에는 중앙에서 접합된 두 겹의 종이 레이어가 있고, 이는 펼쳐볼 수 있는데 그 안쪽에 하나는 빨강, 하나는 청록색의 밝은 색의 깃털들이 있다. <무제(기독교 상징)>에는 위쪽에 크리스토그램(그리스어로 그리스도의 첫번째 두 글자로 구성된) 아래 주머니가 있고, 그 속에 접혀진 종이가 꽂혀있다.

이 인터액티브 콜라쥬들은 라우셴버그의 다른 작품, 작은 상자 앗상블라쥬 <무제 (스카톨리 퍼스날리)> 와 통하는 데가 있다. 이 작품은 루카스 사마라스의 상자 작업들을 예고하는데, 죽음에 관한 암시로 가득차 있어서, 은밀하고 위협적이고 잊혀지지 않는 종류이다. 이를 열어보면, 우리는 또 다른 종류의 상자를 보게 되는데, 작가의 사진 조각이 렌즈 아래 놓여있고, 렌즈는 먼지로 부옇다. 사진 양쪽으로 각각 두 줄의 핀이 수직으로 꽂혀있어 마치 조용하지만 사나운 파수꾼처럼 사진을 보호하고 있는 듯하다. 라우셴버그는 일상적인 사물을 이용해 자신의 조각난 일부가 들어있는 성유물함 같은 것을 만들어 그가 가는 곳마다 갖고 다닐 수 있게 했다. 이는 우리가 얼마나 멀리 떠나 여행을 가든 우리를 따라오는 것이 있다는 것을 암시하고 있는 듯하다.

I.

By the fall of 1952, when Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly sailed to Europe, Rauschenberg had already completed substantial bodies of work in widely different mediums and materials. In 1949, he started taking photographs, a number of which were acquired in 1952 by Edward Steichen for the Museum of Modern Art, New York, making them the first of his works to enter a museum collection. In 1949–1950, he collaborated with Susan Weil on a series of monoprints, made by exposing blueprint paper to light. In 1950 came the sexually charged assemblage The Man with Two Souls. In the summer of 1951, he finished Night Blooming, a series of black paintings. In the summer and fall of 1951, he completed the original set of White Paintings, and began a variety of new black paintings.

![스크린샷 2021-10-28 오후 9.50.54 Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled [locomotive], 1952](https://clumsy.site/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/스크린샷-2021-10-28-오후-9.50.54.png)

Rauschenberg was voracious but not—and this is important to remember— indiscriminate. Although he was only in his mid-twenties, it was already apparent that he was largely unrivaled in his openness to experimenting with radically different methods and materials in his work. History tells us that he only became more so over the course of his long career, as his work grew ever larger, finally to the epic proportions of his Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange (ROCI) projects.This is one of the reasons I find the intimately scaled collages he made in 1952–53, while living abroad, so interesting. Despite their modest size, they represent an important turning point in Rauschenberg’s approach to art and also anticipate many well-known works.

II.

Between the fall of 1952 and the spring of 1953, while staying in Rome and traveling through North Africa with Twombly, Rauschenberg completed three self-contained bodies of work—deliberately unframed, modestly scaled collages, small boxed assemblages, and hanging “fetishistic” assemblages—along with numerous photographs, including his well-known sequence, Cy + Roman Steps (I, II, III, IV,V), 1952.

![스크린샷 2021-10-28 오후 10.01.21 Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled [insects], 1952](https://clumsy.site/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/스크린샷-2021-10-28-오후-10.01.21-1.png)

Knowing what we do about Rauschenberg’s unbelievably diverse career, these collages and boxed assemblages are revelatory in the way they demonstrate his unique ability to turn whatever is at hand into art. Although we know otherwise, his unstoppable imagination and dexterity conveyed the impression that he could do everything almost without effort. Equally important is their prefiguring of later bodies of work, particularly the combines and the silkscreen paintings. In their arrangement of diverse materials and images within a rectilinear composition, one sees a model of things to come.

III.

In contrast to what we might expect, Rauschenberg’s collages are often made of three layers rather than the two that are found in a conventional figure-ground duality. The bottom consists of two layers: first a stiff mauve-gray paperboard that was commonly used to prevent wrinkling in laundered shirts; over that he affixed a piece of buff-colored paper, which became a neutral zone where Rauschenberg would glue a cut-out section of an old engraving, paper printed with Arabic script, and tissue paper.

Rauschenberg’s sources were bookstalls and flea markets, along with the printed material—and other stuff—he collected during his travels in North Africa. He also used pencil, ink, and gouache on the buff-colored paper. Everything that Rauschenberg put into his collages is integral to the composition, including the support’s color, shape, and proportions. In addition to being an adhesive, glue was also used to make a stain or mark.

Coming after his White Paintings and black paintings, the collages prove that Rauschenberg was a colorist, primarily interested in shifting tonalities and sharp contrasts. Certainly his sensitivity to materials, placement, and color belies the view that he was indiscriminate in his approach. In fact, for all of his seeming wildness, his choices never come across as arbitrary in these works.There is an internal logic, unexpected links discovered in the making.There is an aura of inevitability about the collages—that they had to be made this way and no other way.

IV.

For the most part, the paperboard supports came in two sizes, an elongated vertical rectangle (14 x 5 inches) and nearly square (10 x 7 inches). In the tall, narrow formats, Rauschenberg often affixed a smaller, similarly proportioned, buff-colored collage element near the top edge of the support, always attentive to the spacing on all sides.

These works each have at least three components to deal with—the shape and color of the support, the shape and color of the buff-colored paper, and the collage element, which could be an image, a diagram, or some form of writing. He might add something unforeseen, such as a strip of fabric, as well as pencil lines and glue.

Rectangles within rectangles within rectangles.There is something about the way one element floats within the other, its coloristic interaction with its surroundings, brings the paintings of Mark Rothko to mind. Even when all of the parts are visible, they are about something inside something inside something else.

When Rauschenberg stacks the collage elements within the narrower compositions, one gets the feeling that he started at the top and worked his way down. In the instances where he layers smaller components on top of the buff paper, he is always attentive to their placement in relation to the bottom layer, and to whether they are plain or printed. There is a tension between symmetry and asymmetry running throughout the collages, which contributes to their visual strength.

In the nearly square formats, Rauschenberg also seems to start at the top, often with a collage element that extends almost to the side edges, leaving a narrow border. In some cases, the placement of the printed and colored collage elements surround a central image, such as in Untitled [locomotive], c. 1952 (fig. 33).

Visually, the collages range from the austere and abstract to the densely packed, bristling with images and Arabic script. They are evocative without becoming narrative.

V.

Rauschenberg never framed these collages because he wanted the viewer to be able to hold and examine them, like pages from lost or forgotten books. He wanted someone to interact with them, to break the barrier separating art and life.

There are two central hinged panels in Untitled [pictographs and feathers], c. 1952 (fig. 2), which can be opened, revealing two brightly colored feathers inside, one red and one teal. In Untitled [Christian symbol], c. 1952 (fig. 18), there is a pocket near the top, below the Christogram (formed by superimposing the first two capital letters of the Greek spelling of Christ), with a piece of folded paper tucked inside.

These interactive collages share something with the artist’s small, boxed assemblages, such as Untitled (Scatole Personali), c. 1952 (fig. 25).This work, which prefigures the boxes of Lucas Samaras, is haunting, secretive, and threatening—full of intimations of mortality. Opening it, we encounter another kind of box, a fragment of a photograph of the artist, placed under a lens, all of which is partially covered with dirt.There are two rows of upward thrusting pins, one on either side of the photograph, protecting it, like sharp silent sentinels.Out of ordinary things Rauschenberg has assembled a reliquary containing his own disembodied image to be carried with him wherever he goes; a reminder of what accompanies us no matter how far we travel from home.

RELATED POSTS