튜린의 형이상학적 빛

Metaphysical Light in Turin

01

Text by 가이 다벤포트 Guy Davenport

Translation by 박상미 Mimi Park

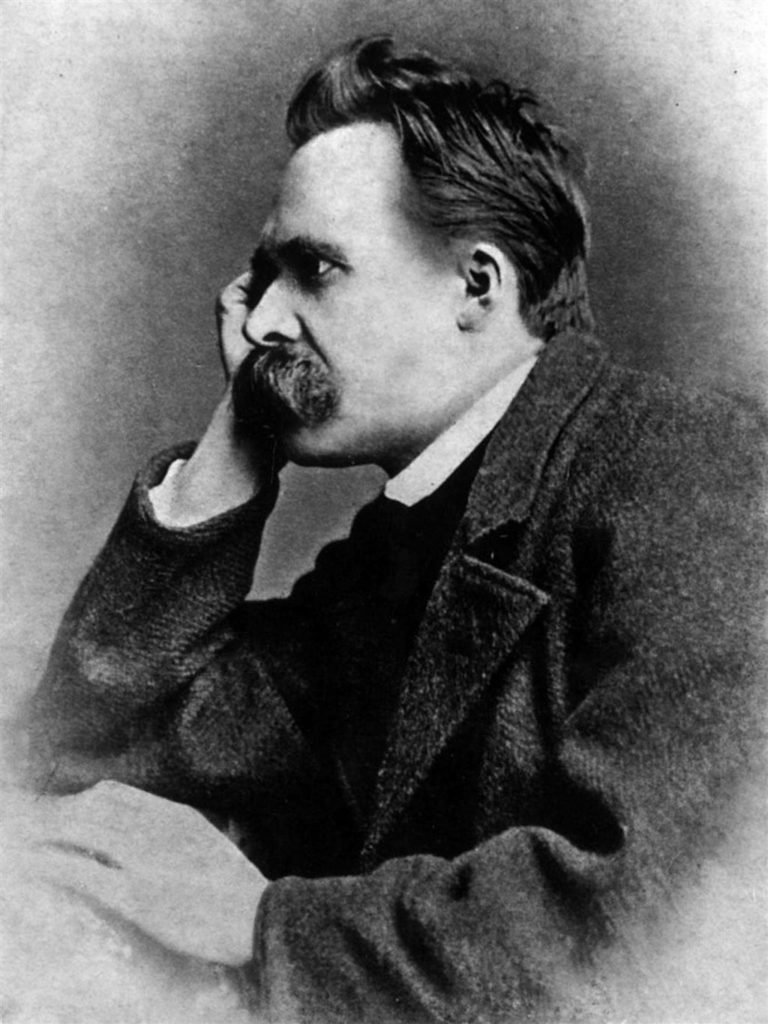

1888년 4월 7일 프리드리히 니체가 튜린에서, 죽기 전 10년 동안 정신 이상이 되기 전 마지막 몇 달을 그곳에서 보낼 때, 친구이자 조수, 음악가인 피터 가스트*에게 편지를 보냈다. “하지만... 튜린! 나는 지금 이 도시에 있어야만 하네!”

이건 분명한 사실이네. 처음 며칠은 정말 상황이 최악이었는데도, 처음부터 그렇게 느꼈어. 우중충하게 비가 오다가 바로 얼음이 얼 정도로 추워지니 신경에 정말 안 좋았지. 이따금씩 습하지만 따뜻할 때를 빼면 말이야. 하지만 얼마나 품위 있고 묵직한 도시인지 몰라! 내가 두려워했던 것처럼 대도시도 아니고 현대적인 도시도 아니고, 17세기의 웅장한 주거지역이라네. 이 도시가 갖는 주도적인 하나의 느낌은 왕실과 귀족의 그것이었어. 도시의 어딜 가나 귀족적인 고요함이 있고, 옹졸한 교외 동네는 없다네. 색채도 통일감이 있어. (도시 전체적인 톤은 황색과 적갈색이야) 게다가 보기에도 좋지만 걷기에도 좋은 도시라고! 버스와 트램을 말할 것도 없고 탄탄한 도보는 신기할 정도로 질서 정연하네. 얼마나 진중하고 웅장한 곳인가... 거리는 깨끗하고 잘 설계되어 있고, 내가 기대했던 것보다 훨씬 품격이 있다네. 내가 본 중 가장 아름다운 카페들이 있고, 이런 아케이드는 변화무쌍한 날씨 때문에 필요한 게 사실인데 공간이 꽤 넓어서 답답하지 않아. 포Po 다리 위에서 저녁 시간을 보내면― 선과 악을 초월해서, 환상적이라네!

튜린이라는 도시, 한 시대에서 그다음 시대로 변하고 있던, 19세기 이탈리아의 이 도시―우아하게 전차와 철로를 들여놓으면서도 고대 도시의 윤곽을 지키고, 광장과 공원에 기마상을 세우는, 교육과 도서관의 도시―에 대한 니체의 시각은 1889년 1월 3일 카를로 알베르토(실제로는 카리냐노) 광장에서 사라지게 된다. 이 광장에서 니체는 수레를 끄는 늙은 말이 잔인하게 채찍질 당하는 것을 본 순간, 말을 보호하려고 뛰어가 형제라 부르며 껴안으며 쓰러졌는데, 그 이후 영원히 제정신으로 돌아오지 못했다.

*피터 가스트 Peter Gast (1854-1918)

요한 하인리히 쾨셀리츠 Johann Heinrich Köselitz 독일의 작가, 작곡가. 니체의 오랜 친구였고, 니체가 그에게 피터 가스트라는 예명을 지어주었다.

니체가 쓰러졌을 때 게오르그 브라네스*는 덴마크에서 니체에 관한 수업을 강의하고 있었다. 1680년 구아리니Guarini가 세운 카리냐노 궁―1840년대에는 사르디니아 하원 건물이었고, 1860년대는 이탈리아의 국회였던―이 니체가 쓰러지는 것을 목격하듯, 이곳에 서 있었다. 이 건물은 니체가 튜린에 있을 당시에는 자연사 박물관으로 이용됐었다. 정문 앞에는 철학자 빈센조 지오베르티*의 동상이 세워져 있는데, 그는 키케로식의 커리어를 통해 현대 이탈리아라는 국가의 형태를 만든 장본인이다. 그의 삶이 공적이고 실질적이었다면 니체의 삶은 사적이고 보잘것없었다. 광장에는 카를로 알베르토 왕의 기마상이 또한 세워져 있는데, 이 동상은 그의 궁전과 함께 수발피나 갤러리의 일부가 되었다

*게오르그 브라네스 Georg Brandes (1842-1927)

덴마크의 문학비평가, 인문학자

*빈젠조 지오베르티 Vincenzo Gioberti (1801-1852)

이탈리아의 종교인, 철학자, 정치가

쓰러지기 전에 니체는 모든 역사와 그 의미는 자의적이라고, 우리 머릿속에서 지어낸 픽션이라고 결론 내렸었다. 우리가 확신할 수 있는 것은 다만 모든 사건이 일어나고 또다시 반복되어 일어난다는 것이다. 헤라클리투스가 말한 것처럼, 성격이 운명인 것이다. 눈먼 상태에서 변할 수 없고 고쳐질 수 없는 성격이 영원히 하나의 비극적인 운명 속으로 쓰러져 버린 것이다. 조이스가 <피네간의 경야>에서 말한 것처럼 “같은 것이 새롭게 반복된다.”

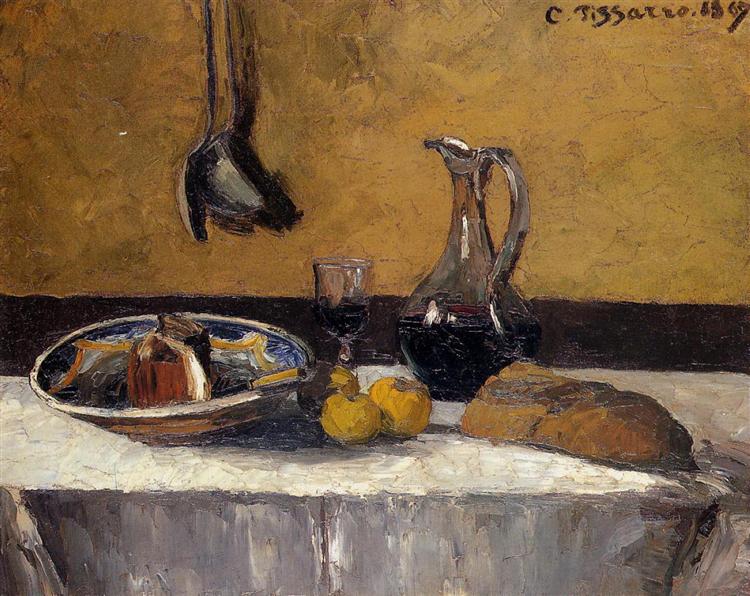

이 시기에 니체의 작업 책상에 대한 기록이 있다. 폴 드센*이 그의 자서전에서 니체가 튜린으로 가기 직전 실즈마리아로 그를 방문했던 일화에 대해 기술했었다. '(그의 한쪽 방에 있는) 가구들은 조촐했다. 한쪽으로 그의 책들이 있었는데, 내가 예전에 본 적이 있는 책들이었다. 그리고 커피잔과 계란 껍질, 원고 더미, 세면도구가 어지럽게 놓인 낡은 탁자, 그 아래에는 부츠잭이 끼워진 부츠와 아직 정돈되지 않은 침대가 있었다.'

튜린의 아름다움, 특히 맑은 가을날의 아름다움은 니체가 서신에서 여러 번 언급한다. 그는 튜린의 파란 하늘을 보면 생각이 정리되었다. 또 튜린이라는 도시의 기하학적 구성을 좋아했다. 고전적인 질서와 가지런함, 현대적인 활기까지. 그리고 그 모든 것이 멜랑콜리와 노스탤지어에 잠겨있었다

*폴 드센 Paul Deussen (1845-1919)

독일의 인도학자로, 쇼펜하우어의 영향을 크게 받았고 니체의 친구였다. 1911년 쇼펜하우어 회를 창립하고, 쇼펜하우어 연보를 발행하였다.

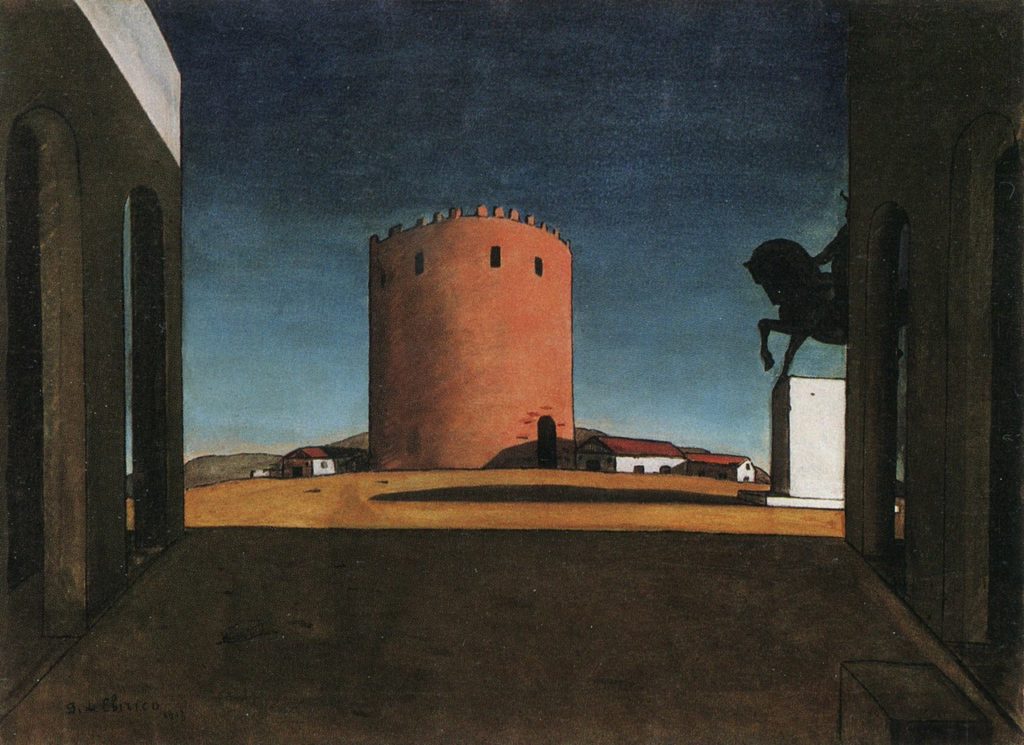

튜린에 대한 니체의 ‘되풀이되는 운명’에 관한 생각은 그리스계 이탈리아 화가인 조르지오 디 키리코*의 회화 작업의 영감이 되었다. 1960년대 키리코는 자서전을 쓰던 중 튜린의 거리의 중요성에 대해 니체가 한 생각을 보여주기 위해, 뮌헨에 독일 학생들을 데리고 오려던 것을 회상했다.

[디 키리코가 말하길] 나는 프리츠와 커트 가츠가 [니체의 철학적 관점들에 빠져있었음에도 불구하고] 그가 진정으로 발견한 것이 무엇인지 제대로 이해하지 못하고 있었음을 보았다. 이 발견이란 기이하고도 심오한 시정으로, 이는 무한히 신비롭고 고독한 정서로, 이는 슈티뭉stimmung[도덕적인 의미에서 “분위기”를 뜻하는 이 독일 말은 매우 유용하다] 에 기반한 것이다. 반복하지만 가을 오후의 슈티뭉, 즉 하늘은 청명하고 그림자는 여름보다 길어졌을 때의 분위기를 말한다. 이 특별한 정서는 제노아와 니스 같은 이탈리아와 지중해의 도시들에서 느낄 수 있다. (하지만 당연하게도 이런 정서를 느낄 수 있는 나의 특별한 능력을 갖는 행운이 따라주어야 한다.) 하지만 이런 현상이 일어나는 튜린 같은 이탈리아의 도시야말로 월등한 차이를 갖는다.

나중에 그는 자서전에서 “나는 니체의 책에서 발견한 이 강렬하고 신비로운 느낌―이탈리아 도시에서 느끼는 아름다운 가을 오후의 멜랑콜리―을 표현하려는 그림을 그리기 시작했다.”고 썼다.

디 키리코의 초기작은 피카소가 입체주의 시기와 필적할 정도의 성공적인 작업이었고, 그렇게 우리 시대 정서에 어필했다. 발레리의 표현에 따르면, 그의 그림은 우리 머릿속에 영구의 존재하는 가구의 일부가 되었다. 전형적인 그의 초기작에서 우리는 아케이드가 있는 이탈리아 도시 광장을 볼 수 있다. 하늘은 가을의 청색이고 그림자는 길다. 그림의 앞쪽에는 언제나 알 수 없는 사람들과 물건들, 커다란 아티초크나 굴렁쇠를 굴리는 소녀, 조각난 고전 조각상 같은 것이 있고, 뒤쪽에는 언제나 기차가 지나간다. 전체적으로 기이하고 알 수 없는 느낌을 준다. 나중에 기욤 아폴리네르가 디 키리코를 발견했을 때 그는 '초현실주의'라는 말을 처음으로 썼다. 이 말은 비이성적이고 꿈 같은 판타지를 말하는 것이 아니고(이 단어의 의미가 그렇게 되고 말았지만) 존재에 대한 형이상학적 자각이 너무나 강렬해서 마치 계시처럼 느껴지는 종류의 리얼리즘을 뜻한다. (계속)

*조르지오 디 키리코 Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978)

“1912년부터 1915년까지 내가 그린 연작들은 모두 튜린에서 영감을 받은 것이다. 내가 진정으로 고백하건대, 이 그림들은 또한 그즈음 내가 열렬히 읽던 프리드리히 니체의 영향을 받은 것이기도 하다. 그가 튜린에서 쓰러져 정신 이상이 되기 전에 집필한 “이 사람을 보라”를 통해 이 도시의 특별한 아름다움을 이해할 수 있게 되었다. 튜린의 형이상학적 우아함이 가장 잘 드러나는 진정한 계절은 가을이다.... 튜린이 내게 보여준 가을은 현란한 형형색색의 활기는 아니었지만 활기찼고, 가깝고 먼 시간의, 엄청난 정적과 순수를 간직한 거대한 것이다. 그것은 철학자, 그리고 철학적인 시인, 예술가들의 계절이었다.”

- 마우리지오 칼베시 Maurizio Calvesi (인용문은 조르지오 디 키리코가 1935년 불어로 쓴 원고에서 발췌되었다고 함)

On 7 April 1888, Friedrich Nietzsche, in Turin and in the last months of any lucidity of mind before the decade of insanity with which his life ended, wrote to his friend and amanuensis, the musician Peter Gast: “But Turin! . . . This is really the city which I can now use!”

This is palpably for me, and was so almost from the start, however horrible the situation was for the first days. Above all, miserable rainy weather; icy changeable, oppressive to the nerves, with humid, warm hours between. But what a dignified and serious city! Not at all a metropolis, not at all modern, as I had feared, but a princely residence of the seventeenth century, one that had only a single commanding taste in all things—the court and the noblesse. Everywhere the aristocratic calm has been kept: there are no petty suburbs; a unity of taste even in matters of color (the whole city is yellow or reddish brown). And a classical place for the feet as for the eyes! What robustness, what sidewalks, not to mention the buses and trams, the organization of which verges on the marvelous here. . . . What serious and solemn palaces . . . the streets clean and serious—and everything far more dignified than I had expected! The most beautiful cafes I have ever seen. These arcades are somewhat necessary when the climate is so changeable, but they are spacious一they do not oppress one. The evening on the Po Bridge一glorious. Beyond good and evil!

This vision of a nineteenth-century Italian city in transition between one age and another, keeping its ancient lineaments while gracefully incorporating electric trams and the railroad, erecting bronze equestrian statues in its squares and gardens, a city of libraries and learning, would come to an end for Nietzsche on 3 January 1889, in the Piazza Carlo Alberto*. Here he saw an old draft horse being cruelly beaten. He tried to defend the horse, embracing it and calling it brother, and in that moment his mind went dark forever.

When Nietzsche fell, Georg Brandes was giving a course of lectures on him in Denmark. As witness to his collapse, there stood around him the Palazzo Carignano, built in 1680 by Guarini, which had served as the Sardinian Chamber of Deputies in the 1840s and as the Parliament of Italy in the 1860s. In Nietzsche’s day it had become a museum of natural history. In front of it stands a statue of a philosopher, Vincenzo Gioberti, whose Ciceronian career had shaped the modern Italian state, whose life had been as public and practical as Nietzsche’s had been private and futile. The square also contained a bronze equestrian statue of King Carlo Alberto, together with his palace, which had been made into the Galleria dell'Industria Subalpina.

Before he fell, Nietzsche had come to the conclusion that all history and meaning were arbitrary, a fiction from our minds. All that we could be certain of was that every event would happen over and over again. Character, as Heraclitus had said, is fate; and man in his blindness and with the one unchanging and irredeemable character would stumble forever into the one tragic fate. The same anew, as Joyce would say in Finnegans Wake.

We have a description of Nietzsche’s worktable from this period. Paul Deussen in his memoirs recounts a visit with Nietzsche at Sils Maria, just before he went to Turin. “The furniture [of his one room] was as simple as could be. To one side, I saw his books, most of which were familiar to me from before, a rustic table with a coffee cup on it, egg shells, manuscripts, toilet articles, all in great disorder, which spread over a bootjack with boots attached, to the still unmade bed.”

The beauty of Turin, especially on clear autumn days, occurs in many letters of Nietzsche. A blue sky, he explained, collected his thoughts. He liked the geometry of the city. He saw classical continuities, orderliness, a modern briskness. And the whole was drenched in melancholy and nostalgia.

Nietzsche’s vision of recurring fate in Turin was to become the inspiration for the painting of the Greek-Italian painter *Giorgio De Chirico. Writing his memoirs in the 1960s, De Chirico remembered trying to get German students in Munich to understand the significance of the streets of Turin in Nietzsche’s thought:

I observed [De Chirico says] that Fritz and Kurt Gatz [though obsessed by the philosophical ideas of Nietzsche] had not in fact understood what constituted the true novelty discovered by [him]. This novelty is a strange and profound poetry, infinitely mysterious and solitary, which is based on the Stimmung (I use this very effective German word which could be translated as atmosphere in the moral sense), the Stimmung, I repeat, of an autumn afternoon, when the sky is clear and the shadows are longer than in summer. . . . This extra-ordinary sensation can be found (but it is necessary, naturally, to have the good fortune to possess my exceptional faculties) in Italian cities and in Mediterranean cities like Genoa or Nice; but the Italian city par excellence where this extraordinary phenomenon appears is Turin.

And later in these memoirs: “I [began] to paint subjects in which I tried to express the strong and mysterious feeling I had discovered in the books of Nietzsche: the melancholy of beautiful autumn days, afternoons in Italian cities.”

De Chirico’s early work has entered the sensibility of our time with a success equaled only by that of Picasso in his cubist period. It has, in Valery's phrase, become part of the permanent furniture of our mind. In a typical De Chirico we see an Italian square, with arcades. The sky is autumnal blue, the shadows are long. In the foreground there is always an array of unaccountable figures and objects, large artichokes, or a girl playing with a hoop, broken classical statuary, and in the background the inevitable train. The general effect is one of enigma. Later, when Guillaume Apollinaire discovered De Chirico, he invented the term surrealism, to indicate not irrational, dreamlike fantasy (as the word has come to mean) but realism so charged with a metaphysical awareness of being that it is a revelation.

*

Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978)

“It was Turin that inspired all of the paintings in the series I painted from 1912 to 1915. I truthfully confess that they also owe much to Friedrich Nietzsche of whom I was a passionate reader at the time. His Ecce homo, written in Turin shortly before falling into madness, greatly helped me understand the particular beauty of this city. The real season for Turin, during which her metaphysical grace reveals itself best, is Autumn; an autumn which has nothing in common with the romantic autumn, with the sky littered with clouds, with dead leaves and the departure of swallows. The autumn which Turin revealed to me is cheerful, even if it is certainly not a striking and multicoloured cheerfulness. It is something immense, of a time near and far, of a great serenity and a great purity. It is very close to the joy which a convalescent experiences when he comes through a long and painful disease. It is the season of philosophers, poets and artists inclined to philosophise."

—-in a text written in 1935 French by Maurizio Calvesi

RELATED POSTS