튜린의 형이상학적 빛

Metaphysical Light in Turin

02

Text by 가이 다벤포트 Guy Davenport

Translation by 박상미 Mimi Park

디 키리코의 회화적 세계는 에니그마 enigma*이다. “에니그마 enigma”는 그가 사용한 단어이고, 니체도 이 말을 사용했다. 환상이 배재된 세상, 그에 대한 맹목적인 수용은 그의 그림에서 하나의 에니그마, 수수께끼 riddle* 가 되고, 현실의 본질에 대한 모든 질문들을 전반적으로 다시 묻게 한다. 디 키리코와 그의 학파, 카를로 카라, 지오르지오 모란디—그리고 이들을 따른 막스 에른스트, 르네 마그리트, 오토 딕스, 오스카 슐레머— 등은 스스로를 형이상학파라고 불렀다.

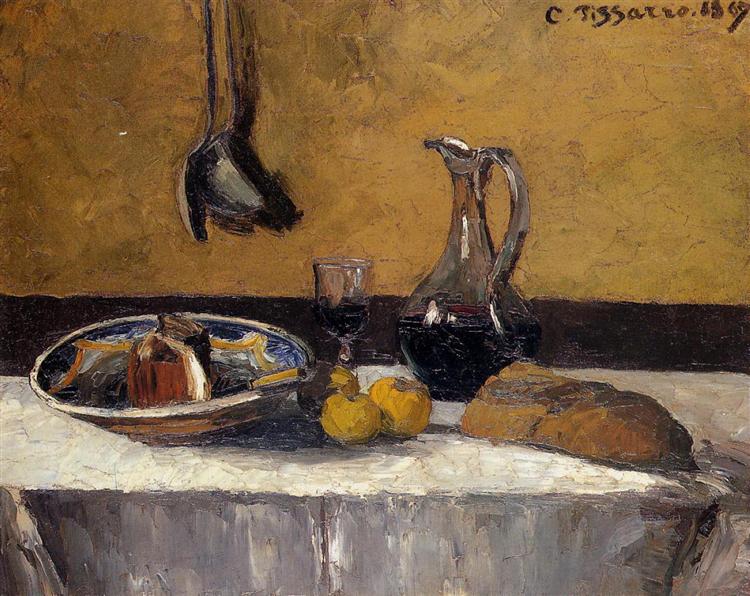

영국의 형이상학파 시인들처럼, 이들은 탄생은 과학이 그 기본적인 전제를 재검토하는 시기와 일치한다. 존 던*에게 지도와 나침반이 있었던 것처럼, 철학적 명상이 깃든 정물은 그들에게 걸맞는 표현수단이었다.

디 키리코의 개성이 가장 뚜렷하게 드러난 그림들을 보면 종종 정물과 풍경이 함께 있다. 그즈음 제임스 조이스도 “율리시즈”에서 비슷한 일을 하고 있었다. 특히 레스트리고니언즈 Laestrygonians 장*에서 블룸이 점심식사를 하는데, 상징적인 정물의 장면들이 서사적인 구조와 맞물리고, 더 나아가서는 건축의 개념으로 엮어진다.(건축은 이 챕터의 “예술”에 해당하는데, 이 내용은 조이스가 리나티를 위해 만들어준 “도표”* 속에 있다) 건축과 음식은 다양한 방식으로 조화를 이룰 수 있다. 우리는 건물에 수확한 과일의 화환을 돌로 새겨 장식한다. 조이스는 이 챕터의 도입을 “파인애플 록, 레몬 플랫, 버터 스캇치”라고 상점의 쇼윈도우에 전시된 사탕의 이름을 나열하며 시작하는데, “파인애플 록 Pineapple Rock”은 또한 “돌로 만든 파인애플” 즉 신고전주의 석조 건물의 코니스에 환대의 의미로 들어가는 장식을 뜻할 수 있다.

진실을 보는 한 가지 방법은 대상을 전에 한 번도 본 적이 없는 것처럼, 익숙한 것을 에니그마 enigma처럼 보는 것이다. 무언가를 알기 위한, 이러한 “낯설게 하기”의 기법은 디 키리코의, 그리고 조이스의 동시대 작가들인 오십 만델스탐*과 빅터 쉬클로브스키*의 방법론이었다. 만델스탐은 그의 짧은 소설들과 긴밀한 구성의 시들에서 인벤토리(자신의 아버지의 책꽂이에 꽂힌 책들의 목록, 즉 조이스가 블룸의 책들을 나열하는 것처럼)와 긴 목록들(그의 학교 친구들의 이름들이나 컬렉터들의 집에 있는 가구들을 나열하는)을 적곤 하는데, 이는 디 키리코가 튜린이라는 도시의 구성물들을 마구 섞어 놓거나 낯선 방식으로 나열하는 것과 유사하다고 할 수 있다.

이제 우리는 키이츠의 정물을 운명을 살펴보자. 그의 정물의 감각적인 명료함이 파라데이*와 마르코니* 시대에 어떻게 재조명될 수 있는지. 그런 다음 셸리의 철학적 정물을, 디 키리코의 형이상학적 그림들과 우리 시대의 모든 수수께끼 같은 정물에 선행하는 대표 선언문으로서 보아야 한다.

우리는 밀턴을 통해 키이츠에 다가가야 한다:

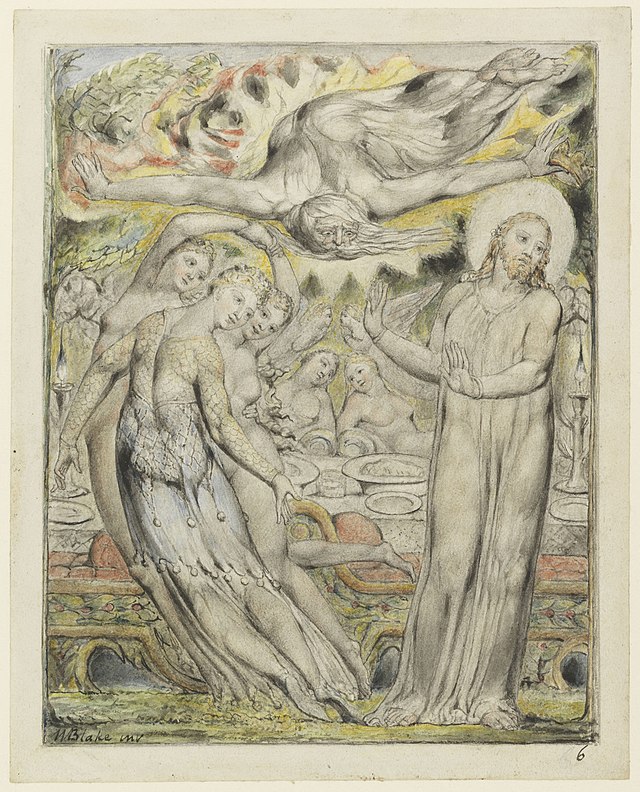

<복낙원 Paradise Regained>* 에서 광야에서 40일을 단식한 예수가 실제 배고픔보다 “아버지의 뜻에 따르는 일에 더 굶주려서” 어쨌든 “식욕은 꿈을 꾸게 하므로” 엘리야가 까마귀들에 날라다 준 음식을 먹는 꿈을 꾸거나 “다니엘과 함께 손님으로 콩과 채소를 먹는 꿈”을 꾸었다. 잠에서 깨자 예수는 사탄을 만나게 되고, 사탄은 다음과 같이 단식을 깰 것을 권유한다.

아주 넓은 차양 밑 널찍한 공간에

호화로운 식탁이 궁궐처럼 차려져 있다.

요리가 쌓여있고, 최상급의 맛 좋은 고기류,

사냥에서 잡은, 반죽을 입혔거나 쇠꼬챙이에 꽂아 구운,

또는 용연향에 쪄낸 짐승과 새고기, 바다나 해안,

또는 민물, 소용돌이치는 시내에서 잡은 어류와 조개들,

폰토스*나 루크린만* 또는 아프리카의 해안에서 말린

진귀한 이름의 것들. 아, 이런 진미에 비하면

이브를 꾄 저 야생의 사과는 얼마나 소박했던가!

밀턴의 익힌 요리와 날 것의 대조는 그의 시대에 존재하던 개신교의 단순한 생활과 가톨릭의 호화로움, 농가와 성, 정절과 관능 사이의 긴장을 나타낸다. 하지만 당시 예술은 바로크였고, 강렬한 대조가 가능한 형태였다. 성서와 그리스 신화의 조합은 바로크의 공식이 되었고, 바하의 미사 음악(그리스 합창과 로마식 카덴스, 아라비아의 악기, 기독교의 가치관에 바탕한), 라신의 <페드르 Phedre> (두 개의 신화가 운율을 이루듯이 연결되어 있다. 하나는 히브루어, 하나는 그리스어로, 라틴 사투리가 베르길리우스의 언어처럼 정교한 어법과 자유로운 표현으로 세련되게 표현되었다.) 그리고 밀턴의 <투사 삼손> (유태인의 설화와 그리스 희곡이 잘 조화된 작품으로, 이 작품을 보면 르네상스란 결국 성서와 그리스 시의 조합, 그 이상도 이하도 아니라고 느껴질 정도다) 이 그 좋은 예이다.

호화로운 식기대, 향기로운 냄새를 풍기는 와인 옆에 가니메데스*나

힐라스*보다도 더 화색이 좋은, 화려하게 차려입은

날씬한 젊은이들이 질서정연하게 서있다.

좀 떨어져 나무 밑에는 디아나를 모시는 요정들과

아말테이아의 뿔에서 난 꽃과 과실을 든 나이아스들,

그리고 옛이야기나 그후 전설에 나오는

로그레스나 리오네스의 기사들인 랜슬롯, 펠레아스,

또는 펠레노어가 넓은 숲속에서 만났다는

선녀들보다도 더 아름다워 보이는 헤스페리데스의

여인들이 때로는 춤을 추기도 하고 때로는

서 있기도 했다. 그러는 동안 조음이 고운

현이나 매력적인 피리의 노랫가락이

들렸고, 부드러운 바람은 그 포근한 날개로

아라비아의 향기와 플로라의 이른봄 향기를 풍겼다.

이 열여섯 줄은 와인 냄새로 시작해서 꽃의 향기로 끝을 맺는다. 밈네르모스 Mimnermus*나 일리아드에서 보이는 고전적인 좌우대칭은, 한쌍 diptych으로 변화되었다. 즉 글의 중간 쯤, 한쪽에는 가니메데스와 힐라스가, 다른 쪽에 중세 연인과 기사들이 등장한다. 그 다음에 님프와 요정이 좌우대칭으로 등장한다. 중간에는 북구의 숲과 세상 끝의 상상의 섬들이 뒤섞여있다. 그 행로는 동쪽에서 서쪽으로 나아가고 중간에서 동쪽으로 다시 튼다. 밀턴의 정물(화려한 네덜란드 프롱크스틸레벤과 카라바지오, 조르지오네와 유사하다고 할 수 있는)에서의 패턴은 이 장르의 암시적인 가능성을 잘 보여준다. 장소특정적이고, 정확하고, 구체적이어서 다른 곳에서 날아들어온 상징물들의 안식처 같은 느낌을 주며 시간과 공간을 우아하게 담아낸다. 밀턴의 행로 passage는 내가 말한 것보다도 훨씬 광범위하게 펼쳐질 수 있다.

*enigma의 사전적 정의는 수수께끼로, 질문을 일으키는, 알 수 없고 신비로운 상태의 것이나 사람을 말한다.

*riddle: 풀기 어려운 질문, 난제

*존 던 John Donne (1572-1631)

영국의 시인, 학자, 군인, 관료로서, 대표적인 형이상학파 시인으로 알려졌다. 그는 서로 관계없는 것들을 연결시키는 것과 같은 ‘형이상학적 장치metaphysical conceit’에 능했는데, 이를테면 연인의 관계를 나침반의 바늘에 비교하는 식이었다.

*율리시즈의 8번 째 에피소드로 블룸이 점심시간에 펍pub에서 식사하는 장면, 그가 먹는 음식들이 묘사된다.

*친구 카를로 리나티의 이해를 돕기 위해 조이스가 제작한 이 도표는 각 챕터마다 그에 해당하는 시간, 색, 사람들, 과학/예술, 의미를 해제처럼 달아놓았다. 여기서 저자가 언급한 챕터 “레스트리니언즈”에 해당하는 “예술”은 건축이다.

*오십 만델스탐 Ossip Mandelstamm (1891-1938)

20세기를 대표하는 러시아와 소련의 시인으로, 시대를 풍미하던 상징주의에서 벗어나 신고전주의로 향하던 아크메이스트Acmeist 시인으로 일컬어진다.

*빅터 쉬클로브스키 Victor Shklovsky (1893-1984)

러시아와 소련의 문학이론가이자 비평가로, 20세기 가장 중요한 문학, 문화 이론가로 칭송되며, 문학이론에 “낯설게 하기" 기법을 들여놓은 것으로 알려져 있다.

*마이클 파라데이 Michael Faraday (1791-1867)

영국의 물리학자이자 화학자로 전자기학과 전기화학 분야에 큰 기여를 남겼다.

*굴리엘모 마르코니 Guglielmo Marconi (1874-1937)

이탈리아의 발명가이자 전기공학자. 무선 전신을 발명, 실용화했고, 1909년 노벨물리학상을 공동수상했다.

*실낙원이 사탄의 유혹에 넘어가 아담과 이브가 낙원을 상실한다는 내용인 반면, 복낙원은 예수 그리스도가 사탄의 유혹을 이겨내고 잃어버린 낙원을 찾는다는 내용이다.

Adriaen van Utrecht, Banquet Still Life, 1644

*가니메데스Ganymede

제우스가 시동으로 삼기 위해 납치해 간 미소년

*힐라스Hylas

헤라클레스가 사랑한 미소년

*밈네르모스Mimnermus

고대 그리스의 서정시인으로, 기원전 630-600년에 활발할 활동을 했다.

It is, this vision of De Chirico’s, an enigma. That is his own word. It is also Nietzsche’s word. The world deprived of illusion and unthinking acceptance is reduced to an enigma, a riddle, a comprehensive re-asking of all questions about the nature of reality. De Chirico and his school—Carlo Carrà, Giorgio Morandi, and later by emulation Max Ernst, Rene Magritte, Otto Dix, Oskar Schlemmer—called themselves i metafisici. Like the English metaphysical poets, they came at a time when science was revising basic tenets. And as for Donne with his maps and compasses, the still life of philosophical meditation was a vehicle congenial to them.

De Chirico, in his most characteristic canvases, was fusing still life and landscape. Joyce, at about the same time, was doing the same thing in Ulysses. The chapter called the Lestrygonians, in which Bloom has lunch, is a series of symbolic still lifes fitted into a narrative structure that is moreover organized around the idea of architecture (the chapter's “art,” as Joyce designated in the schema he made for Linati). Architecture and food come together in various ways. We ornament buildings with garlands of harvest fruit in stone. Joyce’s opening words in this chapter, uPineapple rock, Lemon Platt, Butter Scotch,55 describe a display of sweets in a shop window, but pineapple rock is also a stone pineapple, as on the cornices of neoclassical buildings, a symbol of hospitality.

One way of recognizing verities is to look at them as if you had never seen them before, to make an enigma of the familiar. This “estrangement” of reality, in order to know it at all, was the program of De Chirico’s and Joyce's contemporaries Osip Mandelstam and Viktor Shklovski. Mandel stam in his terse novels and tightly wrought poems manipulates the inventory (as of his father’s bookshelf, like Joyce cataloging Bloom’s books) and the exhaustive list (as of his schoolmates, or the furnishings of an aesthete's rooms) much as De Chirico explores the reality of Turin by dislocating it, arranging it into unfamiliar conjunctions.

Let us look, now, at the fate of a still life in Keats and how its sensual brightness can be reseen in the age of Faraday and Marconi, and then at a philosophical still life by Shelley, as a first statement of the metaphysical art of De Chirico and all the enigmatic still lifes of our century. We must approach Keats through Milton:

In Paradise Regained, Christ, having fasted in the wilderness for forty days, “hung’ring more to do [his] Father’s will” than from “the sting of Famine,” dreamed, “as appetite is wont to dream,” of Elijah fed by ravens, “Or as a guest with Daniel at his pulse.” Waking, he meets Satan in a grove, who invites Him to break his fast, displaying

In ample space under the broadest shade

A Table richly spread, in regal mode,

With dishes pil’d, and meats of noblest sort

And savour, Beasts of chase, or Fowl of game,

In pastry built, or from the spit, or boil’d,

Gris-amber-steam’d; all Fish from Sea or Shore,

Freshet, or purling Brook, of shell or fin,

And exquisitest name, for which was drain’d

Pontus and Lucrine Bay, and Afric Coast.

Alas how simple, to these Cates compar’d,

Was that crude Apple that diverted Eve!

Milton’s contrast between the cooked and the raw is the tension of his age between archaic Protestant simplicity and Catholic luxury, between farm and castle, chastity and sensuality. The art, however, is baroque, and feeds on both terms of its tense contrast. That fusion of Bible and Greek myth constitutes the formula for the baroque, exemplified in Bach’s masses (Greek chorus, Roman cadences, arabic musical instruments, Christian mythos), Racine’s Phédre (two myths, rhyming in analogue, one Hebrew, one Greek, in a provincial dialect of Latin refined to a precision of diction and elasticity of expression that rivals those of Virgil), and Milton’s own Samson Agonistes (where Jewish folktale and Greek theater are so harmoniously joined that we feel that the word renaissance should never mean anything other than the cooperation of the Bible with Greek poetry):

And at a stately side-board by the wine

That fragrant smell diffus'd, in order stood

Tall stripling youths rich-clad, of fairer hue

Than Ganymede or Hylas; distant more

Under the Trees now tripp'd, now solemn stood

Nymphs of Diana's train, and Naiades

With fruits and flowers from Amalthea’s horn,

And Ladies of th’ Hesperides, that seem’d

Fairer than feign’d of old, or fabl’d since

Of Fairy Damsels met in Forest wide

By Knights of Logres, or of Lyones,

Lancelot or Pelleas, or Pellenore;

And all the while Harmonious Airs were heard

Of chiming strings, or charming pipes, and winds

Of gentlest gale Arabian odours fann’d

From their soft wings, and Flora’s earliest smells. These sixteen lines begin with the odor of wine and end with the fragrance of flowers. With archaic symmetry like that of Mimnermus or the Iliad, they resolve into a diptych. Next in toward their center we find Ganymede and Hylas on one side, medieval lovers and knights on the other. Then a symmetry of nymphs and fairy damsels. The median is a blur of northern forests and imaginary islands at the end of the world. The passage ako moves from east to west, turning at midpoint eastward again. Such patterns in Milton’s still life (analogous to gorgeous Dutch pronkstillleven and the richness of Caravaggio and Giorgione) show the allusive versatility of the genre. Local, exact, and palpable, it makes a nest of symbols flown in from elsewhere. It couches time and space in an elegance. Milton's passage will admit of far more extensive unfolding than I have suggested.

RELATED POSTS