부서진 두상: 재생의 선언

The Head as Fate

01

Text by 가이 다벤포트 Guy Davenport

Translation by 박상미 Mimi Park

도시인에게는 설화가 있다. 설화는 전설과 우화의 에너지와 함께 풍성하게 번성해왔고, 아마도 자연스럽고 무의식적인 방식으로 정물이라는 장르에 내재된 상징들을 사용하게 되었을 것이다. 설화의 매개체로서 출판물이 그 시작이었다면 영화, 라디오, 텔레비전 등이 그 뒤를 이었다. 도시의 설화라고 하면 예를 들어 돈키호테, 셜록 홈즈, 타잔 등을 말하는 것이다. 여기 등장하는 인물들은 그 텍스트로부터의 분산(또는 확산)이 빠르게 일어나며 다른 작가들도 차용하고, 그래서 등장 인물로서 그들의 실제 위치는 일반 대중의 상상 속에 있다고 할 수 있다. 텍스트는 이들 이야기의 원천, 또는 이들의 현실을 파악하기 위한 고전적인 레퍼런스로 작용할 뿐이다.

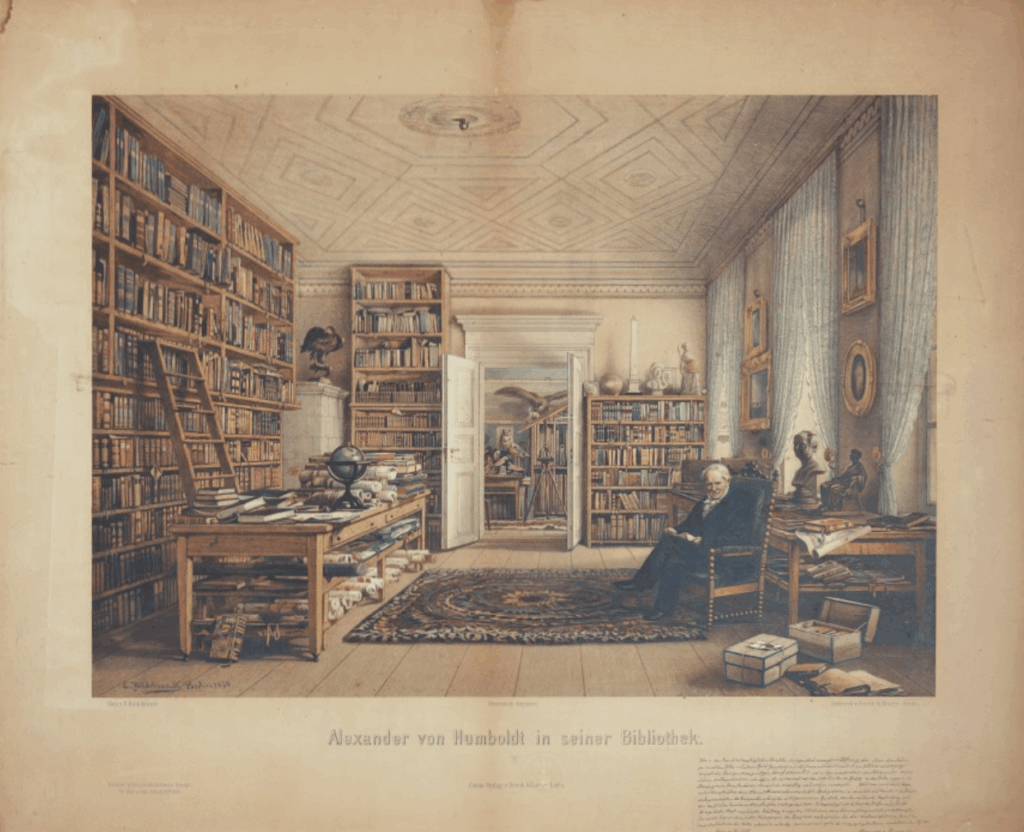

셜록 홈즈의 집이 221B 베이커 스트릿이라는 것은 누구나 알고 있다. 그의 집에는 화학 기구들이 놓인 탁자가 있다. 바이올린, 그리고 범죄 관련 신문기사를 모아놓은 스크랩북들이 있고, 벽난로 위에는 홈즈가 담배잎을 넣어놓는 페르시아 슬리퍼가 잭나이프로 고정되어 있다. 이 방은 애드가 앨런 포우의 단편 <어셔 가의 몰락>의 로데릭 어셔의 방, 그리고 홈즈의 전신이라 할 수 있는 탐정, 오귀스트 뒤팽의 방에 그 기원을 둔다. 더 깊은 의미에서 이 방은 리 헌트Leigh Hunt*의 방에서 시작한다. 존 키이츠가 리 헌트의 오두막에서 머물 때 “잠과 시Sleep and Poetry”를 쓴 것으로 유명한데, 헌트의 실내는 철학자, 시인의 서재요, 감성과 예민함을 간직한 사람의 은신처를 상징한다. 마리오 프라즈Mario Praz*의 인테리어 연구를 보면—포우의 가구 철학에 관련한 에세이들에서 기원한 연구—우리는 그런 방들을 다수 발견하게 된다. 괴테, 알렉산터 본 훔볼트, 퀴비에 등 과학자, 시인, 딜레탕트, 컬렉터, 온갖 다양한 것들을 사랑한 아마추어의 방들이 그것이다.

홈즈의 방에는 한때 오스카 뮤니에가 조각한 자기 자신의 흉상이 있었다. 이는 홈즈의 생명을 위협하는, 소리 없는 공기총 사격을 피하기 위해 홈즈의 모습을 위장하기 위했던 것으로 기억한다. 즉 홈즈가 동시에 두 군데 장소에 있게 하기 위한 책략이었다. 그러나 이는 그런 종류의 정물을 완성시키는, 탁자 위에 올려놓아야 할 필수품 같은 품목이기도 했다.

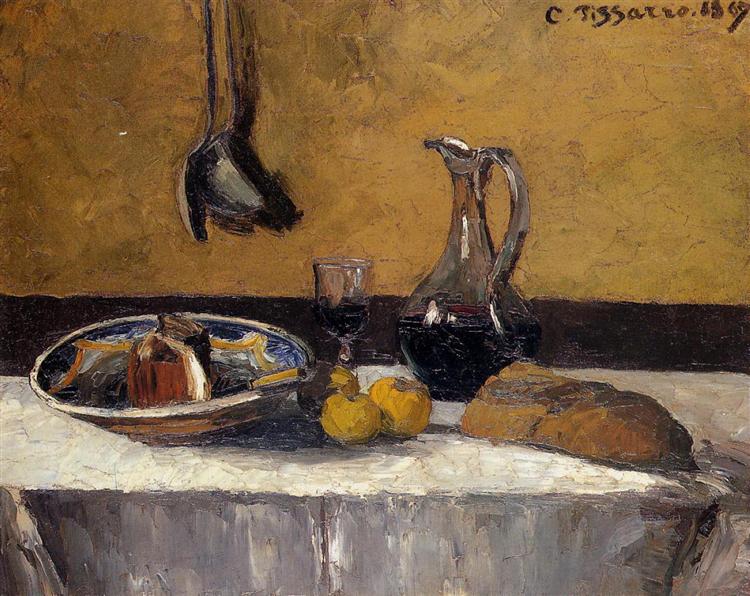

이런 전형적인 정물에는 책들과 철학적인 사색에 필요한 물건들—파이프, 악기(홈즈의 경우는 바이올린, 로데릭 어셔의 경우는 기타, 소로Thoreau의 경우는 플룻이었다. 월덴 호수에 있던 소로의 탁자 위에는 그리스어로 된 일리어드 한 권과 돌, 잎사귀, 그리고 플룻이 있었다.), 와인 잔과 와인 병(홈즈의 경우는 커피 또는 찻주전자였고, 와인은 그가 사건을 해결한 경우 축하 저녁을 들 때 놓여졌다), 그리고 고전적인 흉상이 등장한다.

이런 정물들에서 우리는 이 시대에 정물화라 여겨지는 청사진과 함께, 피카소와 브라크의 전형적인 큐비즘 정물화의 구성을 보게 된다. 이런 탁자 위 구성은 책들과 사자가 있던, 중세 전통의 성 제롬의 서재까지 거슬러 올라가는 것도 가능하다.

하지만 일단 홈즈의 흉상으로 돌아가보자. 그 흉상을 만든 인물, 오스카 뮤니에는 홈즈의 선조인 프랑스의 화가 호레이스 베르네와 같은 실제 인물을 모델로 했을 수 있다. 하지만 이름은 코난 도일이 지어낸 것이고, 그 이름은 동시대 벨기에 조각가인 콘스탄틴 뮤니에에서 따온 것일 가능성이 크다. 그는 흉상을 조각했고, 그의 친지이자 동료 소설가인 오스카 와일드는 <도리안 그레이의 초상>에서 그 모델이 겪어야할 운명의 고통을 예술 작품이 대신해서 겪는 이야기를 썼다. 홈즈의 흉상이 그를 대신하여 죽는 것과 다르지 않다.

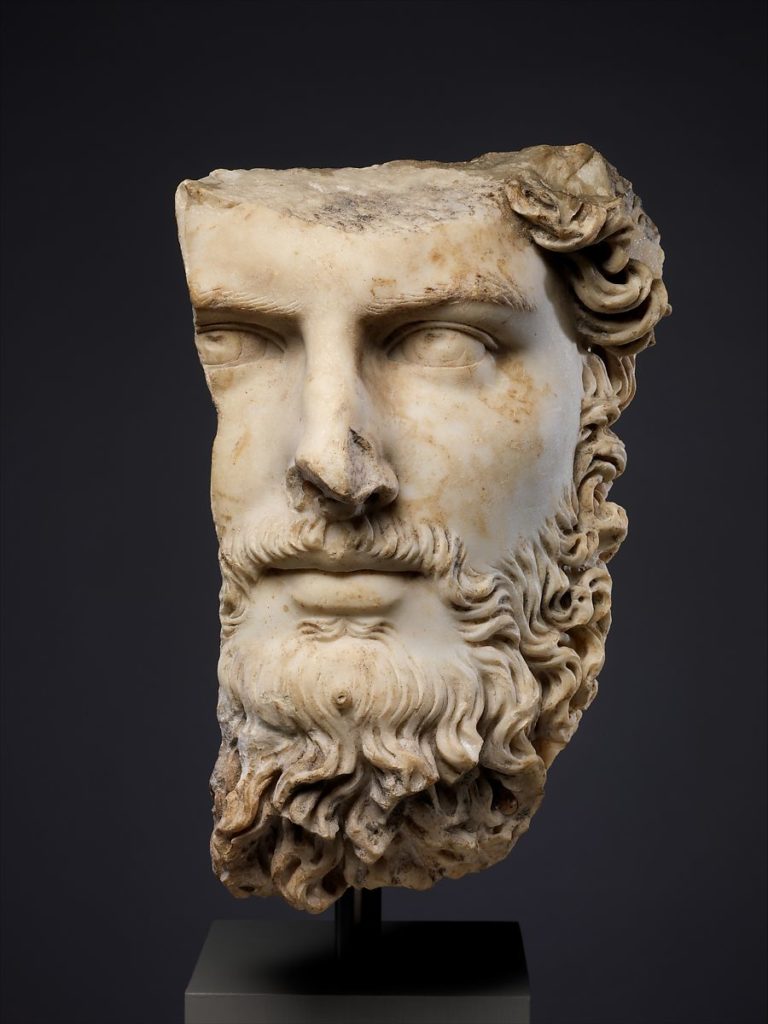

흉상을 부수는 내용이 담긴 홈즈의 이야기는 그 전에도 있었고, 창가에 형상을 놓아 누군가를 속인다는 내용도 <너도밤나무 집>에 나왔었다. <여섯 개의 나폴레옹 형상>에서는 누군가 대량 생산된 나폴레옹의 흉상을 연속해서 부순다. 범인은 석고 흉상이 공장에서 덜 굳었을 때, 그 속에 보르지아 가의 흑진주를 감추었었고, 감춘 흑진주를 찾아내려 한 것이 사건의 전모였지만, 정물이라는 아이콘의 일부가 폭력으로 파괴된다는 상징이 남겨지고, 우리는 그 이유가 궁금하다. “선반 위에 다른 작품들과 함께 놓여있던 나폴레옹의 석고 흉상이 산산조각으로 부서졌다.”고 묘사되었는데, “산산조각으로 부서졌다”는 부분이 흥미롭다. 지난 백 년 동안 고대 미술은 박물관과 미술관에 조각조각 부서진 모습으로 등장해왔다. 부서진 파편은 바로 과거라는 상태, 그 조건 자체이다. 이 파편들을 로마인들이 한 것처럼, 혹은 18세기에 그 전통을 이어받아 한 것처럼, 왁스로 붙여 수리해야 할 것인지 논쟁이 지속된다.

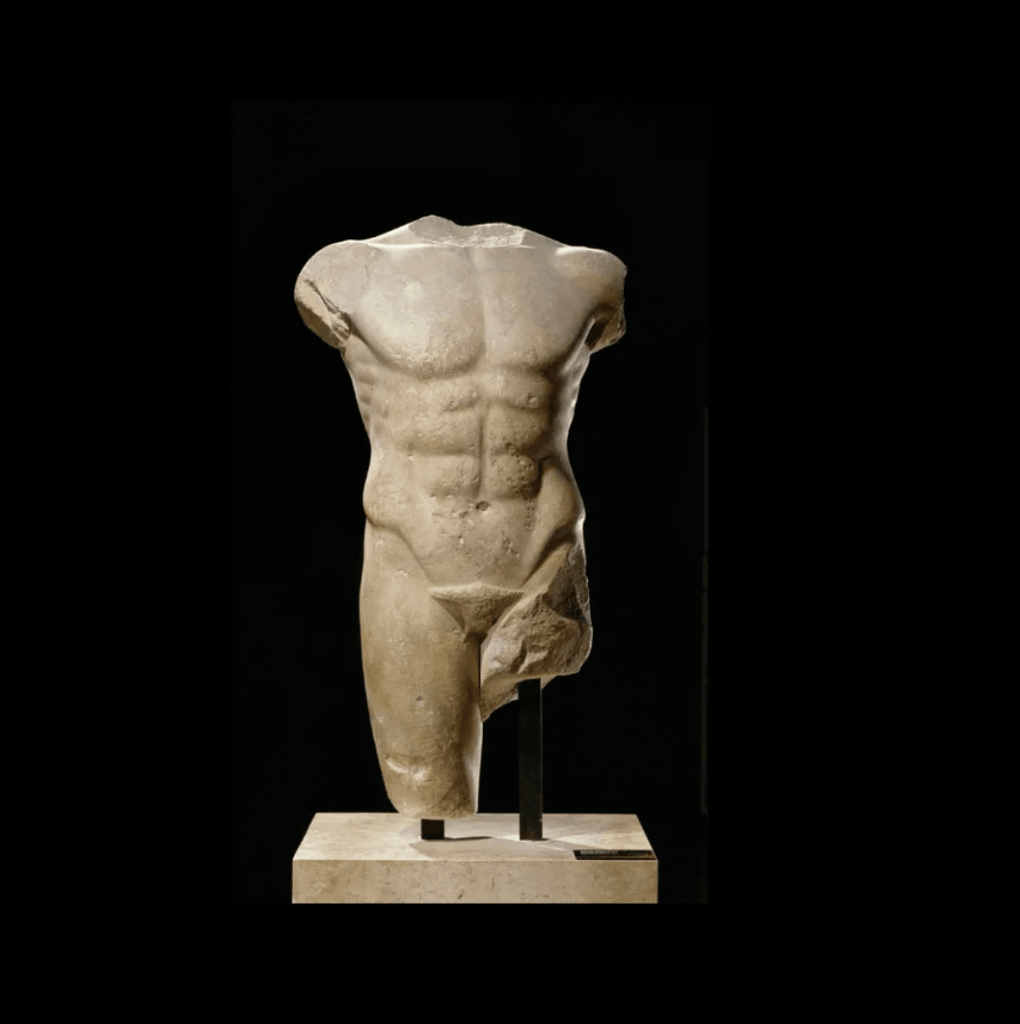

아니면 이 파편들을 유적 속에 그대로 남겨두자는 설득력있는 반론이 있으려나? 우리는 1768년 살해된 운동선수의 토르소에 관한 연구를 하던 빙켈만에서 “고대 아폴로의 토르소”를 쓴 릴케까지, 부서진 조각을 선호하는 경향을 추적해볼 수 있다. (에즈라 파운드가 “파피루스”에서 미완성의 고전 텍스트를 간직하는 것이 그를 복구하는 것보다 값지다고 한 것처럼)

릴케의 시는 이 부서진 조각상을 받아들이는 하나의 방식이다.

명철하게 앞을 보는 두 눈이 빛나던

그의 아름다운 머리를 우리는 알 수 없지만,

지금도 그 토르소는 샹들리에처럼 빛나고,

그의 응시는 그 안에서 조도를 낮추었을 뿐, 죽지 않고,

그대로 남아 불타고 있다. 그게 아니라면,

어떻게, 부풀어오른 가슴이 눈을 멀게 하고,

허벅지를 살짝 비틀 때마다 피어나는 미소는

씨앗이 모이는 중심을 향해 돌아오는가?

그게 아니라면, 이 돌은 이토록 탄탄하게 서있지 못하고,

두 어깨의 반짝이는 폭포수 아래,

그 야수의 우아함으로 빛나지 못하리라.

그리고 몸의 틈새마다, 별들로 가득한 하늘이 빛나듯

그리 드넓게 터져 빛나지도 않으리라. 여기서 너를 보고 있지 않은

부분은 어디에도 없기에, 너는 너의 삶을 바꿔야 한다.*

이 고대 그리스의 토르소를 보는 또 다른 방식이 있다면 그건 콘스탄틴 브랑쿠시의 “젊은 남자의 토르소”이다. 이 작품은 아주 곱게 갈아 광을 낸, 통나무 형태인데 브랑쿠시는 이에 그보다 훨씬 짧은 두 개의 몸통을 덧붙여 엉덩이뼈에서 가랑이까지 두 쪽으로 갈라진 다리처럼 형상화하였다. 금욕적인 무성의 형태이자, 빛나도록 단순한, 남자아이의 토르소이다. 브랑쿠시는 토르소의 개념을 가장 고대적인 형태로 환원한 것으로, 사람의 형상을 언제나 주변에 있는 통나무에서 만들었을 때, 아프리카에서 나무를 깎아 만든 조각을 연상시키고, 또한 그 형태의 환원이나 단순한 우아함에서 키클라데스*의 조각과의 연관성을 추측할 수 있다.

위대한 현대의 조각가가 셜록 홈즈 이야기 속의 이탈리아의 범죄자가 저지른 일을 완성시킨다는 식으로 말하니 이상하지만, 이게 실제로 일어나고 있는 일이다. 우리는 언제나 포우를 믿을 수 있듯 코난 도일도 믿을 수 있다. 조각이 영구적인 황화 현상을 겪고 있다는 도일의 생각은 정확했다. 그는 “바니콧 박사는 나폴레옹의 열렬한 지지자였고, 그의 집은 이 프랑스 황제의 책들과 사진들과 유물들로 가득했다.”고 적고, “켄징턴 가에 있는 집, 그의 현관에 프랑스의 조각가 드빈의 유명한 나폴레옹 두상이 있었고, 그리고 로어 브릭스턴에 있는 그의 병원 벽난로 위에 두상이 또 한 개 있었다.”고 했다. 이 흉상들을 부순 범인이 죽은 후 그의 주머니 속에서 이런 것들이 발견됐다. “사과, 줄, 1실링 짜리 런던 지도, 그리고 사진 한 장”이 그것이었다.

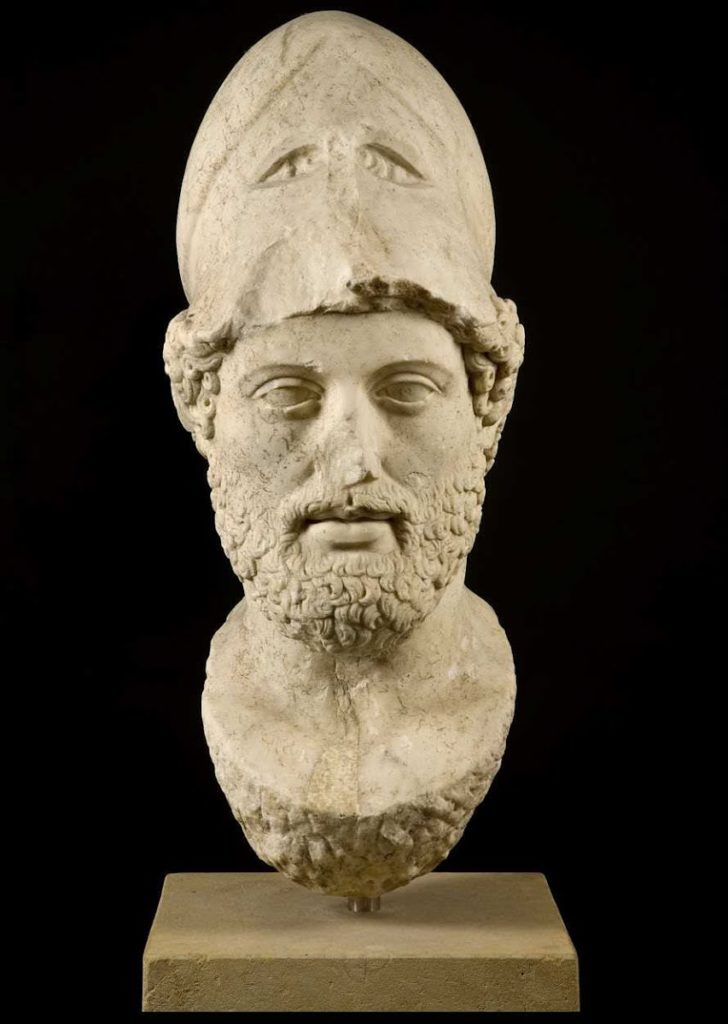

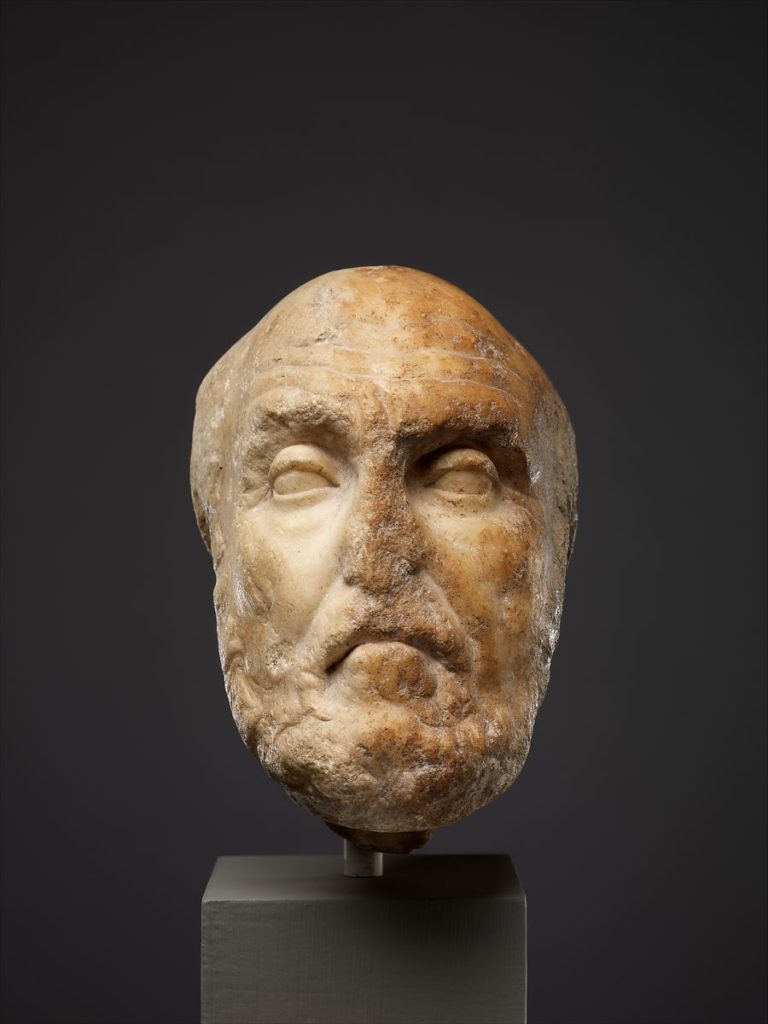

예술은 주기적으로 그 상징적 의미가 고갈되며 가치 절하의 시기를 겪는다. 그런 시기가 오면 예술은 스스로 재생되어야 한다는 선언을 하게 된다. 코난 도일은 신기에 가까운 통찰력을 지닌 천재였다. 그는 예술이 나폴레옹의 흉상 같은 싸구려 장식품이 되면서 그 상징성이 고갈되어 간다는 것을 감지한 것이다. 페리클레스와 아우구스투스의 상이 ‘장소의 정령 Genii Loci”으로서 성스러운 안식처에 놓이는 것으로 그 생애를 시작한 예술, 아니 그보다 더 이전, 테르미누스와 에르메스가 의례와 숭배가 이루어지는 신령스러운 장소를 지정하면서 시작된 예술이 말이다.*

홈즈는 물건으로 가득 찬 빅토리아 식 실내에서 존경하는 인물의 초상을 거는 상황에서, 뒤팽의 기법, 즉 생각의 연결 고리를 쫓다가 놀라운 관찰로 자신의 머리가 얼마나 비상한지 보여주며 생각의 흐름에 끼어드는 기법을 재연했다. 왓슨이 헨리 워드 비처Henry Ward Beecher의 초상을 어디에 걸까 고민할 때 홈즈는 그가 고든 장군General Gordon 초상 옆에 걸려고 한다는 것을 알아차렸다. 왓슨은 인본주의적 의사이자 빅토리아 시대의 진보주의자였고, 그의 안식처를 위한 가신들을 고르는 참이었다. 실마리를 날카롭게 볼 줄 알았던 발터 벤야민은 “실내[그러니까 가구를 들여놓은 실내]는 우주일 뿐 아니라 사적인 개인이라는 (범죄) 사건이다. 거주한다는 것은 흔적을 남긴다는 것이다.”라며 탐정소설이 19세기 실내의 산물이라고 지적했다. 벤야민은 포우가 인테리어 장식에 관심을 가진 사실과 그가 추리소설을 발명한 사실 간의 연관성을 본 것이다.

이제까지 우리가 살펴본 탐정들의 이름들이 산업혁명 때 분명히 그 맥이 끊긴, 고대 세계와 자연의 녹색 세계를 연결하려는 시도라는 사실을 눈치챈 적이 있는가? 그래서 현대 미술에서 이런 종류의 노력이, 즉 그리스 로마 문화와 유기적 세계의 융합이라는 시도가 지속적으로 이루어지고 있다. 최초의 탐정인 오귀스트 뒤팽이 그 공식을 정했다. 오귀스트라는 이름은 프랑스 혁명이 가져온, 이름의 새로운 트렌드를 보여준다. 즉 성인의 이름 대신 고대 인물의 이름을 선택해서, 훌륭한 황제의 이름을 연상시키는 Auguste 라는 이름에 뒤팽Dupin*, 소나무라는 뜻의 성이 더해진 것이다. 에르퀼 푸아로 Hercule Poirot의 경우도 영웅의 이름에 배나무를 더한 것으로 이 공식에 해당한다.* 쥘 메그레Jules Maigret 땅딸한 남자를 두고 이런 이름을 붙인 유머를 넘어서* maigre는 macer에서 이는 다시 mala, 사과라는 어원에서 온다. 셜록 홈즈는 “남자다움”을 뜻하는 색슨 인의 이름 + 오크 나무의 한 종류이다.* 다른 형태로 돌 + 도구를 뜻하는, 피터 윔지(Peter Wimsey, wimsey는 송곳gimlet이다)가 있고, 반복적인 페리 메이슨, 즉 “돌 + 석공”이 있다. 그리고 필명으로 존 르 카레가 있다. 그리고 존 에블린 톤다이크도 있다.

여기서 암시되는 것은 대중문화의 명민한 남자(이들에겐 머리와 뇌만이 중요하고, 몸은 우습고 연약한 것이라 매도한다)를 고대의 영웅적 정신과 나란히 놓는다는 것이다. 이 정신은, 예술이 말하기를, 우리 시대에 와서 지능으로 살아남는다. 운명으로서의 두상은 이렇게 새로운 의미를 띄게 된다. 고매한 타고남이나 곧고 청렴한 성품에 주어지는 고대의 자리가 아닌, 영특하고 지성적인 명철함이라는 의미다.

코난 도일은 이를 믿지 않았다. 부서진 두상이 곳곳에 나오는 것을 보면 알 수 있다. 포우 역시 이를 믿지 않았다. “어셔 가의 몰락”에서 두상은 탁자 위에 놓여있는 것이 아니라, 그 집 자체인 것이다. 집의 두 가지 의미, 즉 가족과 거주지라는 두 가지 의미가 합쳐지면, 이들은 서로 상충하거나, 지금 우리가 보건대는, 정신이 나누어진 상태, 즉 정신분열증적이라 할 수 있다. 이러한 이미지는 19세기 문학 전반을 통해 반복적으로 나타나는데, 호돈과 브론테, 그리고 멜빌에서 그러하다. 움베르토 에코가 <장미의 이름>을 썼을 때(보르헤스와 그의 난해함에 대한 비평적 접근으로서), 그는 코난 도일의 이야기를 가져다 쓰면서 그의 주인공(그러니까 중세의 셜록 홈즈)의 이름을 전형적인 노르만 영어 이름 윌리엄으로, 그리고 성은 저주 받은 집의 이름, 성이자 집까지 포함한 사유지의 이름이기도 한 베이스커빌로 했다.

탁자 위의 흉상은 그러고보면, 새로운 운명을 상징한다. 챨스 올슨이 라이너 마리아 게르하르트의 진부한 시작 스타일을 두고 “닳아버린 상징/ 마치 석고로 만들어진/ 포우의 머리에 얹어진 부분가발처럼”이라고 비판한 것은 (그는 이 때 아마도 찰스 이브스의 피아노 위에 있던, 예일대 야구모자를 쓰고 있던 바그너의 흉상을 떠올렸는지도 모른다) 인위적 스타일을 가면 또는 결함, 또는 상징이 지나치게 연장되어 소통의 힘을 잃어버린 상태에 비유한 것이다. (계속)

*리 헌트 Leigh Hunt(1784-1859)

영국의 비평가, 저널리스트, 에세이스트, 시인. 중요한 일간지의 편집장이었고, 키츠와 셸리의 친구였다.

*마리오 프라즈 Mario Praz(1896-1982)

이탈리아의 비평가이자 영문학자로, 18세기 19세기 유럽 문학을 연구했는데, 더불어 디자인 비평서로 알려졌다. 그의 책 The House of Life 와 An Illustrated history in Interior Design에서 인테리어의 역사와 이론을 다루며 사람들이 어떻게 실내에 거주하고 자신의 방식대로 실내를 꾸며가는지 보여주었다.

*릴케의 시 "고대 아폴로의 토르소"의 전문.

*키클라데스 제도의 청동기 시대 문명에서 온.

*조각은 과거에 건축 안에서 ‘장소성’을 위해, 즉 공간의 구체성을 주기 위해 놓여진 오브제였다.

*Dupin은 옛 프랑스어로 du pin 즉 from the pine( 라틴어로 pinus)에서 온 이름이다.

*Hercules 헤라클레스와 배 poire또는 배나무 poirier를 조합했다는 말.

*Maigre는 불어로 말랐다는 의미.

*Sherlock 은 shear lock, 즉 짧게 자른 머리라는 뜻이고, holm은 지중해에서 자라는 상록스 오크 나무인 holm oak의 줄임말이다.

Urban man has a folklore that has flourished with the energy and success of myth and fable, and has appropriated, perhaps through an organic, unconscious design, symbols native to the art of still life. The printed book began as its medium; the moving picture, radio, and television continue the process. By urban folklore I mean Don Quixote, Sherlock Holmes, Tarzan of the Apes: figures whose diffusion from their texts was instantaneous, other authors taking them up, so that their locale as characters is the public imagination, the text being only a source or classical reference point for their reality.

Sherlock Holmes’s rooms at 221B Baker Street are known to us all. There is a table with chemical apparatus. There is a violin, a multiple-volumed scrapbook of newspaper clippings about crimes. There is a Persian slipper jackknifed to the mantelpiece in which Holmes keeps his tobacco. This room began as Roderick Usher’s, in Poe’s tale “The Fall of the House of Usher,” and as Auguste Dupin’s room in Paris, in Poe’s tales of that proto-Holmesian detective. In a deeper sense, this room began as Leigh Hunt’s, where Keats wrote “Sleep and Poetry.” It is the philosopher’s lair, the poet’s, the den of the man of feeling and sensitivity. In Mario Praz’s study of interiors—a study that descends from Poe’s seminal essay on the philosophy of furniture—we can see many such rooms: the studies of Goethe, Alexander von Humboldt, Cuvier, of scientists and poets, dilettantes, collectors, amateurs of all sorts.

In Holmes’s room at one time there was a bust of the detective, sculpted by one Oscar Meunier. It is, we recall, a decoy for a deadly silent air rifle. It is a means for Holmes to be in two places at once. But it also completes an inventory of items on a tabletop requisite for a kind of still life.

This paradigmatic still life is of books and the implements of philosophical contemplation: a pipe, a musical instrument—a violin in Holmes’s case, a guitar in Roderick Usher’s, a flute in Thoreau’s (whose tabletop at Walden Pond was a copy of the Iliad in Greek, a rock, a leaf, and the flute) —a wine glass and bottle (coffee or teapot with Holmes, wine being for his dinners to celebrate the triumph of a case), and a classical bust.

In these things we recognize the schema of a typical cubist still life by Picasso and Braque, as well as a blueprint for still life as it is accepted in our time. It is possible to trace this tabletop back to St. Jerome’s study, with books and lion, of medieval tradition.

But let us return to Holmes’s bust. The Oscar Meunier who made it may well be a real person, like Holmes’s ancestor the French painter Horace Vernet. The likelihood, however, is that Conan Doyle invented the name, taking Meunier from a contemporary Belgian sculptor, Constantine Meunier, who did busts, and from his acquaintance and fellow novelist Oscar Wilde, who wrote in The Picture of Dorian Gray a book about a work of art that suffered the fate from which its sitter was, for a time, magically excused, just as Holmes’s bust died in his stead.

The smashing of busts had happened before in Holmes stories, and a figure at a window meant to deceive had been used in "The Case of the Copper Beeches". In "The Adventure of the Six Napoleons", we have the systematic smashing of a mass-produced bust of the emperor. The villain is only trying to recover a black pearl of the Borgias hastily embedded in the wet plaster of one of the busts when it was on the assembly line, but for us the symbol remains as a detail of the iconography of still life being canceled by violence, and we want to know why. “A plaster bust of Napoleon, which stood with several other works of art upon the counter, lying shivered into fragments,” runs the text. That “shivered into fragments” is interesting: classical art had for a century been appearing in fragments in museums and collections. Fragmentation was the very condition of the past. A debate maintained as to whether the fragments should be put back together with wax, as the Romans did, and as the eighteenth century had taken up.

Or was there some poignant eloquence in leaving the fragments in their ruin? From Winckelmann, who was writing a study of the torso of an athlete when he was murdered in 1768, to Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo” we can trace a preference for the broken statue (as Ezra Pound in his “Papyrus” was to insist on the meaningfulness of incomplete classical texts as against their restoration).

Rilke’s poem is one way of accepting this broken statue:

Although we never knew his lyric head

from which the eyes looked out so piercing clear,

his torso glows still like a chandelier

in which his gaze, only turned down, not dead,

persists and burns. If not, how could the surge

of the breast blind you, or in the gentle turning

of the thighs a smile keep passing and returning

towards the center where the seeds converge?

If not, this stone would stand all uncompact

beneath the shoulders’ shining cataract,

and would not glisten with that wild beast grace,

and would not burst from every rift as rife

as sky with stars: for here there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

Another way of seeing this archaic Greek torso is Constantin Brancusi’s Torso d’un jeune homme—which is a highly polished section of tree trunk to which Brancusi has fitted two more, much shorter, sections of the same trunk, as divaricate legs from hip bone to crotch to form a chastely sexless and radiantly pure torso of a boy. Brancusi returned the idea of torso back to its most archaic, as in African carving, where the whole figure is always found in the available volume of tree trunk, referring as well to Cycladic sculpture with its minimalization of form and undetailed gracefulness.

It is indeed odd to find the greatest of modernist sculptors completing the work of an Italian hack artisan in a Sherlock Holmes story, but that is what’s happening. We can always trust Conan Doyle, as we can trust Poe. Doyle’s sense that sculpture had gone into a terminal etiolation was an accurate one. “This Dr. Barnicot,” we read, “is an enthusiastic admirer of Napoleon, and his house is full of books, pictures and relics of the French Emperor.” And: “the famous head of Napoleon by the French sculptor Devine, one in his hall in the house on Kensington Road, and the other on the mantlepiece of the surgery at Lower Brixton.” The smasher of these busts, when killed, was found to have in his pockets “an apple, some string, a shilling map of London, and a photograph.

Art periodically runs a course into degradation, its symbols exhausted. At such moments art itself announces its need to be renewed. Doyle was a genius of almost preternatural perspicacity. He could feel exhaustion in the symbolic content of an art when all its materials had become bric-a-brac, like the bust of Napoleon, an art that began its life as Pericles and Augustus as gentii loci on a sacred hearth, or even before that as Terminus and Hermes defining numinous space for the purposes of rite and worship.

The honorific placing of images in the clutter of a Victorian room is the occasion for Holmes’s replaying Dupin’s trick of following a line of thought and interrupting it with an observation proving his acuity. Holmes breaks in on Watson’s thought when he is trying to decide where to hang a portrait of Henry Ward Beecher, which proves to be beside a framed portrait of General Gordon. Watson, humanitarian physician and Victorian liberal, is choosing lares and penates for his hearth. Walter Benjamin, that astute reader of clues, says that “The interior. [that is, the furnishings of a room] is not only the universe, but the case of the private individual. To inhabit means to leave traces.” He notes that the detective story is born in the nineteenth-century room, seeing the connections between Poe’s attention to interior decoration and his invention of the tale of ratiocination.

Has it been noticed that in the names of detectives we can see an attempt to elide the classical world, so patently lost in the industrial revolution, with the green world of nature, and thus affect the fusion that modern art has expressed in so many ways, a coalition of Graeco-roman culture and the organic? Auguste Dupin, first of detectives, sets the formula. The Auguste reflects the new system of first names inaugurated by the French revolution, shelving saints’ names for classical, but it also alludes to an exemplary emperor, coupling it with the pine tree, Dupin. The formula holds in Hercule Poirot, combining hero and pear tree, in Jules Maigret, where beyond the joke of a stout man being named Maigret lies the deeper maigre from macer from mala, apple. In Sherlock Holmes we have a Saxon name meaning “manly” + a kind of oak. An alternate form is “stone + implement,” Peter Wimsey (a wimsey is a gimlet); and the reduplicative Perry Mason, “stone + stone-cutter.” And there’s the pseudonym John Le Carré. And John Evelyn Thorndyke.

What’s at play here is the aligning of the perspicacious man of popular culture (one who descries, and is all head and brain, the body being comic and weak) with the archaic heroic spirit. This spirit, says art, survives in our time as intelligence. The head as fate takes on new meaning, not as the ancient seat of a noble nature and a stoic rectitude of behavior, but as cunning and intellectual sharpness.

Conan Doyle was not convinced of this: hence all his messages of crushed heads. Poe was not convinced of it either, for the head in “The Fall of the House of Usher” is not on the tabletop but is the house itself. The two meanings of house, family and dwelling, combine: and they are at odds or, as we can say now, schizophrenic, of divided mind. This image recurs throughout nineteenth-century literature, in Hawthorne, in the Brontés, and in Melville. When Umberto Eco wrote The Name of the Rose, sustaining a critique of Borges and his enigmas, he cast the story as a plot by Conan Doyle and chose for his protagonist (who is a medieval Sherlock Holmes) a typical Norman English name, William, and the name of a house under a curse that is both the family name and that of the estate, Baskerville.

The bust on the tabletop, then, is an emblem of a new fate. When Charles Olson disapproved of the derivative poetic style of Rainer Maria Gerhardt “as signs worn / like a toupee on the head of Poe cast / in plaster” (and he was perhaps thinking, when he said this, of Charles Ives’s piano with its bust of Wagner wearing his Yale baseball cap), he was making a symbol of the artificial as a mask or defect, or a prolongation of symbol beyond its power to communicate. (to be continued)

c 480-470 BC. The Louvre, Paris

RELATED POSTS