The Head as Fate

부서진 두상: 재생의 선언

02

Text by 가이 다벤포트 Guy Davenport

Translation by 박상미 Mimi Park

예를 들어보자. 언제인지도 모르는 오래 전, 버드나무 정령인 오르페우스의 --그의 노래로 동물을 길들이고 심지어 물질마저 관통하여 돌이나 나무를 움직일 수 있었던—아내 에우리디케(또는 아그리오페)는 뱀에 물려 세상을 떠난다. 오르페우스는 그녀의 영혼을 따라서, 자신의 음악의 마법을 이용하여 죽은 자의 세계까지 내려가서 하데스를 매료시키고 그녀를 되찾는다. 하데스는 조건을 건다. 이승에 올라갈 때까지 에우리디케가 따라오는지 뒤를 돌아봐서는 안된다는. 지하세계를 나오자마자 오르페우스는 뒤를 돌아봤는데, 에우리디케는 아직 지하세계를 벗어나지 못한 상태였다. 그 이후로 오르페우스는 여자 대신 소년들을 사랑하였는데, 트라키아의 마이나스들(광란하는 여자)에게 몸이 찢겨 죽는다. 잘려진 그의 머리는, 노래하며, 헤브로스 강을 떠내려가 레스보스 섬에 도착한다. 그의 머리는 그곳 사원에 걸렸고, 사원은 그의 신탁을 받는 곳이 되었다.

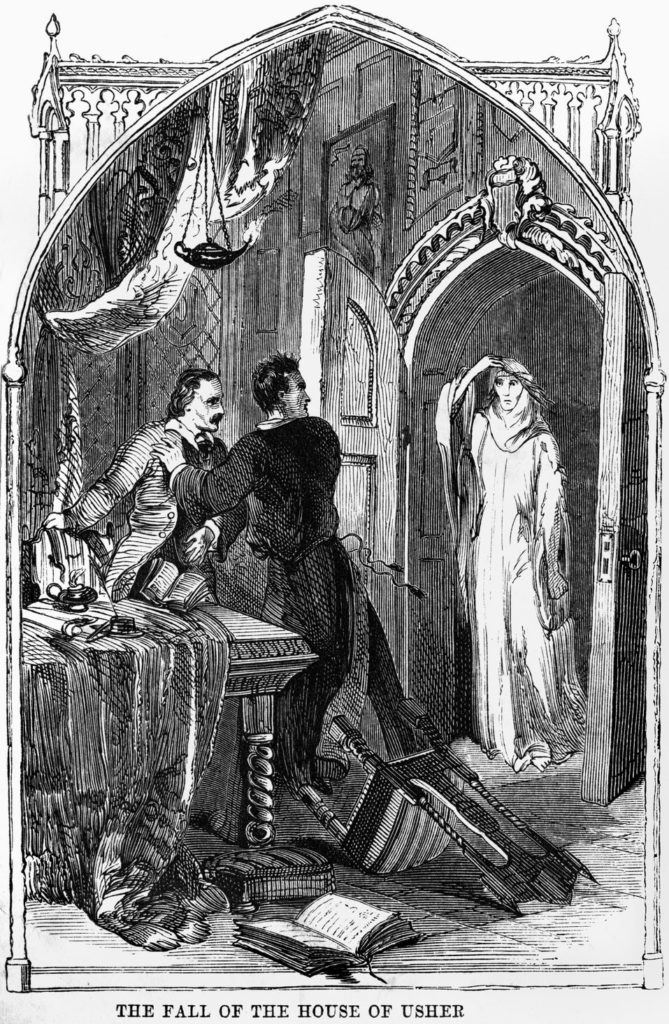

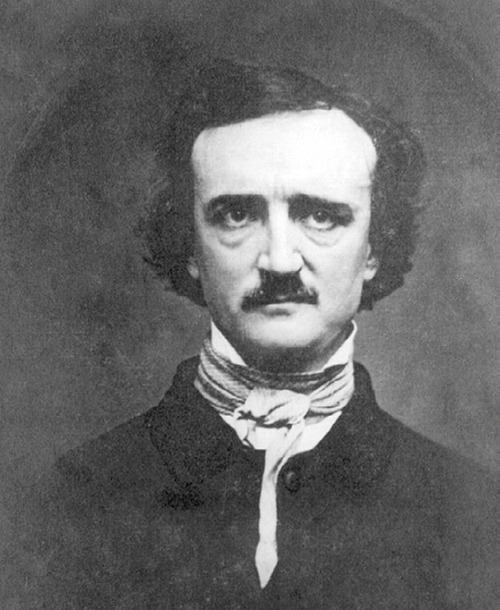

포우는 이 신화를 고딕 모드로 바꾸며, <어셔 가의 몰락>으로 재구성한다. 그 과정에서 포우는 그의 이슬람 천사, 이스라펠 –“그의 심장 줄은 류트였다”*- 의 신화를 완성하기 위해 쌍둥이 상징을 구성한다. 오르페우스의 리라와 이스라펠의 류트는 포우와 함께 서양 시단에 재입장하는데, 그 사이에는 슈펭글러가 파우스트와 마고스 문화의 충돌이라 부를만한 긴장감이 있다. 오르페우스 신화의 의미는 포우에 의해 걸러졌는데, 반전된 오르페우스-어셔, 그리고 그의 천사 이스라펠에 대한 포우의 관심은 아름다움의 순간성, 그리고 이를 불멸의 상징으로 바꿀 수 있는 예술의 힘에 있었다.

포우의 세 가지 모드, 또는 이와 밀접한 연상 관계를 갖는 상징들의 조합은 그의 작품 속에서 음악의 조성처럼 작용한다. 이런 조화를 만들어내기 위해 그는 각 스타일에 걸맞는 제목과 형용사, 그리고 일련의 특징적인 이미지들을 만들어낸다. 그는 이들에 아라베스크, 고딕, 그리고 고전이라는 이름을 부여한다. 그에게 아라베스크란 이슬람의 문화 코드, 즉 꼬불꼬불한 글씨체나 카페트의 복잡하게 꼬인 무늬, 시각적 이미지보다 음악적, 언어적인 표현을 더 선호하는 경향, 천문학과 수학에 나타나는 추상성 등을 의미했다. 어떤 면에서 포우에게 아라베스크는 유대교에 대한 정서적인 유대감 의미하기도 했는데, 그는 종교적으로 중립적이었기에 이는 그에게 불편한 부분이기도 했다. 포우에게 아라베스크는, 그의 초기 시 “이스라펠”(그가 여기서 어떻게 “이스라엘”을 감추고 또 드러내는가에 주목하자) 을 보아도 알 수 있듯 강렬한 영성을 뜻했고, 또한 지성을 겸비한 개인적 아름다움을 뜻했다. 그에게 있어 혼이 담긴, 운명의 여성이란 아인스타인의 뇌를 가진 바바라 스트라이젠드 같은 존재인 듯하다.

포우는 아라베스크에, 감성, 감각(능력에 해당하는), 사변적 사고, 관능, 그리고 정교함이라는 의미들을 부여했다. 이는 아라비아의 영원한 태양이고, 칼리프가 다스리는 비잔티움의 수학적인 별빛이다.

포우에게 고딕이란 “영혼의 독일”을 뜻했다. 신경쇠약, 우울, 미신과 초자연적인 성향으로 비극적으로 운명지워진 이성, 파우스투스의 고집과 자만심, 햄릿의 격동적 영혼, “울랄룸,” “도래까마귀(더 레이븐),” “어셔 가의 몰락”의 음산한 가을 날씨를 뜻했다. 우리는 역사적으로 고딕 모드를 포우의 가장 특징적인 경향이라고, 어쩌면 잘못 생각해왔다. 특히 유럽에서는 이 경향에 집중하여 포우를 연구해왔는데, 말하자면 이런 측면이 대중에게 알려진 것일 뿐이다.

포우에게 고전classic이란, “그리스의 영광과 로마의 웅장함,”바이런, 셸리, 키이츠로 대변되는 헬레니즘적 클리셰, 이 모든 것이 거의 모두 담겨있는 고전적 흉상, 코린트 기둥, 호메로스, 아나크레온, 사포에 대한 모호한 생각들, 동전에 새겨진 알렉산더의 옆모습, 서구 사상의 기반이 된 플라톤의 이데아론과 아리스토텔레스의 보편적 관심 등이 그것이다.

그러니까 아라베스크는 이국적이었고, 고딕은 불길했고, 고전은 고상했다. 포우의 이러한 상징적 코드는 슈펭글러가 문화를 마고스 적, 파우스트 적, 아폴로 적 문화로 분류한 것과 일치한다. 이를 보면, 슈펭글러가 포우를 읽었을 가능성도 있다. 보들레르, 말라르메, 발레리가 미국인들보다 더 강렬한 상상의 나래를 펼치며 포우를 읽었듯이 말이다. 또는 페르낭 브로델이 그의 지중해 연구에서 요구했던, 쓰이지 않은 상상의 지리학에서 우리는 중앙해(The Middle Sea)—바르셀로나에서 에베소* (에베소는 로마 제국 이오니아 주의 수도로, 지금의 터키 서부해안(카이스테르 강 하구)에 있던 항구 도시이다. 당시 상업 및 교통의 중심지였고 인구 50만이 살던 대도시로, 세계 7대 유물에 속하는 아데미의 신전과 극장이 있었지만 신약 시대에 접어들며 쇠퇴하였다. ) 에 이르는, 이탈리아, 크레타 섬, 사르디니아, 시실리를 포함하는 프랙탈 연안--의 북쪽 연안이 시적인 배열을 이루며 포우의 고대와 슈펭글러의 아폴로적 문화를 구성하고, 이스탄불에서 탄지에에 이르는 남쪽 연안(모여있는 섬에서 터키의 동쪽, 페르시아, 아라비아에 이르는)은 포우의 아라베스크와 슈펭글러의 마고스적 문화를 이루고 있다는 것을 발견하게 될 것이다. 양쪽 지역 모두 넉넉하게 겹치는 측면이 있고, 워싱턴 어빙* 덕에 포우에게 알람브라 궁전은 본질적으로 스페인이고, 터키의 지배 하에 있던 아테네도 그에겐 본질적으로 그리스였다. 포우의 고딕 영역은 슈펭글러의 파우스트적 문화처럼 북부 유럽(포우에게 이곳은 대혼란의 지대였고, 슈펭글러에겐 전망이 없는 러시아의 초원이었다)이 아니라 로마 제국의 북쪽 경계 지역이라고 할 수 있다. 포우의 선조가 북미로 이주하기 전, 포우에게 물려주게 된 유산도 여기서 대부분 형성되었다.

**

깊은 숲 속 어딘가, 베니스에서 책들, 스페인에서 기타, 네덜란드에서 유화 물감이 길을 통해 운반되어 온 곳, 그곳에 어셔 가의 집이 있다.

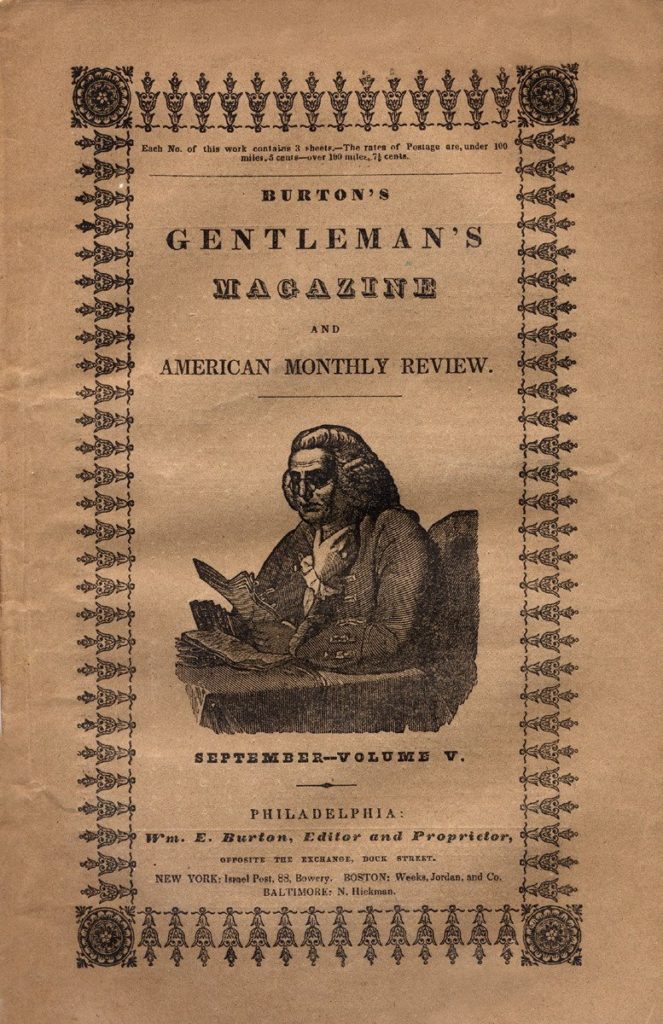

포우(1809-1849)는 어느 작가보다도 신세계로 유입되는 중요한 정보를 잘 알아보는 사람이었다. 40년 간 그의 삶은 링컨(1809-1865)과 다윈(1809-1882)의 40세까지의 삶과 그 시기가 일치한다. 베토벤의 5번 교향곡과 베르디의 맥베스 사이에서, 나폴레옹의 스페인과 이탈리아의 종교 재판 폐지에서에서 주세페 마치니(1805-1872)가 세운 로마 공화국까지의 시기이다. 격동의 시기였지만 이 시기는 우리에게 시와 잡지에 실리는 과학 기사에 풍성한 내용을 제공한 꿈 같은 시기였다. 전해들은 말, 소문, 맹렬한 추측에 의존했던 창조적인 사람에게도 마찬가지였다.

“어셔 가의 몰락”의 주된 정서는 고딕이다. 독일의 낭만주의를 스콧, 콜리지, 매튜 그레고리 루이스가 영국화시키고 변형시킨 스타일에 가깝다고 할 수 있다. 하지만 이는 또한 오르페우스와 에우리디케 신화를 바탕으로하며, 아라베스크의 과민증과 환상곡이 전체 작품에 울려퍼지며 흥미로운 대조를 이룬다.

어셔라는 이름은 고 프랑스어로 문지기 ussier, 또는 버드나무라는 뜻의 osier 에서 온 것이다. 두 가지 중 어디서 온 것이든 상관 없을 것이다. 오르페우스는 버드나무라는 뜻인데다가, 그리고 그의 운명은 그가 열 수는 있었으나 다시 들어갈 수는 없는 문에 달려있었으니. 그의 하프는 비문에 쓰인 것처럼, 그의 머리와 함께 아폴로 신전에 걸렸고, 그는 음악을 통해 돌과 나무의 감응을 얻었을 뿐 아니라 죽은 자의 세계에서 사랑하는 사람을 되찾기도 했다.

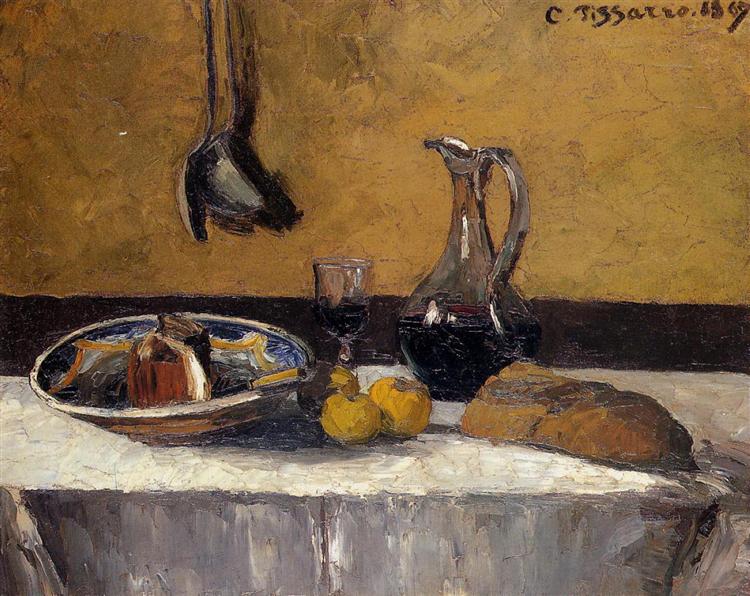

적막한 이야기의 한 가운데, 독일의 음산한 바람과 썩어가는 이끼와 불안한 돌들, 그리고 지하의 하데스를 모두 넘어, 포우는 탁자를 놓았다. 정물이 있는.

사적인 공간 속에 놓여진 탁자, 잠시 연주를 쉬고 옆으로 밀어 둔 악기 하나, 악보, 신문, 파이프, 과일이 담긴 그릇, 흉상(대체로 고전적인 형태의) 등이 지난 5백 년간 전형적인 정물을 이루어온 오브제들이다. 악기는 대대로 다양한 종류의 친밀함(관련성)을 자아낸다. 가장 고대의 악기라면 오르페우스의 리라일 것이다. 흉상이 원형적으로는, 드라마의 근원에 있던, 디오니소스의 가면인 것처럼 말이다. 이 둘은 함께 배우가 되고 음악이 되어 죽은 자를 무대 위로 불러내어 말하게 한다. 르네상스 시기에 오면 악기는 오감의 즐거움을 상징하는 오브제 중 하나가 된다.

정물은 사람이 읽고, 먹고, 와인을 마시고, 음악을 연주하고, 대화하는 문명화된 집 안에 어떤 공간이 있다는 것을 상정한다. 이는 고대의 식당, 즉 집안에서 사람들을 대접하고 즐기는 공간(플라톤의 심포지움, 그리스도가 제자들과 있었던 2층 방, 보에티카에 있는 플루타르크의 편안한 집)에서 (학자나 성자가 책과 함께, 그리고 사자와 함께 있던) 중세의 서재까지 끊이지 않고 이어져온 전통이다.

포우는 어셔 가의 서재 탁자 위에 그가 아는 정물의 전통에 대한 지식을 총동원해서 많은 책들과 악기들로 탁자 위 정물을 배열했다. 수르바란의 그림처럼 정물의 배경은 어둡고, 사물 위에는 렘브란트 같은 빛이 반짝인다. 이 방에도 커튼과 골동 가구가 있고, 퓨즐리 풍으로 그린 그림들이 걸려있지만 이들은 카날레토나 터너처럼 밖으로 열린 풍경이 아닌, 폐소 공포증을 불러일으키는 적막함을 더한다.

이 책들은 “오랫동안 이 병자의 정신 세계를 유지하는데 적지 않은 공헌을 해준” 책들이었고, 화자가 이 집을 방문했을 때 대화의 소재가 되었고, 매력적이고 신비로운, 어셔의 보기 드문 지성과 어두운 상상력을 암시하기 위한 것으로, 이야기 속에서 하나의 목록으로 제시된다. 책들은 다음과 같다. (계속)

*포우는 그의 시“이스라펠" 에“그리고 천사 이스라펠, 그의 심장 줄은 류트였고, 모든 신의 창조물 중 가장 달콤한 목소리는 가졌다”라는 코란의 문장을 인용하였다.

*워싱턴 어빙 Washington Irving (1783 –1859)

미국의 단편 소설가, 산문가, 전기 작가, 외교관. 그라나다에 머물며 알람브라 궁에 관련한 이야기와 전설 등을 채집하고 기록하여 <알람브라 이야기>를 썼다. 이 책은 서구 세계에 알람브라를 알리는 데 큰 공헌을 한다.

An example. Back before the measure of time in Olympiads, the willow tree spirit, Orpheus, whose singing could tame animals and could even penetrate into matter and move rocks and trees, lost his wife Eurydice (or Agriope) to the bite of a serpent. He followed her soul to the realm of the dead, opening his way there with the magic of his music, and charmed Hades into returning her to him. Hades made the stipulation that Orpheus should not look back to see if Eurydice was following. He looked back as soon as he was out of the underworld, but Eurydice was not. He thereafter loved boys rather than women, for which he was torn asunder by Thracian Maenads. His head, singing, floated down the Hebros River, to the island of Lesbos, where it was hung in a temple, and became one of the oracles.

Poe recasts this myth as “The Fall of the House of Usher,” transposing it to his gothic mode. In doing so he constructed a twin set of symbols to complement his own myth of an Islamic angel, Israfel, “whose heart-strings are a lute.” Orpheus’s lyre and Israfel’s lute re-enter Western poetry with Poe in a tension of what Spengler would call Faustian and Magian cultural styles. The myth of Orpheus itself was drained of significance for Poe, whose concern with his inverted Orpheus-Usher and his angel Israfel was the transience of beauty and the ability of art to fix that transience in an immortal sign.

Three stylistic modes, or associative kinships of symbols, function like musical keys in all Poe’s work. To this organizing harmony he draws attention in titles, adjectives, and characteristic sets of images proper to each mode, to which he assigned the names arabesque, gothic, and classical. By arabesque he meant the cultural idiom of Islam, its curvilinear calligraphy and intertwined convolutions in the design of its carpets, its predilection for the musical and verbal over the pictorial, its abstract spirit expressed in astronomy and mathematics. In some sense, what Poe called arabesque is his emotional analogue. for Judaism, which his religious neutrality found uncomfortable. The arabesque is Poe’s idiom for an intense spirituality, as in his early poem “Israfel” (but note how that word both conceals and shows Israel), and for personal beauty combined with intellect, as in his soulful and fated women who seem to be Barbra Streisand with Einstein’s brains.

To the arabesque Poe assigns an accomplished sensibility, acumen, speculative thought, sensuality, and cunning. It is the eternal sun of Arabia and the mathematical starlight of Byzantium under the Caliphate.

By gothic, he meant “the Germany of the soul,” neurasthenia, melancholia, a rationality tragically disposed toward superstition and the supernatural (while intelligently exploring the archaic feeling that all matter is alive and perhaps sentient), the willfulness and hubris of Faustus, the turbulent soul of Hamlet, the bleak autumnal weather of “Ulalume,” “The Raven,” and “The Fall of the House of Usher.” It is the mode we have traditionally, if wrongly, assumed to be Poe’s dominant one, the one that Europe focused on in its connoisseurship of Poe: the one that has, so to speak, gone public.

By classical, Poe meant “the glory that was Greece and the grandeur that was Rome,” the received Hellenistic cliché in all its Byronic, Shelleyan, and Keatsian masks, almost wholly expressed in the classical bust, the Corinthian column, a vague notion of Homer, Anacreon, and Sappho, Alexander’s profile on a coin, Plato’s ideality and Aristotle’s universal attention as the bedrock of Western thought.

The arabesque, then, is exotic, the gothic sinister, the classical noble. That these symbolic idioms correspond to Spengler’s division of cultures into Magian, Faustian, and Apollonian may mean that Spengler read Poe, like Baudelaire, Mallarmé, and Valéry, with a greater imaginative intensity than Americans have ever read Poe. Or it may mean that in the unwritten geography of the imagination Fernand Braudel asks for in his study of the Mediterranean we will discover that the northern shore of the Middle Sea—from Barcelona to Ephesus along a fractal coast that laces in Italy, Crete, Sardinia, and Sicily—is of a piece in its poetic configuration of the world, and constitutes Poe’s classical and Spengler’s Apollonian culture; and that the southern coast from Istanbul to Tangier, with a gathering inland to the east of Turkey, Persia, and Arabia, is Poe’s arabesque and Spengler’s Magian. There are rich confusions at both ends, so that the Alhambra, thanks to Washington Irving, was quintessentially Spain for Poe, as Athens in a Turkish zamindari was his quintessential Greece. Poe’s gothic realm, like Spengler’s Faustian, is not northern Europe (which for Poe was the land of maelstroms and for Spengler the perspectiveless steppes of Russia) but the upper boundary of the Roman Empire, where Poe’s own heritage was shaped for transfer to North America.

Somewhere in a deep forest, reached by roads bringing books from Venice, a guitar from Spain, oil paints from the Netherlands, sits the House of Usher.

Poe more than any other writer was keenly awake to the thin lines of vital communication flowing into the new world. His forty years of life are coterminous with Lincoln’s and Darwin’s first forty years, between Beethoven’s Fifth and Verdi’s Macbeth, from Napoleon’s abolition of the Inquisition in Spain and Italy to the Roman republic under Mazzni, and yet those years seem to us to have been spent in a kind of dream tKat fed on poetry and popular articles on science in magazines—a creative mind 2 that worked with hearsay, rumor, and fierce speculation.

“The Fall of the House of Usher” is in its dominant mode gothic: German Romanticism as anglicized and transformed by Scott, Coleridge, and Matthew Gregory Lewis. But it is written over and in counterpoint to the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, with an arabesque hypersensitivity and fantasia playing over the whole.

The name Usher derives from either the Old French ussier, a doorkeeper, or osier, a willow tree. Either way a link connects it with Orpheus, whose name means willow, and whose fate was in doors he could open but not re-enter; whose harp, like the one on the epigraph, temple of Apollo; who could was suspended, along with his head, in a sentience in stones and trees with music, and who brought a reach the beloved back from the dead.

In the still center of the story, beyond the periphery of German winds, rotting lichen, insecure stone, and metallic Hades below, Poe has placed a tabletop, with objects.

A tabletop in its own intimate space, a musical instrument that has been put aside for a moment, a book or sheet of music, a newspaper, a pipe, a bowl of fruit, a bust, usually classical: such is the traditional still life for the past five hundred years. The musical instrument displays versatile affinities from age to age. Most archaically it is Orpheus’s lyre, as the bust is archetypally a mask of Dionysus at the origin of drama. The two together are actor and music summoning, the dead to speak for a while on stage. By the Renaissance, the musical instrument had joined objects emblematic of the pleasures of the five senses.

Still life, positing that there is a space in a civilized house where one reads, eats, sips wine, plays music, converses, is in an unbroken tradition from the classical dinner floor that was the household’s place for conviviality (Plato’s Symposium, Christ with his disciples in the upper room, Plutarch’s comfortable house in Boeotia) through the medieval studium (scholar or saint among his books, with lion).

Poe arranged the still life of “many books and musical instruments” on Usher’s library table with a full sense of the tradition of still life available to him. As in a Zurbardn, the surrounding space is a darkness in which objects gleam with a Rembrandtesque light. We can make out in this room draperies, antique furniture, and paintings in the manner of Fuseli that do not open the room out with vistas like a Canaletto or Turner, but turn it back on its claustrophobic airlessness.

The books, “which, for years, had formed no small portion of the mental existence of the invalid,” and which have been topics of discussion during the narrator’s visit, are listed in a catalogue that is meant to be enchanting, mystifying, and suggestive of Usher’s rare intellect and dark imagination. These books are: (To be continued)

Orpheus and Eurydice, ca. 1500-1506

RELATED POSTS