The World of Mahk

Interview with 조병수 Byoungsoo Cho

by 박선영 Sunyoung Park

“막은 장식을 위한 장식을 포함하여, 실질적임과 진솔함을 가로막는 모든 것에 대한 단호한 거절의 제스처이다.”

“Mahk is an unapologetic rejection of refinement for the sake of refinement, of ostentation that gets in the way of practicality or honesty.

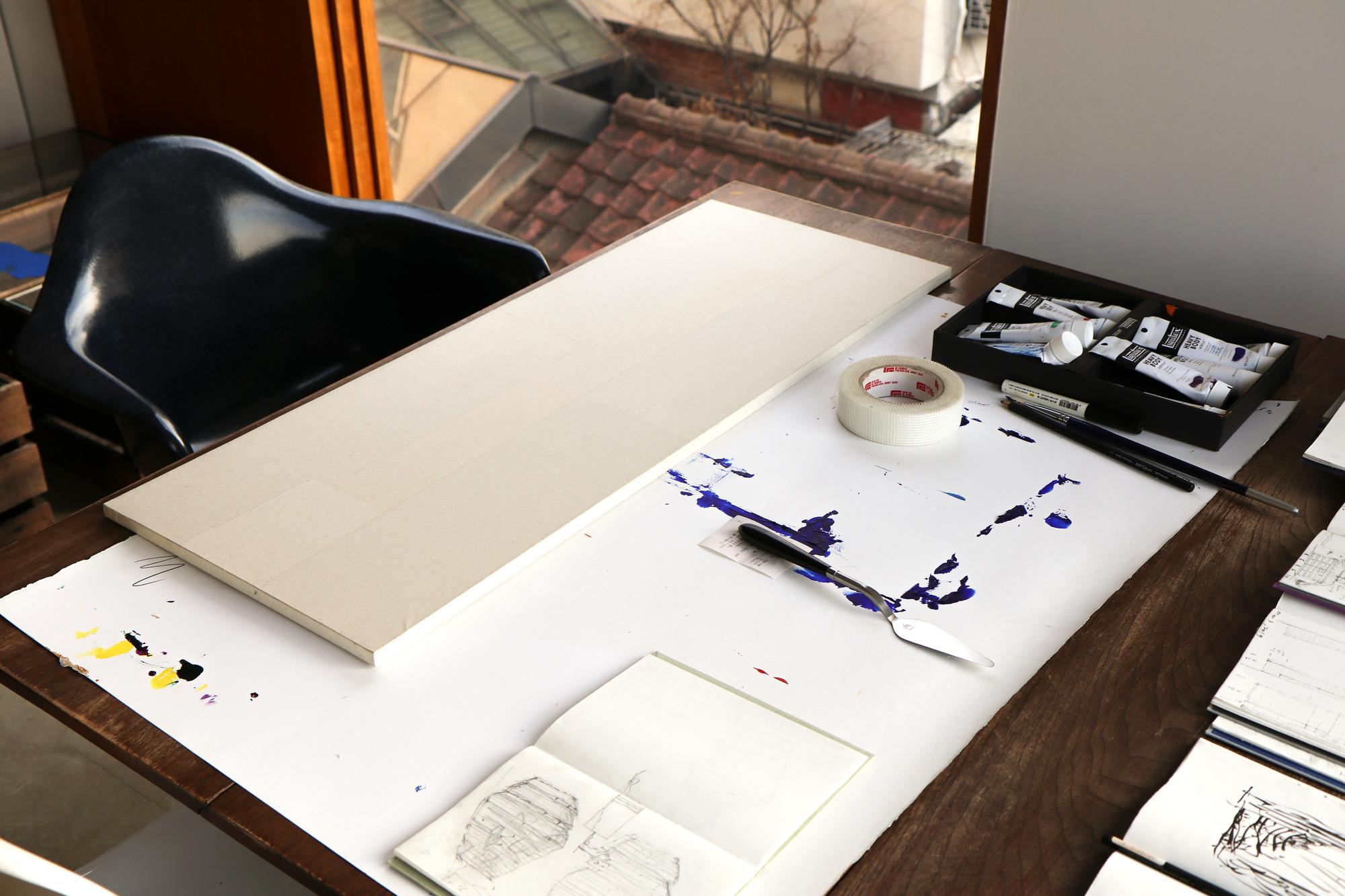

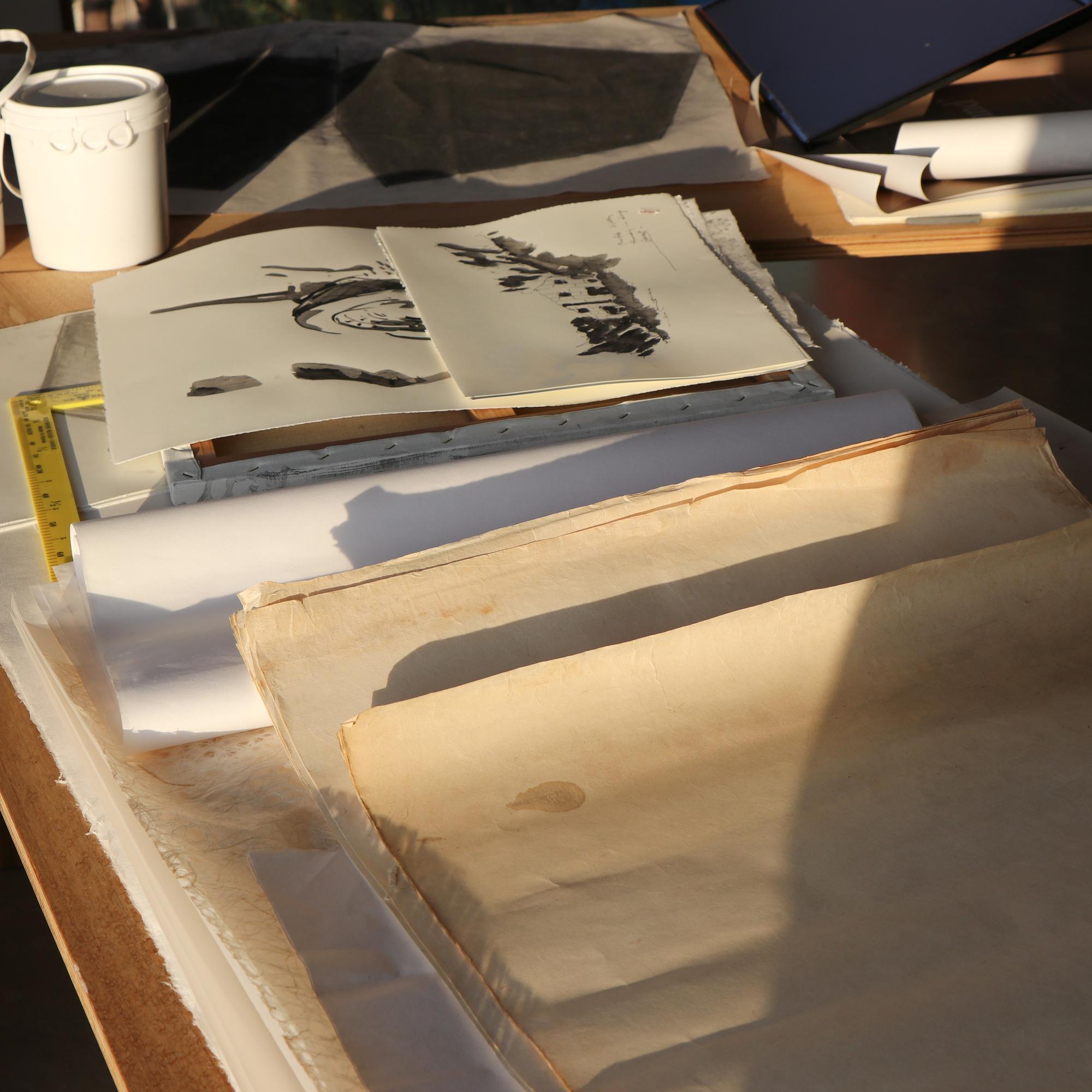

건축가 조병수를 생각하면, 그의 건축보다 먼저 떠올려지는 것이 있다. 그의 스튜디오 한 층을 가득 차지하고 있는 고재 덩어리와 단면이 잘린 돌들. 목탄이나 붓으로 그려진 드로잉들이 이곳저곳 널려있는 풍경.

물성에 대한 탐구와 창의적 욕구를 드러내는 조병수의 스튜디오 작업은 내게 늘 강한 인상을 주었지만 그렇다고 의외는 아니었다. 예술 창작과 건축 디자인을 자연스레 넘나드는 면모는 결국 그의 건축 세계를 맞닿아 있는 게 아닌가. 이 두 작업 사이에서 일어나는 화학 반응이 건축가 조병수를 더욱 탄탄하게 만들었을 거란 생각이 들었다.

땅속으로 들어가 앉은 ‘땅 집’이나 경사면에 박힌 ‘ㅁ자 집’, 지평선 속으로 나직이 숨어 들어가는 ‘지평집’ 같은 조병수의 건축을 볼 때마다 ‘불완전함, 파격, 비어있음, 담백함, 모자람, 자연스러움’과 같은 말들이 떠올랐다. 어쩌면 건축가가 되기 이전에도 조병수의 내면에서는 우리의 아름다움과 그 본질에 대한 사색이 이어져 왔을 것이라고 짐작되었다.

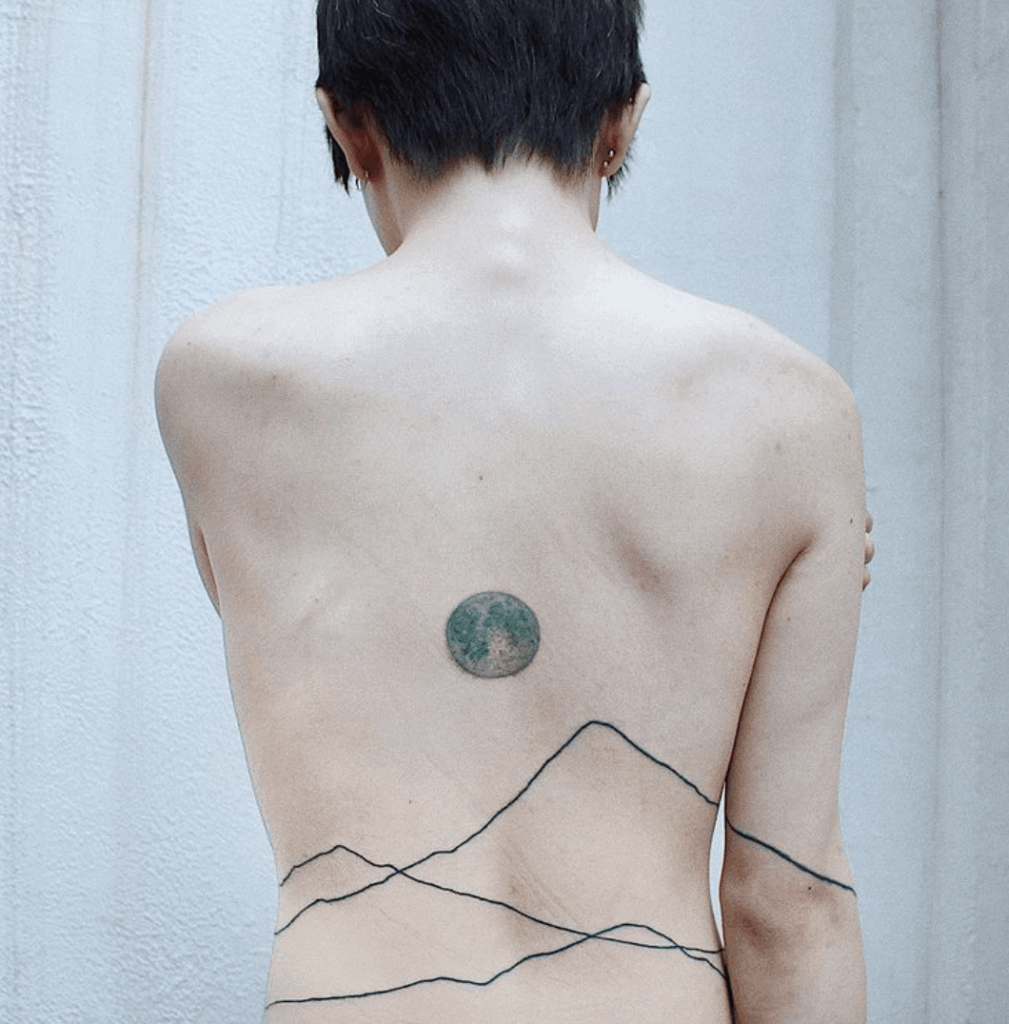

조병수는 한국적 미의 특질을 ‘막의 미학’에서 본다. 한국 전통 건축에서 보이는 배치의 우연성. 도공의 손 떨림에서 파생된 막사발의 불완전성. 승무에서 느껴지는 태연한 자태. 자연스러움(spontaneity)이나 진솔함(directness)과 같은 특성, 뚜렷한 양식보다 정서적 공명을 일으키는 우리의 미학적 특질을 ‘막’이라는 한 음절의 단어로 축약할 수 있다고 그는 말한다.

한국적 세계관은 즉흥성이 발휘될 수 있는 공간을 의도적으로 남겨두는 것이 특징적이라 할 수 있는데, 나는 이 정신이 한국어에서 접두어로 쓰이는 “막Mahk”이라는 단어에서 잘 드러난다고 생각한다. “막”의 정신은 한국의 전통 음식, 음악, 글, 춤 등 모든 분야의 한국 예술과 문화에 스며있다. 하지만 이 말은 고상하게 쓰이는 단어가 아니다. 노동자 계층이 주로 마시던, 거르지 않은 술인 “막걸리”에서 “막”이라는 접두어가 쓰인 것에서 보이듯, 이는 거칠거나 조악한 상태를 주로 의미한다. 어떤 경우에서는 “신경쓰지 않음,” “부주의함” 과 같은 의미도 있지만, 나는 그 핵심을 장식이 없는 상태, 꾸미지 않은, 있는 그대로의 상태를 향한 의지와 같다고 본다. “막”은 장식을 위한 장식을 포함하여, 실질적임과 진솔함을 가로막는 모든 것에 대한 단호한 거절의 제스처이다.

오래전부터 그는 막사발에 깊이 매료되었다. “미국 유학 시절에 잠시 나와 황학 시장에서 정말 좋은 막사발을 만났는데, 이틀 있다가 돈을 가져와서 사겠다고 하고는 미국으로 돌아가게 되어 못 샀어요. 그때 본 막사발의 질감이 아직도 생생해요. 어떻게 생겼는지도 정확하게 기억하고 있죠. 막사발을 들여다보면 도공이 만들다가 어느 순간 중단된 상태의 불완전성이 느껴져요. 결국 그 불완전함을 받아들이는 마음가짐이 막의 미학에 내포되어 있지요.”

양식과 스타일로써 정의되어 온 서양의 미학과 달리 막의 미는 태도, 기질, 정서에 가깝다. 도자기를 만들어 내는 도공의 무심한 마음, 구워진 그릇을 그대로 쓸지 버릴지를 결정하는 기준, 이지러지고 거친 표면을 기꺼이 사용할 수 있는 포용성 같은 것들이 말이다. 한국 미학을 얘기할 때의 미묘한 정서가 여기에 있지 않나 싶기도 하다.

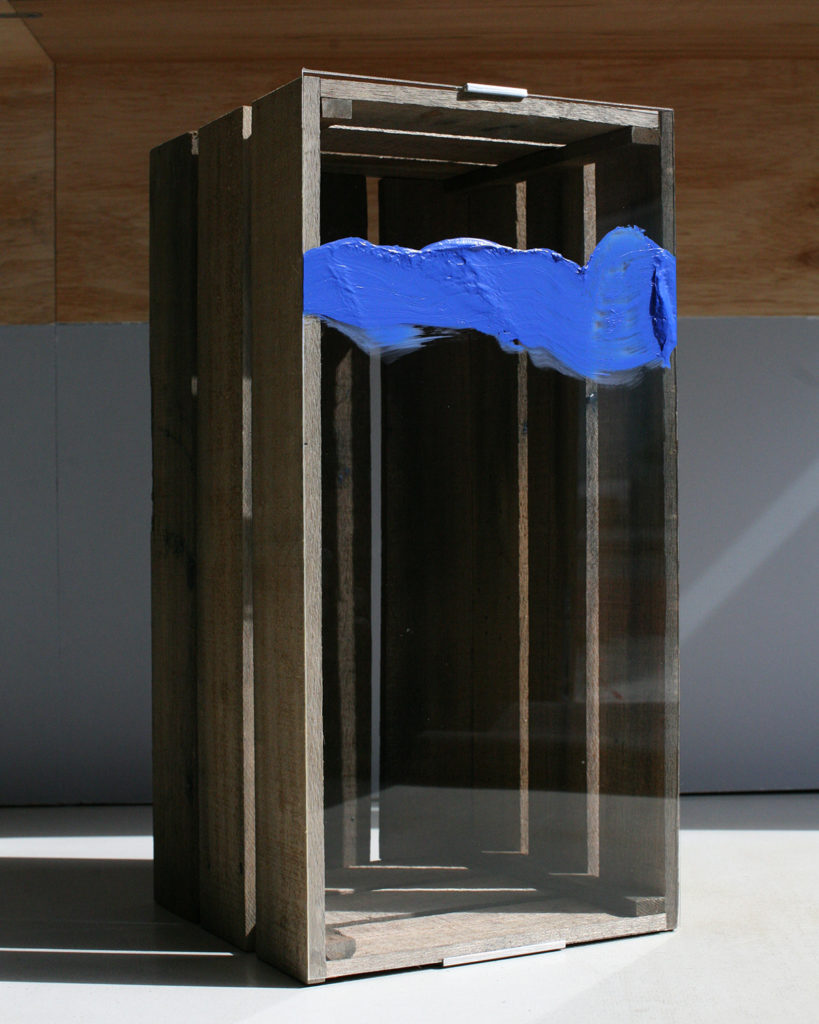

조병수 건축에서는 종종 거칠고 즉흥적인 리듬의 막의 정서가 엿보인다. 불규칙한 배열로 천장과 바닥을 이어주고 있는 열 개의 고목들, 최소한의 형태인 사각 박스의 공간, 벽돌을 잘라 만든 단면, 콘크리트 벽체 사이에 끼워둔 커다란 나무 조각들, 수십 년 전 건물에서 되살린 벽체의 흔적은 꿰매거나 덧붙인 즉흥성의 표현인 동시에 미지의 경험을 향한 그의 소박한 의도였을 것이다.

“온그라운드 카페에도 오래된 벽체에 구멍을 뚫어 놓았는데, 뚫는 과정에서 어디는 덜 깨지고 어디는 더 깨지게 두는 즉흥적인 선택을 했어요. 미음자 집이나 카메라타도 벽체 표면이 다소 거칠게 마무리가 되었잖아요. 옛 것의 흔적을 좋아하는 개인적인 취향 때문일 수도 있는데, 즉흥적으로 마무리되는 거친 미학이 제 건축에서 부분부분 자연스럽게 드러난 것 같아요.”

땅속으로 들어앉은 ‘땅의 건축’ 역시 조병수의 자연적인 미감을 잘 드러내는 것이리라. “제가 대학원 때가 한창 해체주의 건축이 나오고 있었어요. 어떤 형태가 분절된 듯이 날아다니는데, 내가 보기에는 그게 너무 간질간질하고 얄팍하게 다가왔어요. 난 그저 땅을 푹 파놓은 공간이 멋있다고 생각했어요.” 어느 날 공사 중 나무가 뽑혀 만들어진 땅의 움푹한 웅덩이에 들어가 본 그는, 그 속에서 바라보던 하늘과 몸을 따스히 감싸주던 포용의 감각을 아직도 잊지 못한다. ‘대상을 보아 가는 동양화는 화가가 화면에 들어가지 않을 수 없고, 그 안으로 끌려 들어간다’는 고유섭의 표현을 떠올리며, 나의 몸이 닿아 발휘되는 촉각적 경험을 깊이 마주했다.

‘막의 미’라는 화두를 내놓은 그에게 앞으로 어떤 건축을 하고 싶냐고 물었다. “그동안은 늘 올바른 건축을 하려고 애써왔어요. 그런데 앞으로는 좀 더 익사이팅한 걸 해보고 싶어요. 땅과의 관계, 건물의 배치 그리고 건물의 구조나 재료도 솔직하고 담백하게 표현해보고 싶어요. 물론 깨끗한 도자기보다 이렇게 손자국이 묻은 그릇이 더 멋지다는 걸 건축주에게 먼저 설득해야겠지만요.” 잠시 궁금했으나, ‘익사이팅’ 이라는 단어 안에 숨어있을 그의 건축의 가능성을 성급히 가늠해보지 않기로 했다. 그에겐 이미 예견된 건축이, 그 무엇이 존재하고, 그 존재는 자연스럽게 형태를 드러낼 것이기 때문이다.

“

온그라운드 카페에도 오래된 벽체에 구멍을 뚫어 놓았는데, 뚫는 과정에서

어디는 덜 깨지고 어디는 더 깨지게 두는 즉흥적인 선택을 했어요.

When I think of architect Byoungsoo Cho, certain images would arise in my mind before his architecture. Blocks of old wood pieces and stones with cut facets that take up the whole floor of his studio. Along with his charcoal sketches and brushwork drawings spread here and there.

The portfolio of Byoungsoo Cho Architects, which reveals their exploration of materiality and creative urge, was always impressive but not unexpected.

The natural cross between creating art and designing architecture is embodied in his world of architecture. I suppose the chemistry created between the two domains would have trained Cho to build solid architectural muscles.

Whenever I see Cho’s architecture such as the ‘Earth House’ which is set underground, the ‘ㅁ Shaped House’ which is situated on an incline, and ‘Jipyungzip(Horizon House)’ which hides itself low in the horizon, I am reminded of the notions of ‘imperfection, breaking rules, emptiness, understatedness, lack, spontaneity. Perhaps, even long before Cho became an architect, he must have always pondered what Korean beauty is and its essence.

Cho captures the features of Korean beauty from the perspective of ‘aesthetics of mahk(roughness).’ The coincidental display found in Korean traditional architecture. The imperfect nature of mahksabal(meaning roughly-made bowl) derives from the slight shaking of the potter’s hands. The nonchalant airs expressed by a Buddhist monk’s dance. Cho states that we can abbreviate the characteristics of our Korean aesthetics, which consists of stirring up emotional resonance instead of setting a clear format, and the traits of spontaneity or genuineness, all into a one-syllable word ‘mahk’ meaning roughness or crudeness.

The Korean worldview is underlined by a deliberate making of space to improvise; space for spontaneity, the spirit of which I will refer to with the Korean prefix, “mahk”. This spirit permeates the original food, music, writing, dance, and other arts in Korea. But “mahk” is not an elevated term in Korean vernacular. It can infer crudeness or coarseness appearing in the beginning of words such as mahkgulli, an unfiltered rice wine long associated with old school working-class culture. Though in some contexts, it can even go so far as to imply carelessness, at its core, mahk is simply a lack of embellishment, a matter-of-fact departure from the overwrought in general. Mahk is an unapologetic rejection of refinement for the sake of refinement, of ostentation that gets in the way of practicality or honesty.

“

I had made a hole in an old wall again at Onground Café, and during the process

I had made impromptu choices of where I should break less and break more.

He had been deeply drawn to mahksabal early on. “While I was studying in the U.S. I had briefly come back to Korea and went to Hwang-hak market where I encountered a fantastic mahksabal. I told the guy I would come back with the money to buy it two days later, but then I had to return to the U.S. The texture of the bowl that I saw that day is still so vivid in my mind. I remember exactly how it looked. When I look into the bowl, I can feel the incomplete nature rendered by the potter’s spontaneous halt. In the aesthetics of mahk, the mindset of embracing such imperfection is included.”

Contrary to the Western aesthetics defined by form and style, the aesthetics of mahk is closer to a certain attitude, nature, or emotion. The detached state of the potter while making the pottery, the criteria of whether the fired bowl would be used as is or discarded, the generous mind of gladly using the waning bowl with a rough surface, are examples of such. When we talk about Korean aesthetics, I think its peculiar sentiment lies in them.

In Byoungsoo Cho’s architecture, you can often find such sentiment of mahk through its rough and spontaneous rhythm. Ten old wooden pillars connecting the ceiling and the floor in irregular intervals, the cube box space in its minimal form, the cross section of bricks, big wooden pieces inserted into the gaps between concrete walls, the trace of an old wall revived from a decades-old building; they all seem to be expressions of improvisation via sewing up or adding on this and that, which boiled down to his simple intention toward an unknown experience.

“I had made a hole in an old wall again at Onground Café, and during the process I had made impromptu choices of where I should break less and break more. In the ㅁShaped House and Camerata, the wall surface is finished somewhat roughly. It could be due to my personal taste of loving traces of old things, and I guess the coarse aesthetics with impromptu finish had naturally revealed itself here and there in my architecture.”

The ‘Earth House’ which is set inside the ground also displays Cho’s sense of natural beauty. “During my graduate school days, it was the era of deconstruction in architecture. Certain forms were flying about as if cut off from the main structure, but it looked extremely cringeworthy and shallow to me. I just thought a space dug in the ground looked awesome.”

One day on a construction site, a tree was uprooted and left a deep basin in the ground. Cho stepped into this dug-up space and cannot forget the sky he had seen from down there ever since, as well as the sensation of getting a warm hug. While being reminded of the art historian Yuseop Ko’s quote: ‘In oriental painting which follows the subject, the painter cannot refrain from entering inside the canvas, and is totally drawn inside,’ he understood that such a profound encounter with a tactile experience could be essential.

As he had summarized his motto as ‘aesthetics of mahk,’ I asked him what kind of architecture he would like to build in the future. “I had always tried to build good architecture. But from now on, I would like to do something more exciting. The relationship with the ground, the arrangement of buildings, and the structure and material of buildings; I would like to express them in a frank and simple manner. Of course, I would have to first of all persuade the client that a bowl with some finger print marks is more awesome than a clean smooth pottery.” I was briefly curious, but decided not to delve in haste into the potential spectrum of his architecture which would be hidden inside the word ‘exciting.’ Because for him, there is already an architecture or a certain existence foreseen, and such existence would eventually reveal its form in a spontaneous way.

Sunyoung Park 박선영

FREELANCE EDITOR 프리랜스 에디터

RELATED POSTS