죽음에 대해 생각하면 생각나는 몇 가지 것들

What I Think About When I Think About Death

Text by 박상미 Mimi Park

Translation by 김솔하 Solha Kim

나는 가끔 그의 죽음에 ‘자살’이라는 단어를 써야 하나 의문이 들 때가 있다. 그가 물에 뛰어내린 이유가 목숨을 끊기 위해서가 아니라 다른 목적이었고 그 결과가 우연히 죽음이었다면, 이는 사고사로 기록되는 것이 맞지 않을까. 또는 ‘자살’을 소재로 한 퍼모먼스였다면 자신의 괴로운 생을 마감하는 것이 목적이 아니라 자살이라는 것에 대해 생각해보자는 것이 목적이 될 텐데, 그렇다면 그게 자살인가? ‘특정 퍼포먼스로 초래된 체온 저하로 인한 사망’쯤이 되어야 하지 않을까?

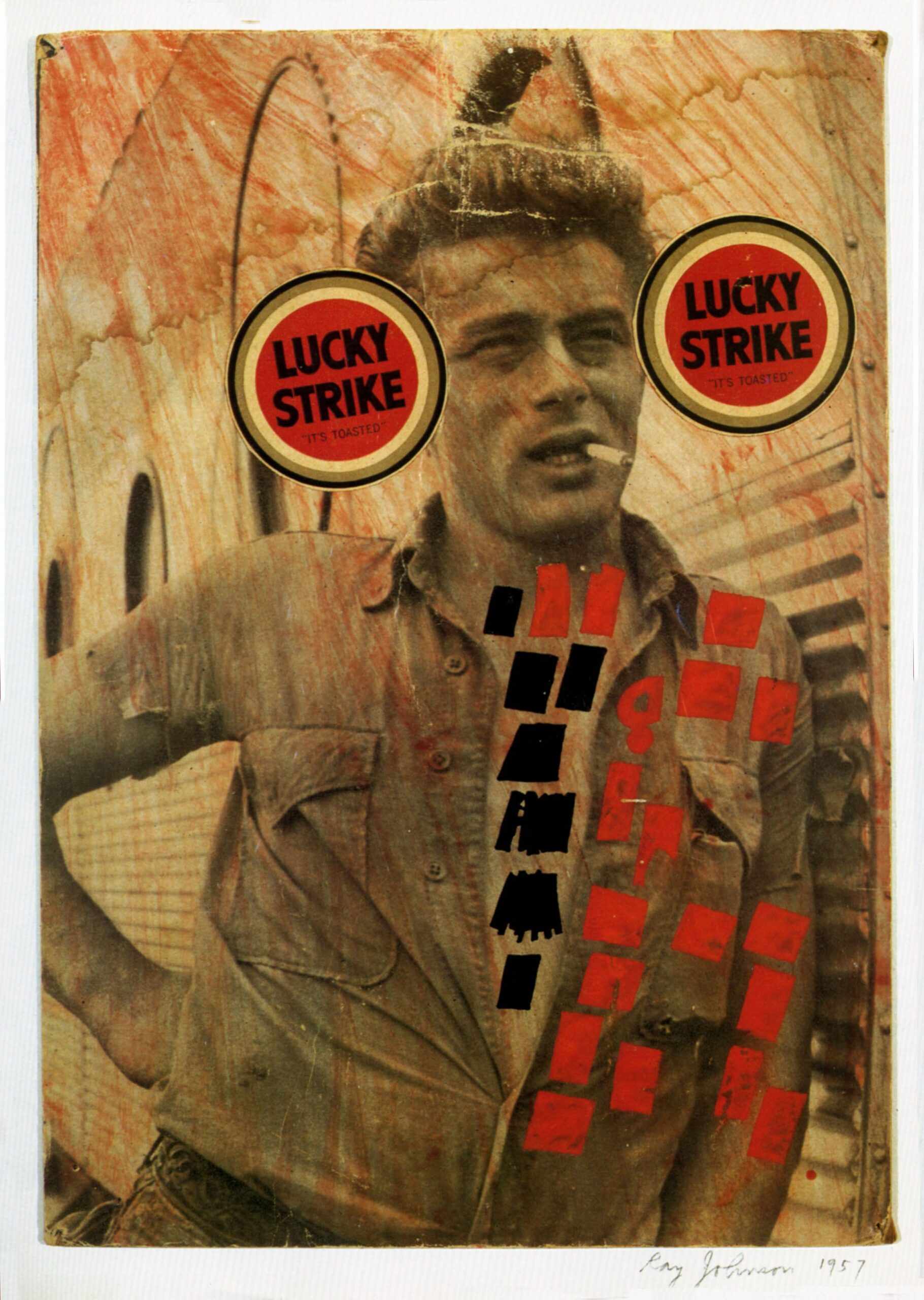

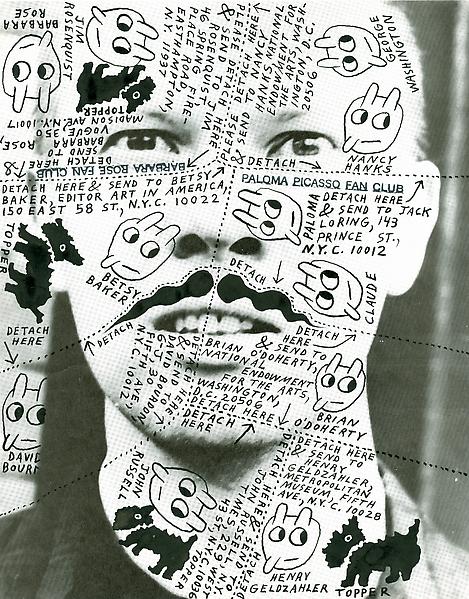

그는 이런 식으로 사람들을 매우 헷갈리게 하는 것이 특기였는데, 한 번은 모트 잰클로우라는 문학 에이전트의 초상 작업을 하겠다고 했다. 그는 잰클로우의 단순한 실루엣을 모티프로 모두 26개의 콜라쥬를 제작하더니, 잰클로우에게 이 작업들을 $42,200에 사라고 했다. 높은 가격에 당황한 잰클로우가 머뭇거리자 그는 절반을 $13,000에 사거나 팔로마 피카소의 초상을 덤으로 줄테니 $18,232에 사라고도 했다. 그는 이런 식으로 작품의 내용과 숫자, 그리고 가격을 계속 바꾸면서 잰클로우에서 계속해서 편지를 보냈다. 이 가격 협상은 결국 이루어지지 않았지만, 그가 서신으로 가격 협상을 한 내용 자체, 이에 반응한 잰클로우라는 인물까지 모두 작업의 내용이 되었다. 초상 작업을 퍼포먼스로 한 것이다. 무대 위가 아닌, 삶 속에 파고든 형태였다.

사람들은 그가 가난하다고 생각했지만, 그가 죽은 후 발견된 그의 지갑에는 모두 $1,600이 있었고, 그의 집과 작업 외에도 은행 구좌에 $400,000이 있었다. 그는 ‘선택적으로 가난’하게 살았고, 돈이 안 되는 작업을 주로 했고, 전시 기획도 하기 힘들었다고 한다. 작품이 돈으로 가치가 매겨지고 매매되는 시스템에 대한 언급이었다. 갤러리에서 전시를 하자고 하면 그는 “I want to do nothing.”이라고 말했다고 한다. 존슨은 ‘해프닝happenings’의 상대적으로 그의 퍼포먼스를 ‘nothings’이라고 불렀기 때문에 갤러리 관계자들은 존슨이 “nothing”이라는 퍼포먼스를 할 건지 아니면 정말로 아무 것도 안 할 건지 알 수가 없었다.

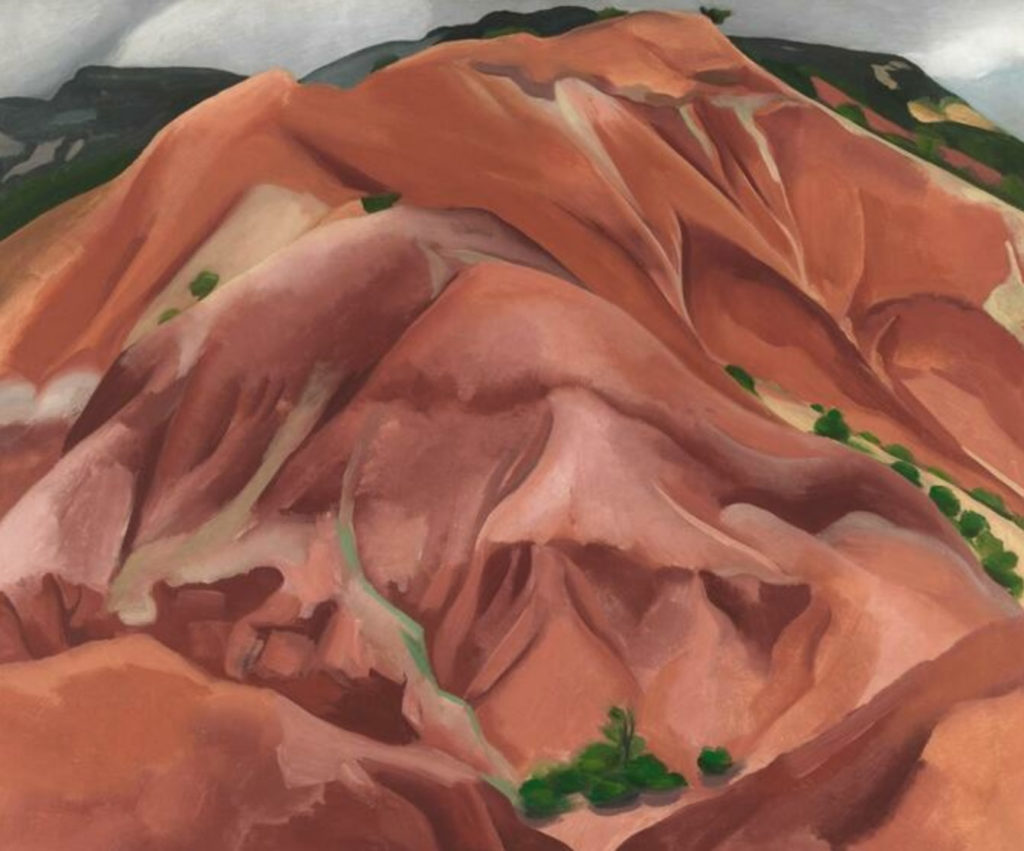

존슨을 알았던 사람들에 따르면 그의 우편물을 받고 영문을 모르던 사람들은 작품을 그냥 버리거나, 또 시간이 지나 잃어버리거나 했다고 한다. 하지만 그의 우편물이, 그의 콜라쥬가 어떤 내용이었는지는 기억하고 있었다. 그의 작품은 비싸게 팔리거나 알려지지 않았지만 많은 사람의 머릿속에 기억으로, 흔적 없이 폭넓게 퍼져있었다. 그의 마지막 작품은 죽음이었고, 사람들은 또 그의 삶 자체가 작품이었다고 말한다. 그와 함께 동양 사상을 공부하고 이야기를 나누었던 윌슨은 그의 죽음에 관해 그의 의식은 마침내 그의 주변과 하나가 되었다고 했다. 그가 정말 바닷물에 몸을 던져 바닷물이라는 거대한 물질 속에 용해되어 하나가 되는 모습을 형상화한 것이라면, 그는 죽음으로써 더욱 살아있게 되었다.

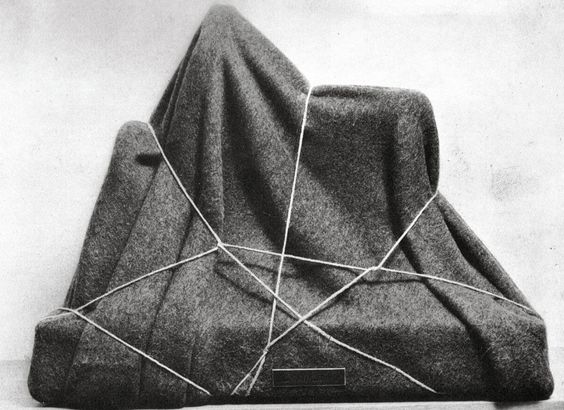

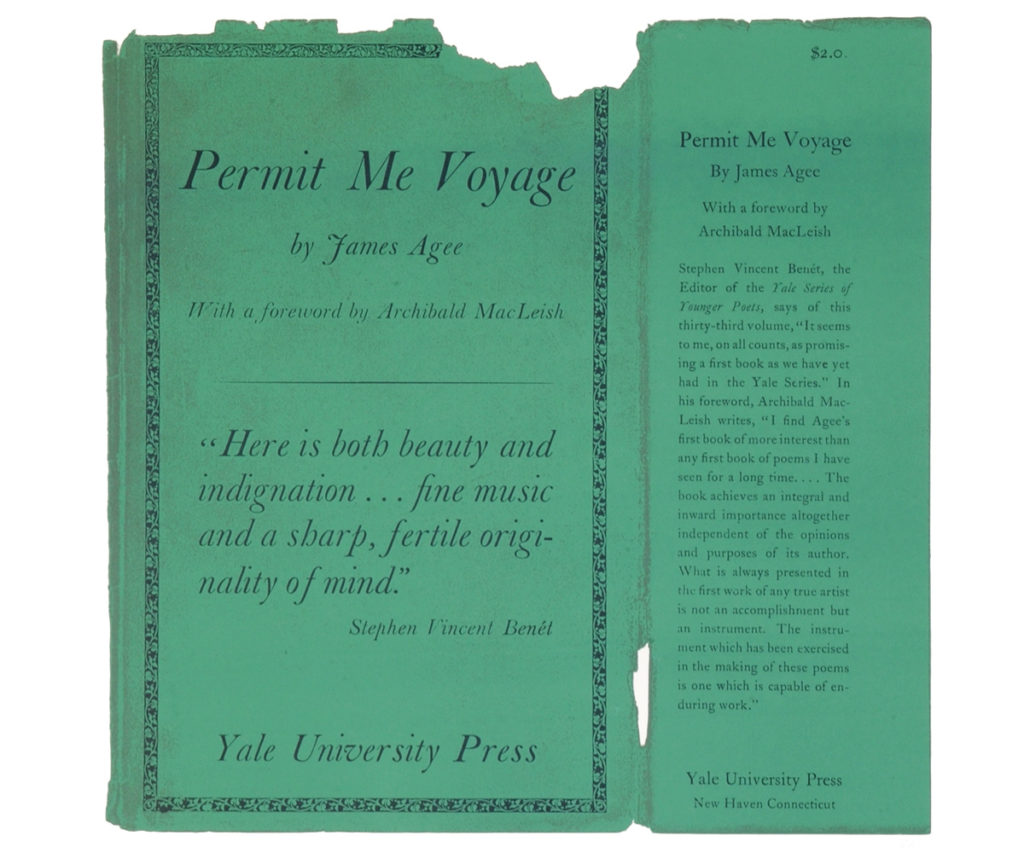

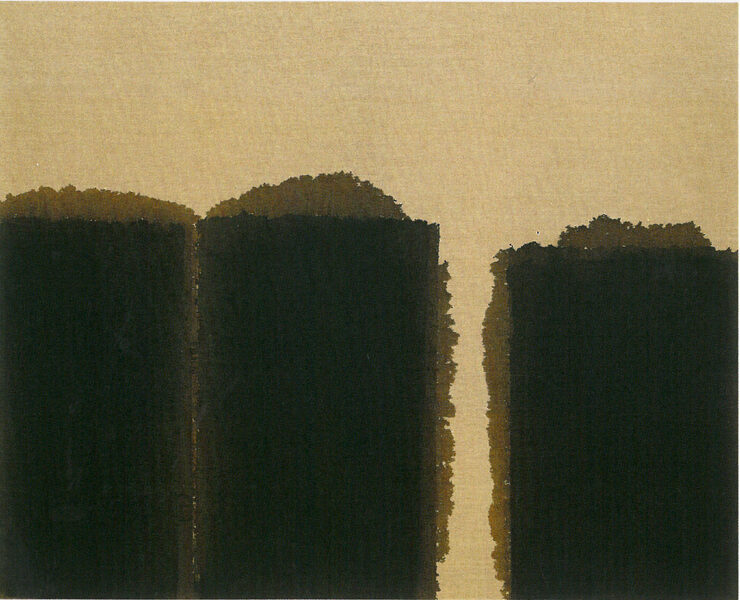

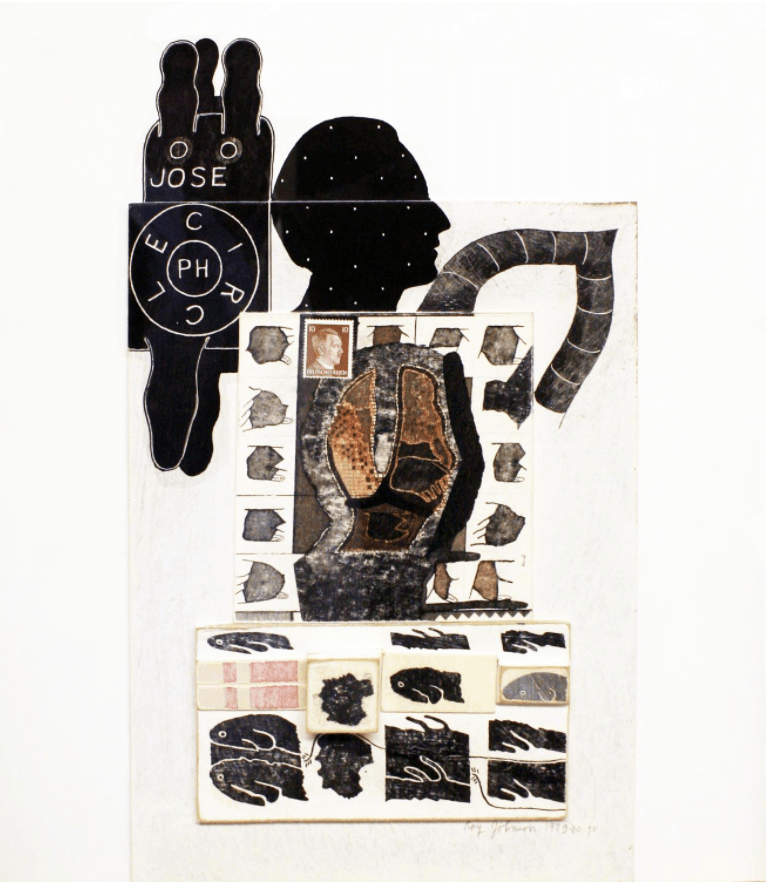

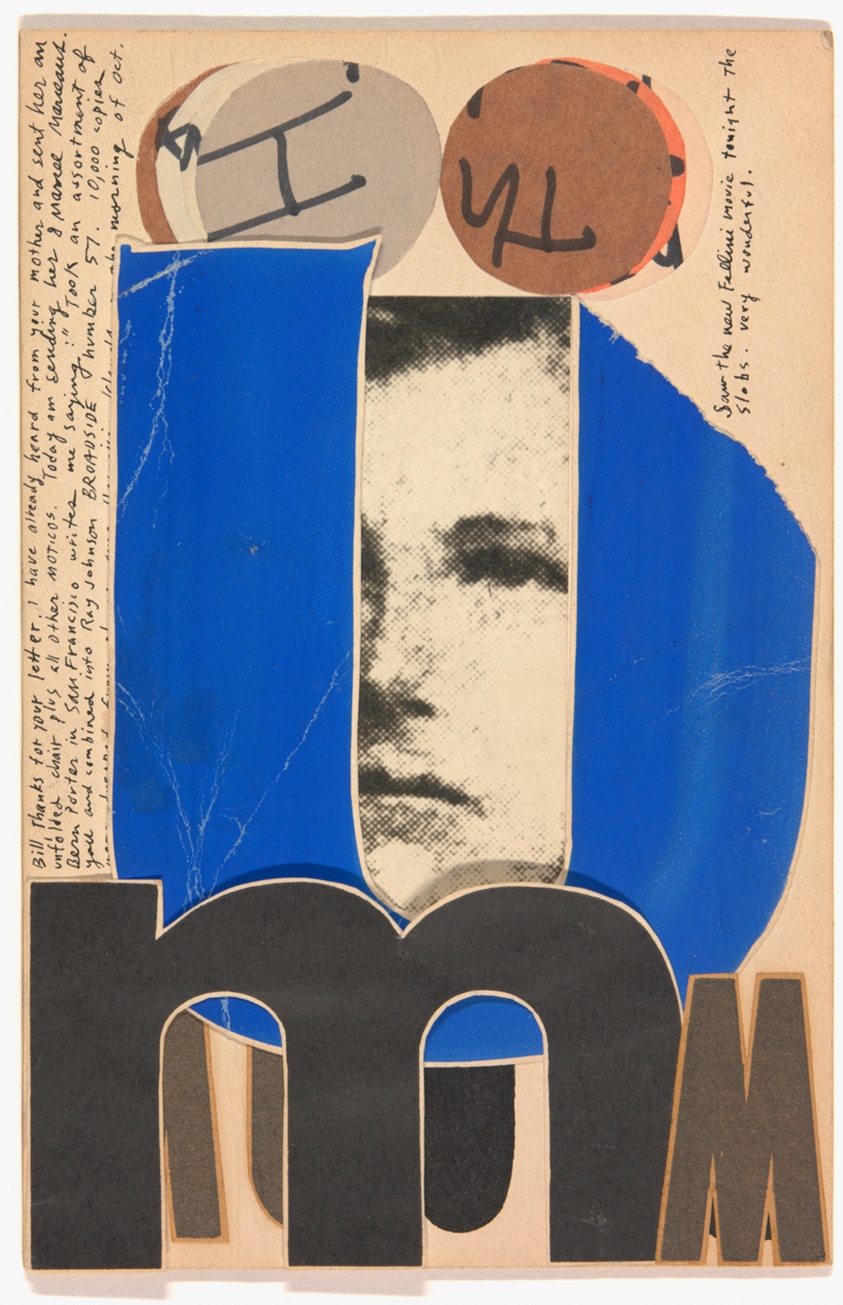

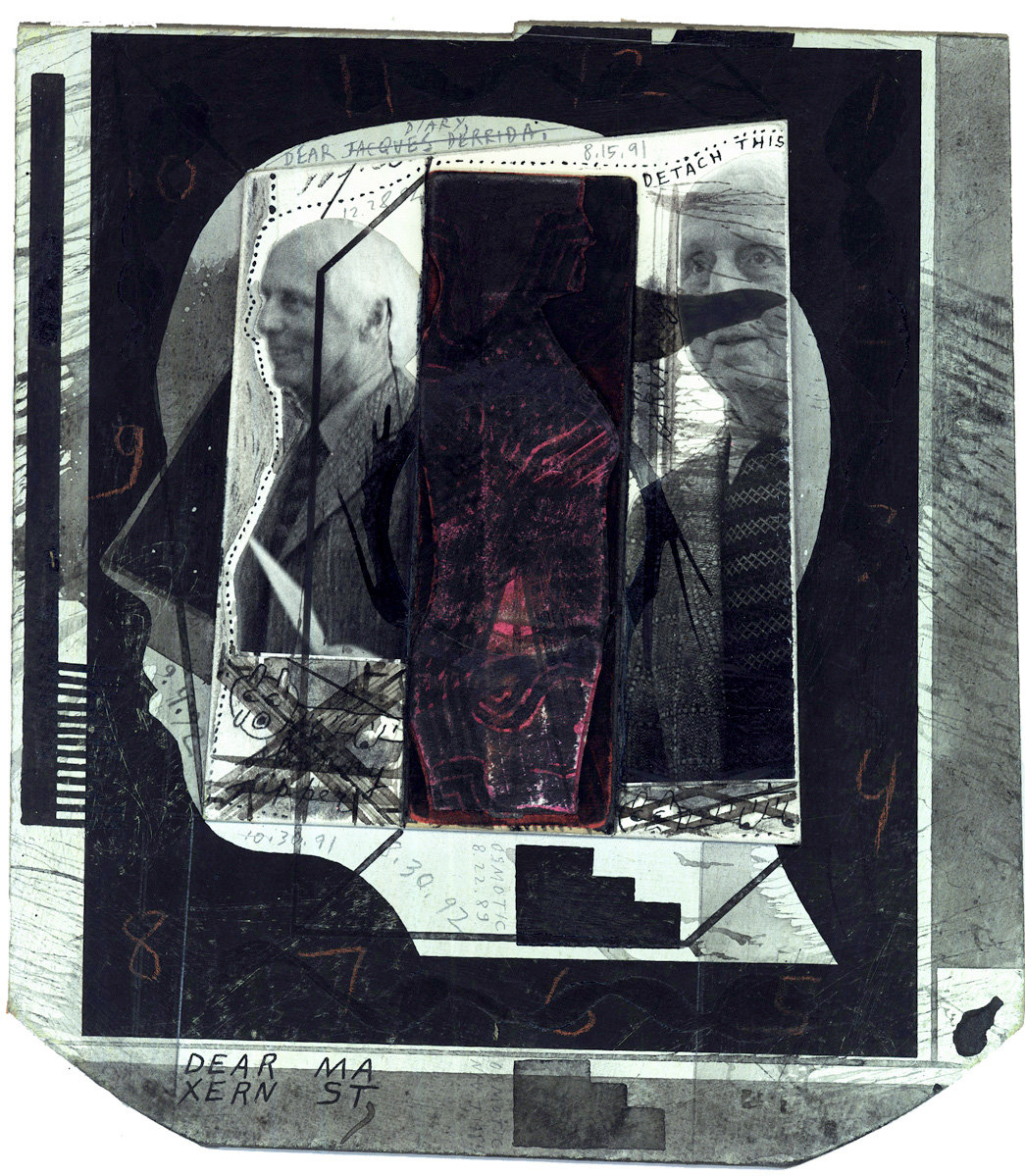

Speaking of someone who would be lying down peacefully in a vast room, Ray Johnson comes to mind. He is one of the artists I think of, upon the theme of death. Ray Johnson is one of the influential figures of Neo-Dada and early Pop art, using celebrity’s image in his work before Andy Warhol did. He mainly made collages, and invented the genre, mail art. He had sent mails almost everyday for nearly 40 years to people in the art world. In New York, there was almost no one who had not received a letter from him when he was alive. He was not known but everybody knew him, and even had his work at one point; his works had permeated into the art world on an unprecedented scale.

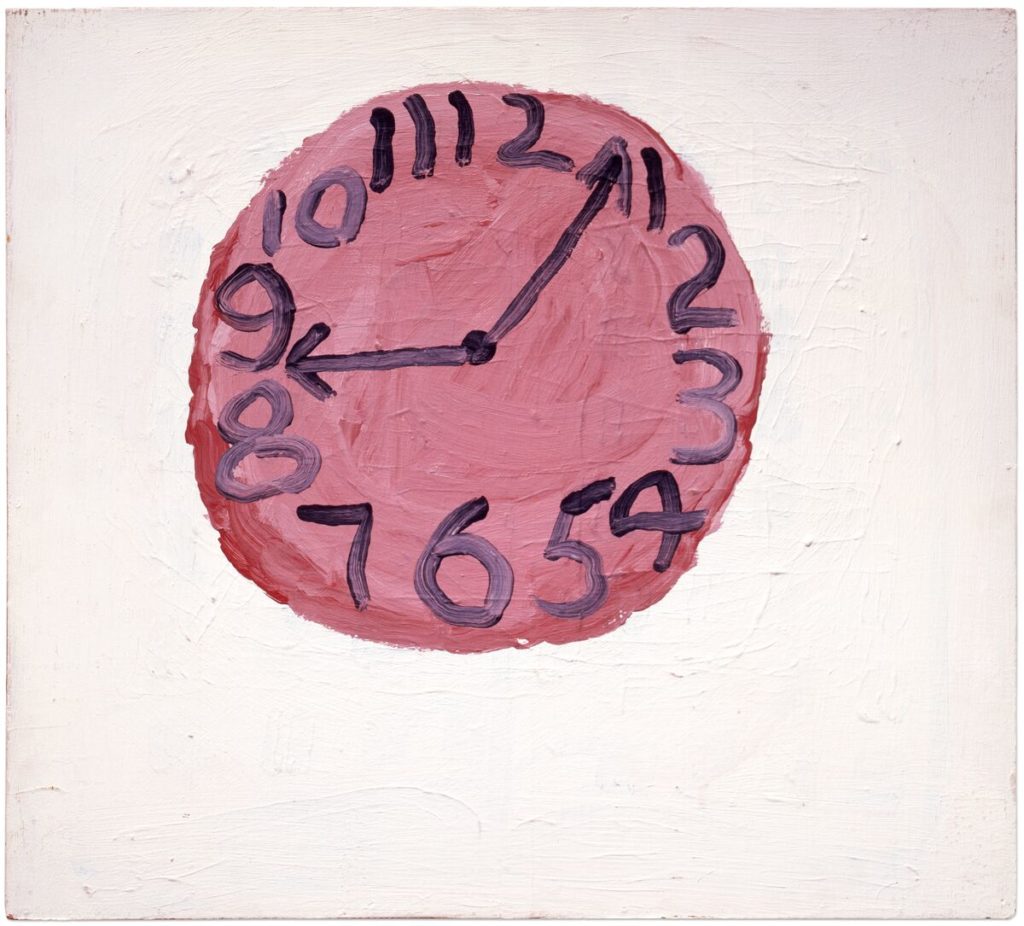

On a cold January morning in 1995, Ray Johnson was found drowned in the sea off Long Island, NY. The day before, which was the 13th, he had stayed at Baron’s Cove Inn near Sag Harbor Cove, at room number 247. (When you add the number of alphabets in the location/motel name, the numbers of the room number, they each sum up to 13.) He checked-in for 90 minutes, and drove his car to the bridge in Sag Harbor. Two teenage girls testified later that they heard a splash of somebody falling in the water at around 7:15. Johnson had called his friend William Wilson (again, 13 letters) a couple of days before and told him that he would soon do a “mail event.” He was 67 years old. (again, 13) Since he did not leave any will, we simply presume his death as suicide. But as if he had been concerned that we didn’t notice it, he made sure that he left clues here and there that his death was a planned event.

I sometimes wonder if we must use the word ‘suicide’ to indicate his death. If the reason he threw himself into the sea was some other objective than breathing his last breath, but the result was a coincidental death, wouldn’t it be correct to record it as an accidental death? And if it was a performance about ‘suicide,’ his motive must have been leading us to think about suicide rather than finishing a painful life, then is this a suicide? Shouldn’t it be called ‘death due to hypothermia which was entailed by a specific performance’?

It was his speciality, indeed, that he could confuse people to the extreme. Once, he proposed to do a portrait of the literary agent Morton Janklow. So he went on creating 26 collages of the motifs based on Janklow’s simple silhouette. Then he proposed to sell the work for $42,200. When the client hesitated at the high price, Johnson offered the half of the work for $13,000 with some other work thrown in or the whole work for $18,232 and he would add the portraits of Paloma Picasso. And he didn’t stop there. He would continuously change the content, number, and price of the work and kept on sending letters to Janklow. The price negotiation never came to a successful ending, but the correspondence of the whole negotiation process, the subject of the portrait himself became all part of the work. Johnson turned a portrait consignment into a performance piece. A performance not held on stage, but immersed in life.

People thought he was poor, but the wallet found after his death contained $1,600, and he also had his house, his art work, and a sum of $400,000 in his savings. He lived in poverty by choice, while mostly creating pieces that could not sell, and was being extremely difficult in talking about future exhibitions. When a gallery would propose an exhibition, he would answer “I want to do nothing.” He called his performances ‘nothings’ as opposed to ‘happenings,’ so the gallery people could never be quite sure whether he would do a performance titled ‘nothing’ or he would actually do nothing. How he lived and behaved was his statement on the system of art works being valued monetarily and sold.

According to a friend who knew Johnson, people who received his post and not exactly knowing what he was doing, would just throw them away, or simply lose it with time. But they could all remember what his mailed collages looked like or what they said. He widely pervaded many people’s minds, as a memory without physical trace. His last piece was his death, and people consider his life itself to be his work. Wilson, who Johnson called before his death, studied and conversed about Eastern thoughts and philosophies with him when they were young, and said that his ritual of death signifies he had become one at last with his surroundings. If he had truly visualized the image of becoming one with the sea by throwing himself into the water and being dissolved, he has become more alive with this death.

RELATED POSTS